Daniel Defoe and the Great North Road

Amongst many other things, Daniel Defoe was an early travel writer who immersed himself in his subject and wrote with descriptive detail about what he saw. Most of the towns and cities along the Great North Road are recorded by Daniel Defoe. His “Tour thro’ the whole island of Great Britain” was based on lengthy journeys he made in the early 1720s, zig-zagging the length and breadth of the country. He provides a unique snapshot of people, trade, finance, transport, politics and religion. Britain is still an agricultural economy but the towns are growing, new international trade routes are being established, impressive country estates are appearing, and there is a keen interest in science and technology – the Age of Enlightenment is in full swing and Industrial Revolution is not far off.

The Tour was published as a series of 13 letters relating to several Circuits or Journeys. The author is keen to note that his observations are based on his personal travels – though it is likely that for some sections he relied on recollections from visits earlier in his career.

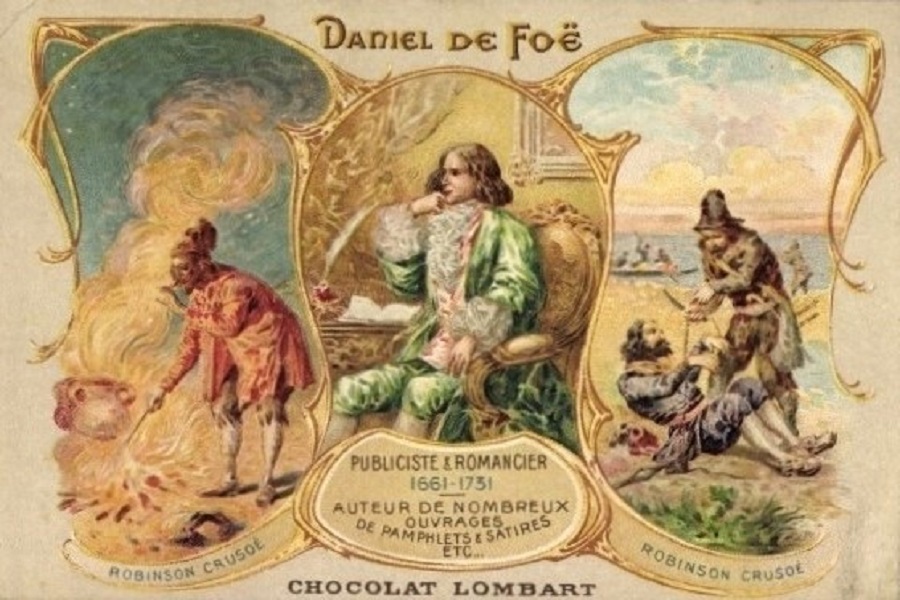

About Daniel Defoe

Born in a bout 1660, Defoe was a great observer, listener and communicator. He was a driven, hardworking, principled man, but not averse to risk taking and “projecting” to improve his own economic and social position. At times his trading activities generated significant wealth, he married into a prosperous family and he added the “De” to his name of Foe for effect.

At other times it seems he lost focus on his businesses, and his religious and political battles came to the fore. He was more than once imprisoned – the first time in the early 1690s following bankruptcy.

He was responsible for several political pamphlets which were the widely read newspapers or blogs of the day.

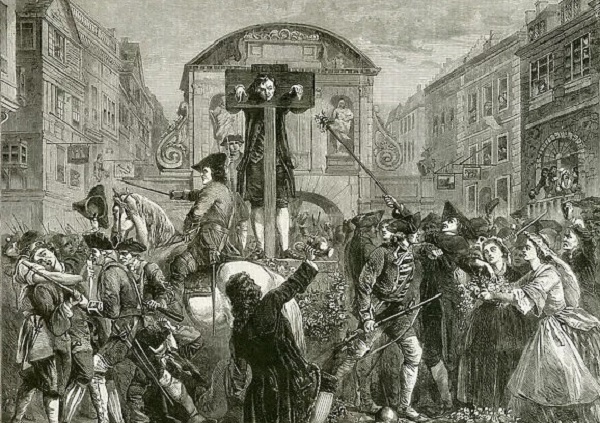

As a result of a controversial pamphlet attacking the High Church, Defoe was found guilty of seditious libel in 1703 resulting in 3 days in the pillory before being sent to Newgate Prison.

In the early 1700s his political associations paid great dividends, not least when he was employed by the crown as an undercover agent in Scotland. In support of the Act of Union he reported on key players and generated favourable media articles.

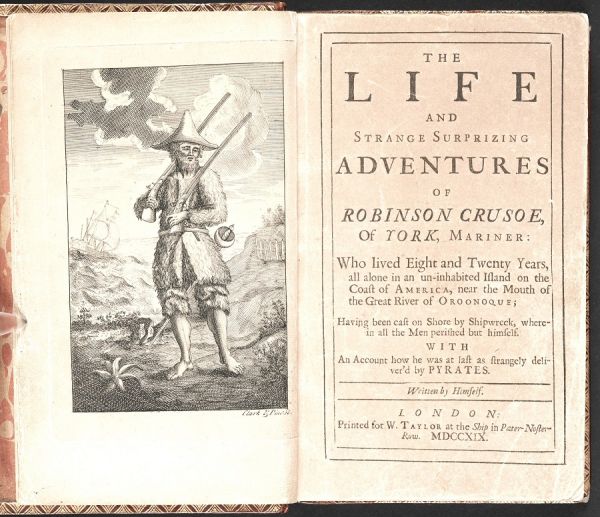

When business and political opportunities faded he took to writing books. Fictional works such as Robinson Crusoe, Moll Flanders and Roxana are often cited as being amongst the first ever novels. His ability to tell gripping and detailed stories, often related by the central figure themselves, suggests they had perhaps been told many times before in coffee houses, taverns, inns and around dinner tables.

The Life and Strange Surprizing Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner, 1719

He maintained his journalistic skills with the Tour Through The Whole Island of Great Britain. And he also wrote self-help books including The Complete English Tradesman. Ironically, a regular theme was the need for financial prudence and methodical bookkeeping. He was pursued by creditors to the last and was buried in a pauper’s grave in 1731.

From London to Edinburgh with Daniel Defoe

The extracts below are snippets about places along the Great North Road, coupled with broadly contemporary images. To provide a logical sequence from London to Edinburgh they are not in the same order as they appear in the original publication.

Defoe was respectful of William Camden, the early antiquarian, who in his Britannia provided many well researched historical records and insights. Defoe’s focus was on buildings, physical infrastructure, agriculture and business.

I am writing a description of places, not of persons, giving the present state of things, not their history: And therefore, though in some cases I may step back into history, yet, it shall be very seldom, and on extraordinary occasions.

Ogilby’s Britannia of 1675 might be useful as a contemporary route map.

London

There is a lengthy commentary on London including detail on its dimensions and the new buildings and squares completed following the Great Fire of 1666; the splendour (and missed opportunities) of St Paul’s; the improved supply of water; the rebuilding of the great gates; and the need to upgrade the royal palace. We will focus on a few general reflections and the sections relating to the route north from the city.

The Northwest Prospect of Saint Paul’s Cathedral, 1720, AD Puller

Letter 5

London, as a city only, and as its walls and liberties line it out, might, indeed, be viewed in a small compass; but, when I speak of London, now in the modern acceptation, you expect I shall take in all that vast mass of buildings, reaching from Black-Wall in the east, to Tot-Hill Fields in the west; and extended in an unequal breadth, from the bridge, or river, in the south, to Islington north; and from Peterburgh House on the bank side in Westminster, to Cavendish Square, and all the new buildings by, and beyond, Hannover Square, by which the city of London, for so it is still to be called, is extended to Hide Park Corner in the Brentford Road, and almost to Maribone in the Acton Road, and how much farther it may spread, who knows? New squares, and new streets rising up every day to such a prodigy of buildings, that nothing in the world does, or ever did, equal it, except old Rome in Trajan’s time, when the walls were fifty miles in compass, and the number of inhabitants six million eight hundred thousand souls.

It is the disaster of London, as to the beauty of its figure, that it is thus stretched out in buildings, just at the pleasure of every builder, or undertaker of buildings, and as the convenience of the people directs, whether for trade, or otherwise; and this has spread the face of it in a most straggling, confus’d manner, out of all shape, uncompact, and unequal; neither long or broad, round or square; whereas the city of Rome, though a monster for its greatness, yet was, in a manner, round, with very few irregularities in its shape.

At London, including the buildings on both sides the water, one sees it, in some places, three miles broad, as from St. George’s in Southwark, to Shoreditch in Middlesex; or two miles, as from Peterburgh House to Montague House; and in some places, not half a mile, as in Wapping; and much less, as in Redrirf.

We see several villages, formerly standing, as it were, in the country, and at a great distance, now joyn’d to the streets by continued buildings, and more making haste to meet in the like manner; for example, Deptford, This town was formerly reckoned, at least two miles off from Redriff, and that over the marshes too, a place unlikely ever to be inhabited; and yet now, by the encrease of buildings in that town itself, and the many streets erected at Redriff, and by the docks and building-yards on the river side, which stand between both, the town of Deptford, and the streets of Redriff, or Rotherhith (as they write it) are effectually joyn’d, and the buildings daily increasing; so that Deptford is no more a separated town, but is become a part of the great mass, and infinitely full of people also; Here they have, within the last two or three years, built a fine new church, and were the town of Deptford now separated, and rated by itself, I believe it contains more people, and stands upon more ground, than the city of Wells.

The town of Islington, on the north side of the city, is in like manner joyn’d to the streets of London, excepting one small field, and which is in itself so small, that there is no doubt, but in a very few years, they will be intirely joyn’d, and the same may be said of Mile-End, on the east end of the town.

Newington, Tottenham, Edmonton, and Enfield stand all in a line N. from the city; the encrease of buildings is so great in them all, that they seem to a traveller to be one continu’d street; especially Tottenham and Edmonton, and in them all, the new buildings so far exceed the old, especially in the value of them, and figure of the inhabitants, that the fashion of the towns are quite altered.

At Tottenham we see the remains of an antient building called the Cross, from which the town takes the name of High-Cross. There is a long account of the antiquities of this place lately published, to which I refer, antiquities as I have observed, not being my province in this work, but a description of things in their present state.

Tottenham High Cross was erected in the early 17th century on the site of a wooden wayside cross

Here is at this town a small but pleasant seat of the Earl of Colerain, in Ireland; his lordship is now on his travels, but has a very good estate here extending from this town to Muzzle-hill, and almost to High-gate.

The first thing we see in Tottenham is a small but beautiful house, built by one Mr. Wanly, formerly a goldsmith, near Temple Bar; it is a small house, but for the beauty of the building and the gardens, it is not outdone by any of the houses on this side the country.

There is not any thing more fine in their degree, than most of the buildings this way; only with this observation, that they are generally belonging to the middle sort of mankind, grown wealthy by trade, and who still taste of London; some of them live both in the city, and in the country at the same time: yet many of these are immensely rich.

Hampstead indeed is risen from a little country village, to a city, not upon the credit only of the [mineral] waters, tho’ ’tis apparent, its growing greatness began there; but company increasing gradually, and the people liking both the place and the diversions together; it grew suddenly populous, and the concourse of people was incredible. This consequently raised the rate of lodgings, and that encreased buildings, till the town grew up from a little village, to a magnitude equal to some cities; nor could the uneven surface, inconvenient for building, uncompact, and unpleasant, check the humour of the town, for even on the very steep of the hill, where there’s no walking twenty yards together, without tugging up a hill, or stradling down a hill, yet ’tis all one, the buildings encreased to that degree, that the town almost spreads the whole side of the hill.

Early 18th century townhouses in Hampstead

A topic which excites Defoe in the context of London is the emergence of an effective postal system, accelerating communication within and beyond the city.

The Post Office, a branch of the revenue formerly not much valued, but now, by the additional penny upon the letters, and by the visible increase of business in the nation, is grown very considerable.

The penny post, a modern contrivance of a private person, one Mr. William Dockraw, is now made a branch of the general revenue by the Post Office; and though, for a time, it was subject to miscarriages and mistakes, yet now it is come also into so exquisite a management, that nothing can be more exact, and ’tis with the utmost safety and dispatch, that letters are delivered at the remotest corners of the town, almost as soon as they could be sent by a messenger, and that from four, five, six, to eight times a day, according as the distance of the place makes it practicable; and you may send a letter from Ratcliff or Limehouse in the East, to the farthest part of Westminster for a penny, and that several times in the same day.

Nor are you tied up to a single piece of paper, as in the General Post-Office, but any packet under a pound weight, goes at the same price.

Letter sent from London to West Drayton, 1694

I mention this the more particularly, because it is so manifest a testimony to the greatness of this city, and to the great extent of business and commerce in it, that this penny conveyance should raise so many thousand pounds in a year, and employ so many poor people in the diligence of it, as this office employs.

We see nothing of this at Paris, at Amsterdam, at Hamburgh, or any other city, that ever I have seen, or heard of.

Hertfordshire & Bedfordshire

Defoe always has an eye for trade as is seen here in his notes on the towns of north Hertfordshire and Bedfordshire.

Letter 7

But leaving these undertakings to speak for themselves when finish’d; for they can neither be justly prais’d or censur’d before; it ought to be observ’d, that there is another road branching out from this deep way at Stevenage, and goes thence to Hitchin, to Shefford, and Bedford. Hitchin is a large market town, and particularly eminent for its being a great corn market for wheat and malt, but especially the first, which is bought here for London market. The road to Hitchin, and thence to Bedford, tho’ not a great thorough-fare for travellers, yet is a very useful highway for the multitude of carriages, which bring wheat from Bedford to that market, and from the country round it, even as far as Northamptonshire, and the edge of Leicestershire; and many times the country people are not able to bring their corn for the meer badness of the ways.

The former Stevenage malthouse and kiln from 17th century (or earlier)

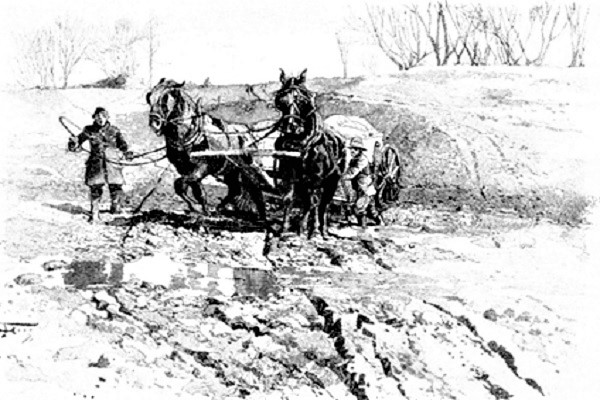

Another theme for Daniel Defoe was the poor state of many roads. He compares them unfavourably to the old Roman highways and argues that they are holding back economic growth. He is hopeful that there will be significant improvement as a result of the turnpikes which are starting to appear. He particularly notes the clay soils north of the Chilterns which impede efficient transport between London and its hinterland.

Appendix to Volume 2

That the soil of all the midland part of England, even from sea to sea, is of a deep stiff clay, or marly kind, and it carries a breadth of near 50 miles at least, in some places much more; ?or is it possible to go from London to any part of Britain, north, without crossing this clayey dirty part. For example;

Suppose we take the great northern post road from London to York, and so into Scotland; you have tolerable good ways and hard ground, ’till you reach Royston about 32, and to Kneesworth, a mile farther: But from thence you enter upon the clays, which beginning at the famous Arrington-Lanes, and going on to Caxton, Huntington, Stilton, Stamford, Grantham, Newark, Tuxford (call’d for its deepness Tuxford in the Clays) holds on ’till we come almost to Bautree, which is the first town in Yorkshire, and there the country is hard and sound, being part of Sherwood Forest.

The reason of my taking notice of this badness of the roads, through all the midland counties, is this; that as these are counties which drive a very great trade with the city of London, and with one another, perhaps the greatest of any counties in England; and that, by consequence, the carriage is exceeding great, and also that all the land carriage of the northern counties necessarily goes through these counties, so the roads had been plow’d so deep, and materials have been in some places so difficult to be had for repair of the roads, that all the surveyors rates have been able to do nothing; nay, the very whole country has not been able to repair them; that is to say, it was a burthen too great for the poor farmers; for in England it is the tenant, not the landlord, that pays the surveyors of the highways.

This necessarily brought the country to bring these things before the Parliament; and the consequence has been, that turnpikes or toll-bars have been set up on the several great roads of England, beginning at London, and proceeding thro’ almost all those dirty deep roads, in the midland counties especially; at which turn-pikes all carriages, droves of cattle, and travellers on horseback, are oblig’d to pay an easy toll

There is another road, which is a branch of the northern road, and is properly called the coach road, and which comes into the other near Stangate Hole; and this indeed is a most frightful way, if we take it from Hatfield, or rather the park corners of Hatfield House, and from thence to Stevenage, to Baldock, to Biggleswade, and Bugden. Here is that famous lane call’d Baldock Lane, famous for being so unpassable, that the coaches and travellers were oblig’d to break out of the way even by force, which the people of the country not able to prevent, at length placed gates, and laid their lands open, setting men at the gates to take a voluntary toll, which travellers always chose to pay, rather than plunge into sloughs and holes, which no horse could wade through.

This terrible road is now under cure by the same methods, and probably may in time be brought to be firm and solid, the chalk and stones being not so far to fetch here, as in some of those other places I have just now mention’d.

But the repair of the roads in this county, namely Bedfordshire, is not so easy a work, as in some other parts of England. The drifts of cattle, which come this way out of Lincolnshire and the fens of the Isle of Ely, of which I have spoken already, are so great, and so constantly coming up to London markets, that it is much more difficult to make the ways good, where they are continually treading by the feet of the large heavy bullocks, of which the numbers that come this way are scarce to be reckon’d up, and which make deep impressions, where the ground is not very firm, and often work through in the winter what the commissioners have mended in the summer.

Stilton – Huntingdon

Defoe is travelling south from Stilton to Huntingdon as he rounds off a tour of the Midlands.

Letter 7

Coming south from hence we pass’d Stilton, a town famous for cheese, which is call’d our English Parmesan, and is brought to table with the mites, or maggots round it, so thick, that they bring a spoon with them for you to eat the mites with, as you do the cheese.

Hence we came through Sautrey Lane, a deep descent between two hills, in which is Stangate Hole, famous for being the most noted robbing-place in all this part of the country. Hence we pass’d to Huntington, the county town, otherwise not considerable; it is full of very good inns, is a strong pass upon the Ouse, and in the late times of rebellion it was esteemed so by both parties.

Here are the most beautiful meadows on the banks of the River Ouse, that I think are to be seen in any part of England; and to see them in the summer season, cover’d with such innumerable stocks of cattle and sheep, is one of the most agreeable sights of its kind in the world.

Peterborough

Defoe references Peterborough and its environs both in the context of its connections to the productive fenland, and as an historic location on the routes dating back to the Romans.

Letter 7

Whittlesea and Ramsey meres are two lakes, made by the River Nyne or Nene, which runs through them; the first is between five and six miles long, and three or four miles broad, and is indeed full of excellent fish for this trade.

Here is a particular trade carry’d on with London, which is no where else practis’d in the whole kingdom, that I have met with, or heard of, (viz.) For carrying fish alive by land-carriage; this they do by carrying great buts fill’d with water in waggons, as the carriers draw other goods: The buts have a little square flap, instead of a bung, about ten, twelve, or fourteen inches square, which, being open’d, gives air to the fish, and every night, when they come to the inn, they draw off the water, and let more fresh and sweet water run into them again. In these carriages they chiefly carry tench and pike, pearch and eels, but especially tench and pike, of which here are some of the largest in England.

There are more of these [Duckoys or Decoys] about Peterbro’ who send the fowl up twice a week in waggon loads at a time, whose waggons before the late Act of Parliament to regulate carriers, I have seen drawn by ten, and twelve horses a piece, they were loaden so heavy.

Entrance to Duck Decoy Pipe, Miller Christie

From the Fenns, longing to be deliver’d from fogs and stagnate air, and the water of the colour of brew’d ale, like the rivers of the Peak, we first set foot on dry land, as I call’d it, at Peterborough.

This is a little city, and indeed ’tis the least in England; for Bath, or Wells, or Ely, or Carlisle, which are all call’d cities, are yet much bigger; yet Peterborough is no contemptible place neither; there are some good houses in it, and the streets are fair and well-built; but the glory of Peterborough is the cathedral, which is truly fine and beautiful; the building appears to be more modern, than the story of the raising this pile implies, and it wants only a fine tower steeple, and a spire on the top of it, as St. Paul’s at London had, or as Salisbury still has; I say, it wants this only to make it the finest cathedral in Britain, except St. Paul’s, which is quite new, and the church of St. Peter at York.

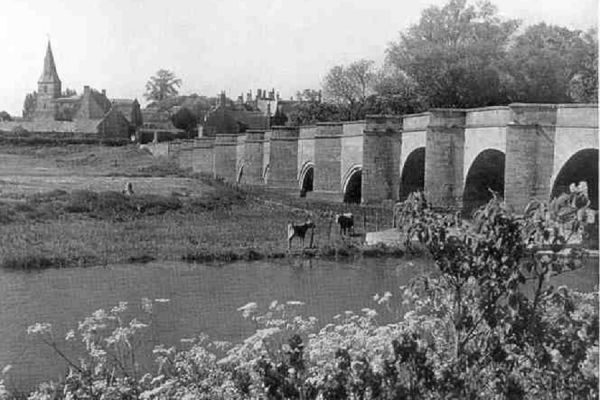

Near this little village of Castor lives the Lord FitzWilliams, of an ancient family, tho’ an Irish title, and his lordship has lately built a very fine stone bridge over the River Nyne, near Gunworth, where formerly was the ferry.

I was very much applauding this generous action of my lord’s, knowing the inconvenience of the passage there before, especially if the waters of the Nyne were but a little swell’d, and I thought it a piece of publick charity; but my applause was much abated, when coming to pass the bridge (being in a coach) we could not be allow’d to go over it, without paying 2s. 6d. of which I shall only say this, That I think ’tis the only half crown toll that is in Britain, at least that ever I met with.

By the park wall, or, as some think, through the park, adjoining to Burleigh House, pass’d an old Roman highway, beginning at Castor, a little village near Peterborough; but which was anciently a Roman station, or colony, call’d Durobrevum; this way is still to be seen, and is now call’d The 40 Foot Way, passing from Gunworth Ferry (and Peterborough) to Stamford: This was, as the antiquaries are of opinion, the great road into the north, which is since turn’d from Stilton in Huntingdonshire to Wandsworth or Wandsford, where there is a very good bridge over the River Nyne; which coming down from Northampton, as I have observ’d already, passes thence by Peterborough, and so into the Fen country: But if I may straggle a little into antiquity, (which I have studiously avoided) I am of opinion, neither this or Wandsford was the ancient northern road in use by the Romans; for ’tis evident, that the great Roman causway is still seen on the left hand of that road, and passing the Nyne at a place call’d Water Neuton, went directly to Stamford, and pass’d the Welland, just above that town, not in the place where the bridge stands now; and this Roman way is still to be seen, both on the south and the north side of the Welland, stretching itself on to Brig Casterton, a little town upon the River Guash, about three miles beyond Stamford; which was, as all writers agree, another Roman station, and was call’d Guasennæ by the antients, from whence the river is supposed also to take its name; whence it went on to Panton, another very considerable colony, and so to Newark, where it cross’d the Foss.

Additional arches were added to the 16th century bridge over the Nene at Wansford in the 1780s

Stamford

Letter 7

There is a very fine stone bridge over the River Welland of five arches, and the town-hall is in the upper part of the gate, upon or at the end of the bridge, which is a very handsome building. There are two constant weekly markets here, viz. on Mondays and Fridays, but the last is the chief market: They have also three fairs, viz. St. Simon and Jude, St. James’s, and Green-goose Fair, and a great Midlent mart; but the latter is not now so considerable, as it is reported to have formerly been.

A stylised view of Stamford from the south by Samuel and Nathaniel Buck, 1743

But the beauty of Stamford is the neighbourhood of the noble palace of the Earl of Excester, call’d Burleigh House, built by the famous Sir William Cecil, Lord Burleigh, and Lord High Treasurer to Queen Elizabeth, the same whose monument I just now mentioned, being in St. Martin’s Church at Stamford-Baron, just without the park.

This house, built all of free-stone, looks more like a town than a house, at which avenue soever you come to it; the towers and the pinnacles so high, and placed at such a distance from one another, look like so many distant parish-churches in a great town, and a large spire cover’d with lead, over the great clock in the center, looks like the cathedral, or chief church of the town.

The house stands on an eminence, which rises from the north en trance of the park, coming from Stamford: On the other side, viz. south and west, the country lies on a level with the house, and is a fine plain, with posts and other marks for horse-races; As the entrance looks towards the flat low grounds of Lincolnshire, it gives the house a most extraordinary prospect into the Fens, so that you may see from thence twenty or near thirty miles, without any thing to intercept the sight.

Grantham

Letter 7

From hence we came to Grantham, famous for a very fine church and spire steeple, so finely built, and so very high, that I do not know many higher and finer built in Britain. The vulgar opinion, that this steeple stands leaning, is certainly a vulgar error: I had no instrument indeed to judge it by, but, according to the strictest observation, I could not perceive it, or anything like it, and am much of opinion with that excellent poet:

‘Tis hight makes Grantham steeple stand awry. This is a neat, pleasant, well-built and populous town, has a good market, and the inhabitants are said to have a very good trade, and are generally rich. There is also a very good free-school here. This town lying on the great northern road is famous, as well as Stamford, for abundance of very good inns, some of them fit to entertain persons of the greatest quality and their retinues, and it is a great advantage to the place.

St Wulfram’s Church, Grantham (Drawn by W. Turner in 1797 from a sketch by Schenebbelie)

From a hill, about a mile beyond this town north west, being on the great York road, we had a prospect again into the Vale of Bever, or Belvoir, which I mentioned before; and which spreads itself here into 3 counties, to wit, Lincoln, Leicester, and Rutlandshires: also here we had a distant view of Bever, or Bellevoir Castle, which ’tis supposed took its name from the situation, from whence there is so fine a prospect, or Bellevoir over the country; so that you see from the hill into six counties, namely, into Lincoln, Nottingham, Darby, Leicester, Rutland, and Northampton Shires.

View of Belvoir Castle, Jan the Younger Griffier, 1744

Newark

Letter 7

At Newark one can hardly see without regret the ruins of that famous castle, which maintain’d itself through the whole Civil War in England, and keeping a strong garrison there for the king to the last, cut off the greatest pass into the north that is in the whole kingdom; ?or was it ever taken, ’till the king, press’d by the calamity of his affairs, put himself into the hands of the Scots army, which lay before it, and then commanded the governor to deliver it up, after which it was demolish’d, that the great road might lye open and free; and it remains in rubbish to this day. Newark is a very handsome well-built town, the market place a noble square, and the church is large and spacious, with a curious spire, which, were not Grantham so near, might pass for the finest and highest in all this part of England: The Trent divides itself here, and makes an island, and the bridges lead just to the foot of the castle wall; so that while this place was in the hands of any party, there was no travelling but by their leave; But all the travelling into the north at that time was by Nottingham Bridge

Letter 9

Passing Newark Bridge, we went through the lower side of Nottinghamshire, keeping within the River Idle. Here we saw Tuxford in the Clays, that is to say, Tuxford in the Dirt, and a little dirty market town it is, suitable to its name.

Then we saw Rhetford, a pretty little borough town of good trade, situate on the River Idle; the mayor treated us like gentlemen, though himself but a tradesman; he gave us a dish of fish from the River Idle, and another from the Trent, which I only note, to intimate that the salmon of the Trent is very valuable in this country, and is oftentimes brought to London, exceeding large and fine; at Newark they have it very large, and like wise at Nottingham.

From Rhetford, the country on the right or east lies low and marshy, till, by the confluence of the Rivers Trent, Idle, and Don, they are formed into large islands, of which the first is called the Isle of Axholm, where the lands are very rich, and feed great store of cattle: But travelling into those parts being difficult, and sometimes dangerous, especially for strangers, we contented our selves with having the country described to us, as above, and with being assured that there were no towns of note, or any thing to be call’d curious, except that they dig old fir trees out of the ground in the Isle of Axholm, which they tell us have lain there ever since the Deluge; but, as I shall meet with the like more eminently in many other places, I shall content my self with speaking of it once for all, when we come into Lancashire.

Lincoln

Letter 7

Lincoln is an antient, ragged, decay’d, and still decaying city; it is so full of the ruins of monasteries and religious houses, that, in short, the very barns, stables, out-houses, and, as they shew’d me, some of the very hog-styes, were built church-fashion; that is to say, with stone walls and arch’d windows and doors. There are here 13 churches, but the meanest to look on that are any where to be seen; the cathedral indeed and the ruins of the old castle are very venerable pieces of antiquity.

The situation of the city is very particular; one part is on the flat and in a bottom, so that the Wittham, a little river that runs through the town, flows sometimes into the street, the other part lies upon the top of a high hill, where the cathedral stands, and the very steepest part of the ascent of the hill is the best part of the city for trade and business.

Nothing is more troublesome than the communication of the upper and lower town, the street is so steep and so strait, the coaches and horses are oblig’d to fetch a compass another way, as well on one hand as on the other.

The city was a large and flourishing place at the time of the Norman Conquest, tho’ neither the castle or the great church were then built; there were then three and fifty parish churches in it, of which I think only thirteen remain; the chief extent of the city then was from the foot of the hill south, and from the lake or lough which is call’d Swanpool east; and by the Domesday Book they tell us it must be one of the greatest cities in England, whence perhaps that old English proverbial line:

Lincoln was, London is, and York shall be.

Doncaster

Letter 8

Doncaster is a noble, large, spacious town, exceeding populous, and a great manufacturing town, principally for knitting; also as it stands upon the great northern post-road, it is very full of great inns; and here we found our landlord at the post-house was mayor of the town as well as post-master, that he kept a pack of hounds, was company for the best gentlemen in the town or in the neighbourhood, and lived as great as any gentleman ordinarily did.

Here we saw the first remains or ruins of the great Roman highway, which, though we could not perceive it before, was eminent and remarkable here, just at the entrance into the town; and soon after appeared again in many places: Here are also two great, lofty, and very strong stone bridges over the Don, and a long causeway also beyond the bridges, which is not a little dangerous to passengers when the waters of the Don are restrained, and swell over its banks, as is sometimes the case.

Pontefract

Letter 8

But I must go back to Pontefract, to take notice, that here again the great Roman highway, which I mentioned at Doncaster, and which is visible from thence in several places on the way to Pontefract, though not in the open road, is apparent again, and from Castleford Bridge, which is another bridge over the united rivers of Aire and Calder, it goes on to Abberforth, a small market town famous for pin-making, and so to Tadcaster and York. But I mention it here on this present occasion, for otherwise these remains of antiquity are not my province in this undertaking; I say, ’tis on this occasion.

1. That in some places this causeway being cut into and broken up, the eminent care of the Romans for making firm causeways for the convenience of carriage, and for the passing of travellers, is to be seen there. The layings of different sorts of earth, as clay at the bottom, chalk upon that, then gravel upon the chalk, then stones upon the gravel, and then gravel again; and so of other kinds of earth, where the first was not to be had.

2. In some places between this bridge and the town of Abberforth, the causeway having not been used for the ordinary road, it lies as fair and untouch’d, the surface covered with turf, smooth as at its first making, not so much as the mark of a hoof or of a wheel upon it; so that it is to be seen in its full dimensions and heighth, as if it had been made but the same week; whereas ’tis very probable it had stood so fifteen or sixteen hundred years; and I take notice of it here, because I have not seen any thing like it in any other place in England, and because our people, who are now mending the roads almost every where, might take a pattern from it.

York

Letter 9

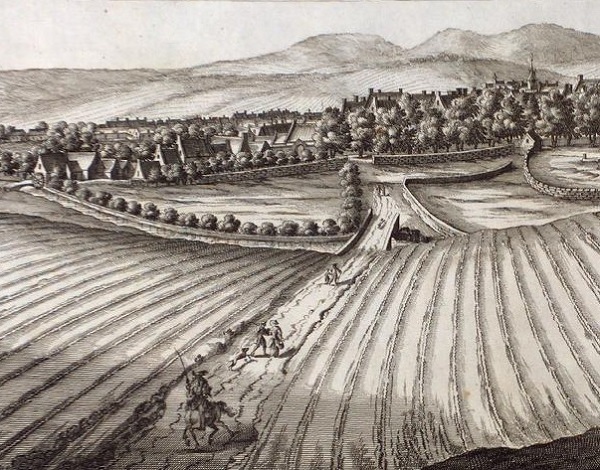

On this road we pass’d over Towton, that famous field where the most cruel and bloody battle was fought between the two Houses of Lancaster and York, in the reign of Edward IV. I call it most cruel and bloody, because the animosity of the parties was so great, that tho’ they were countrymen and Englishmen, neighbours, nay, as history says, relations; for here fathers kill’d their sons, and sons their fathers; yet for some time they fought with such obstinacy and such rancour, that, void of all pity and compassion, they gave no quarter, and I call it the most bloody, because ’tis certain no such numbers were ever slain in one battle in England, since the great battle between King Harold and William of Normandy, call’d the Conqueror, at Battle in Sussex; for here, at Towton, fell six and thirty thousand men on both sides, besides the wounded and prisoners (if they took any).

Tradition guided the country people, and they us, to the very spot; but we had only the story in speculation; for there remains no marks, no monument, no remembrance of the action, only that the ploughmen say, that sometimes they plough up arrow-heads and spear-heads, and broken javelins, and helmets, and the like; for we cou’d only give a short sigh to the memory of the dead, and move forward.

Tadcaster has nothing that we could see to testify the antiquity it boasts of, but some old Roman coins, which our landlord the post master shewed us, among which was one of Domitian, the same kind, I believe, with that Mr. Cambden gives an account of, but so very much defaced with age, that we could read but D O, and A V, at a distance. Here is the hospital and school, still remaining, founded by Dr. Oglethorp, Bishop of Carlisle, who, for want of a Protestant archbishop, set the crown on the head of Queen Elizabeth.

Here also we saw plainly the Roman highway, which I have mentioned, as seen at Aberforth; and, as antient writers tell us, of a stately stone bridge here, I may tell you, here was no bridge at all; but perhaps no writer after me will ever be able to say the like; for the case was this, the antient famous bridge, which, I suppose, had stood several hundred years, being defective, was just pull’d down, and the foundation of a new bridge, was laid, or rather begun to be laid, or was laying; and we were obliged to go over the river in a ferry boat; but coming that way since, I saw the new bridge finished, and very magnificent indeed it is.

Mr. Cambden gives us a little distich of a learned passenger upon this river, and the old bridge, at Tadcaster; I suppose he pass’d it in a dry summer, as the Frenchman did the bridge at Madrid, which I mentioned before.

Nil Tadcaster habes muris vel carmine dignum,

Præter magnifice structum sine flumine pontem.

But I can assure the reader of this account, that altho’ I pass’d this place in the middle of summer, we found water enough in the river, so that there was no passing it without a boat.

From Tadcaster it is but twelve miles to York; the country is rich, fruitful and populous, but not like the western parts about Leeds, Wakefield, Hallifax, &. which I described above; it bears good corn, and the city of York being so near, and having the navigation of so many rivers also to carry it to Hull, they never want a good market for it.

The antiquity of York, though it was not the particular enquiry I proposed to make, yet shewed it self so visibly at a distance, that we could not but observe it before we came quite up to the city, I mean the mount and high hills, where the antient castle stood, which, when you come to the city, you scarcely see, at least not so as to judge of its antiquity.

The cathedral, or the minster, as they call it, is a fine building, but not so antient as some of the other churches in the city seem to be: That mount I mentioned above, and which, at a distance, I say was a mark of antiquity, is called the old Bale, which was some ages ago fortified and made very strong; but time has eaten through not the timber and plank only, which they say it was first built with, but even the stones and mortar; for not the least footstep of it remains but the hill.

York is indeed a pleasant and beautiful city, and not at all the less beautiful for the works and lines about it being demolished, and the city, as it may be said, being laid open, for the beauty of peace is seen in the rubbish; the lines and bastions and demolished fortifications, have a reserved secret pleasantness in them from the contemplation of the publick tranquility, that outshines all the beauty of advanced bastions, batteries, cavaliers, and all the hard named works of the engineers about a city.

I shall not entertain you either with a plan of the city, or a draught of its history; I shall only say in general, the first would take up a great deal of time, and the last a great deal of paper; it is enough to tell you, that as it has been always a strong place, so it has been much contended for, been the seat of war, the rendezvous of armies, and of the greatest generals several times.

It boasts of being the seat of some of the Roman emperors, and the station of their forces for the north of Britain, being it self a Roman colony, and the like, all which I leave as I find it; it may be examined critically in Mr. Cambden, and his continuator, where it is learnedly debated. However, this I must not omit, namely, that Severus and Constantius Chlorus, father to Constantine the Great, both kept their Courts here, and both died here. Here Constantine the Great took upon him the purple, and began the first Christian empire in the world; and this is truly and really an honour to the city of York; and this is all I shall say of her antiquity.

But now things infinitely modern, compared to those, are become marks of antiquity; for even the castle of York, built by William the Conqueror, anno 1069. almost eight hundred years since Constantine, is not only become antient and decayed, but even sunk into time, and almost lost and forgotten; fires, sieges, plunderings and devastations, have often been the fate of York; so that one should wonder there should be any thing of a city left.

But ’tis risen again, and all we see now is modern; the bridge is vastly strong, and has one arch which, they tell me, was near 70 foot in diameter; it is, without exception, the greatest in England, some say it’s as large as the Rialto at Venice, though I think not.

Bridge and houses at York, William Marlow, c1760

The cathedral too is modern; it was begun to be built but in the time of Edward the First, anno 1313. or thereabouts, by one John Roman, who was treasurer for the undertaking; the foundation being laid, and the whole building designed by the charitable benevolence of the gentry, and especially, as a noted antiquary there assured me, by the particular application of two eminent families in the north, namely, the Piercys and Vavasors, as is testified by their arms and portraits cut in the stone work; the first with a piece of timber, and the last with a hew’d stone in their hands; the first having given a large wood, and the latter a quarry of stone, for encouraging the work.

It was building during the lives of three archbishops, all of the Christian name of John, whereof the last, (viz.) John Thoresby, lived to see it finished, and himself consecrated it.

It is a Gothick building, but with all the most modern addenda that order of building can admit; and with much more ornament of a singular kind, than we see any thing of that way of building grac’d with. I see nothing indeed of that kind of structure in England go beyond it, except it be the building we call King Henry VIIth’s Chapel, additional to the abbey church of Westminster, and that is not to be named with this, because it is but a chapel, and that but a small one neither.

York Minster, Henry Shaw c1848

The royal chapel at Windsor, and King’s College Chapel, at Cambridge, are indeed very gay things, but neither of them can come up to the minster of York on many accounts; also the great tower of the cathedral church at Canterbury is named to match with this at York; but this is but a piece of a large work, the rest of the same building being mean and gross, compared with this at York.

The only deficiency I find at York Minster, is the lowness of the great tower, or its want of a fine spire upon it, which, doubtless, was designed by the builders; he that lately writing a description of this church, and that at Doncaster, placed high fine spires upon them both, took a great deal of pains to tell us he was describing a place where he had never been, and that he took his intelligence grossly upon trust.

As then this church was so compleatly finished, and that so lately that it is not yet four hundred years old, it is the less to be wondered that the work continues so firm and fine, that it is now the beautifullest church of the old building that is in Britain. In a word, the west end is a picture, and so is the building, the outsides of the quire especially, are not to be equall’d.

The choir of the church, and the proper spaces round and behind it, are full of noble and magnificent monuments, too many to enter upon the description of them here, some in marble, and others in the old manner in brass, and the windows are finely painted; but I could find no body learned enough in the designs that could read the histories to us that were delineated there.

The Chapter-House is a beauty indeed, and it has been always esteemed so, witness the Latin verse which is written upon it in letters of gold.

Ur Rosa flos florum, sic est Domus ista Domorum.

But, allowing this to be a little too much of a boast, it must be own’d to be an excellent piece of work, and indeed so is the whole minster; ?or does it want any thing, as I can suppose, but, as I said before, a fine spire upon the tower, such a one as is at Grantham, or at Newark. The dimensions of this church shall conclude my description of it.

Feet.

It is in length, exclusive of the buttresses – 524½

Breadth at the east end -105

At the west end – 109

In the cross – 222

Heighth of the nave of the roof – 99

But to return to the city it self; there is abundance of good company here, and abundance of good families live here, for the sake of the good company and cheap living; a man converses here with all the world as effectually as at London; the keeping up assemblies among the younger gentry was first set up here, a thing other writers recommend mightily as the character of a good country, and of a pleasant place; but which I look upon with a different view, and esteem it as a plan laid for the ruin of the nation’s morals, and which, in time, threatens us with too much success that way.

However, to do the ladies of Yorkshire justice, I found they did not gain any great share of the just reproach which in some other places has been due to their sex; nor has there been so many young fortunes carried off here by half-pay men, as has been said to be in other towns, of merry fame, westward and southward.

The government of the city is that of a regular corporation, by mayor, aldermen and common-council; the mayor has the honour here, by antient prescription, of being called My Lord; it is a county within its self, and has a jurisdiction extended over a small tract of land on the west suburb, called the Liberty of Ansty, which I could get no uniform account of, one pretending one thing, one another. The city is old but well built; and the clergy, I mean such as serve in, and depend upon the cathedral, have very good houses, or little palaces rather here, adjoining the cymeterie, or churchyard of the minster; the bishop’s is indeed called a palace, and is really so; the deanery is a large, convenient and spacious house; and among these dwellings of the clergy is the assembly house. Whence I would infer, the conduct of it is under the better government, or should be so.

No city in England is better furnished with provisions of every kind, nor any so cheap, in proportion to the goodness of things; the river being so navigable, and so near the sea, the merchants here trade directly to what part of the world they will; for ships of any burthen come up within thirty mile of the city, and small craft from sixty to eighty ton, and under, come up to the very city.

With these they carry on a considerable trade; they import their own wines from France and Portugal, and likewise their own deals and timber from Norway; and indeed what they please almost from where they please; they did also bring their own coals from Newcastle and Sunderland, but now have them down the Aire and Calder from Wakefield, and from Leeds, as I have said already.

The publick buildings erected here are very considerable, such as halls for their merchants and trades, a large town-house or guild-hall, and the prison, which is spacious, and takes up all the ground within the walls of the old castle, and, in a building newly erected there, the assizes for the county are kept. The old walls are standing, and the gates and posterns; but the old additional works which were cast up in the late rebellion, are slighted; so that York is not now defensible as it was then: But things lie so too, that a little time, and many hands, would put those works into their former condition, and make the city able to stand out a small siege. But as the ground seems capable by situation, so an ingenious head, in our company, taking a stricter view of it, told us, he would undertake to make it as strong as Tourney in Flanders, or as Namure, allowing him to add a citadel at that end next the river. But this is a speculation; and ’tis much better that we should have no need of fortified towns than that we should seek out good situations to make them.

While we were at York, we took one day’s time to see the fatal field called Marston Moor, where Prince Rupert, a third time, by his excess of valour, and defect of conduct, lost the royal army, and had a victory wrung out of his hands, after he had all the advantage in his own hands that he could desire: Certain it is, that charging at the head of the right wing of horse with that intrepid courage that he always shewed, he bore down all before him in the very beginning of the battle, and not only put the enemies cavalry into confusion, but drove them quite out of the field.

Could he have bridled his temper, and, like an old soldier, or rather an experienced general, have contented himself with the glory of that part, sending but one brigade of his troops on in the pursuit, which had been sufficient to have finished the work, and have kept the enemies from rallying, and then with the rest of his cavalry, wheeled to the left, and fallen in upon the croup of the right wing of the enemies cavalry, he had made a day of it, and gained the most glorious victory of that age; for he had a gallant army. But he followed the chace clear off, and out of the field of battle; and when he began to return, he had the misfortune to see that his left wing of horse was defeated by Fairfax and Cromwell, and to meet his friends flying for their lives; so that he had nothing to do but to fly with them, and leave his infantry, and the Duke, then Marquis of Newcastle’s, old veteran soldiers to be cut in pieces by the enemy.

I had one gentleman with me, an old soldier too, who, though he was not in the fight, yet gave us a compleat account of the action from his father’s relation, who, he said, had served in it, and who had often shew’d him upon the very post every part of the engagement where every distinct body was drawn up, how far the lines extended, how the infantry were flank’d by the cavalry, and the cavalry by the woods, where the artillery were planted, and which way they pointed; and he accordingly described it in so lively a manner to me, that I thought it was as if I had just now seen the two armies engaging.

His relation of Prince Rupert’s ill conduct, put me in mind of the quite different conduct of old General Tilly, who commanded the imperial army at the great Battle of Leipsick in Germany, against that glorious Prince Gustavus Adolphus.

Upon the first charge, the cavalry of the right wing of Tilly’s army, commanded by the Count of Furstemburgh, fell on with such fury, and in such excellent order, being all old troops, and most of them cuirassers, upon the Saxon troops, which had the left of the Swedish army, and made twenty two thousand men, that, in short, they put them into confusion, and drove them upon their infantry of the main battle, so that all went off together except General Arnheim, who commanded the Saxon right wing, and was drawn up next to the Swedes.

The Saxons being thus put into confusion, the Imperialists cried Victoria, the enemy fly , and their general officers cry’d out to Tilly to let them follow. No, says Tilly, let ’em go, let ’em go; but let us beat the Swedes too, or we do nothing; and immediately he ordered the cavalry that had performed so well, should face to the left, and charge the rest of the army in flank. But the King of Sweden, who saw the disorder, and was ready at all places to encourage and direct his troops, ordered six thousand Scots, under Sir John Hepburn, who made his line of reserve, to make a front to the left, and face the victorious troops of the Imperialists, while, in the mean time, with a fury not to be resisted, he charg’d, in person, upon the Imperial left wing, and bore down all before him.

Then it appeared that Count Tilly was in the right; for though he had not let his right wing pursue the Saxons, who, notwithstanding being new men, never rallied, yet with his whole army he was not able to beat the rest; but the King of Sweden gained the most glorious victory that ever a Protestant army had till then obtain’d in the world over a Popish. This was 1632.

I came back extremely well pleased with the view of Marston Moor, and the account my friend had given of the battle; ’twas none of our business to concern our passions in the cause, or regret the misfortunes of that day; the thing was over beyond our ken; time had levelled the victors with the vanquished, and the royal family being restored, there was no room to say one thing or other to what was pass’d; so we returned to York the same night.

York, as I have said, is a spacious city, it stands upon a great deal of ground, perhaps more than any city in England out of Middlesex, except Norwich; but then the buildings are not close and throng’d as at Bristol, or as at Durham, nor is York so populous as either Bristol or Norwich. But as York is full of gentry and persons of distinction, so they live at large, and have houses proportioned to their quality; and this makes the city lie so far extended on both sides the river. It is also very magnificent, and, as we say, makes a good figure every way in its appearance, even at a distance; for the cathedral is so noble and so august a pile, that ’tis a glory to all the rest.

There are very neat churches here besides the cathedral, and were not the minster standing, like the Capitol in the middle of the city of Rome, some of these would pass for extraordinary, as the churches of St. Mary’s and Allhallows, and the steeples of Christ-Church, St. Mary’s, St. Pegs, and Allhallows.

There are also two fine market-houses, with the town-hall upon the bridge, and abundance of other publick edifices, all which together makes this city, as I said, more stately and magnificent, though not more populous and wealthy, than any other city in the king’s dominions, London and Dublin excepted. The reason of the difference is evidently for the want of trade.

Here is no trade indeed, except such as depends upon the confluence of the gentry: But the city, as to lodgings, good houses, and plenty of provisions, is able to receive the King, Lords and Commons, with the whole Court, if there was occasion; and once they did entertain King Charles I. with his whole Court, and with the assembly of Peers, besides a vast confluence of the gentry from all parts to the king, and at the same time a great part of his army.

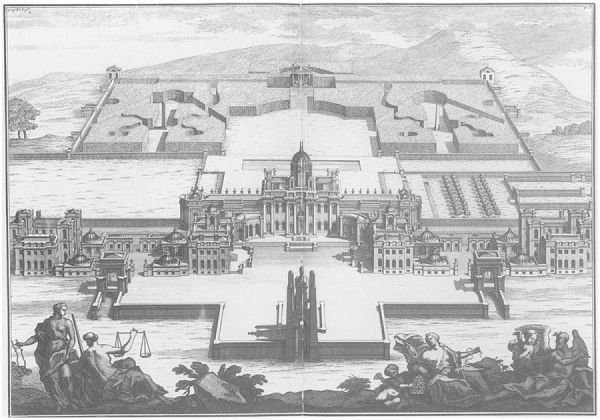

We went out in a double excursion from this city, first to see the Duke of Leeds’s house, and then the Earl of Carlisle’s, and the Earl of Burlington’s in the East Riding; Carlisle House is by far the finest design, but it is not finished, and may not, perhaps, in our time; they say his lordship sometimes observes noblemen should only design, and begin great palaces, and leave posterity to finish them gradually, as their estates will allow them; it is called Castle Howard. The Earl of Burlington’s is an old built house, but stands deliciously, and has a noble prospect towards the Humber, as also towards the Woulds.

This 1720s engraving showed the original plans for Castle Howard and was published in Vitruvius Britannicus. By this time the house was taking shape though the west wing would take many decades longer.

At Hambledon Down, near this city, are once a year very great races, appointed for the entertainment of the gentry, and they are the more frequented, because the king’s plate of a hundred guineas is always run for there once a year; a gift designed to encourage the gentlemen to breed good horses.

Yorkshire is throng’d with curiosities, and two or three constantly attend these races, namely, First, That (as all horse matches do) it brings together abundance of noblemen and gentlemen of distinction, and a proportion of ladies; and, I assure you, the last make a very noble appearance here, and, if I may speak my thoughts without flattery, take the like number where you will, yet, in spite of the pretended reproach of country breeding, the ladies of the north are as handsome and as well dress’d as are to be seen either at the Court or the Ball.

Boroughbridge

Letter 8

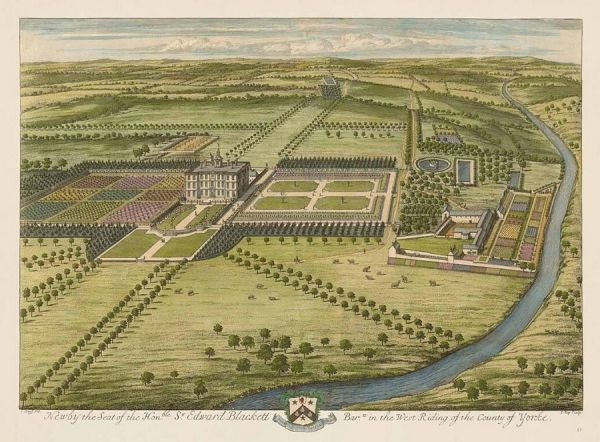

A mile from this town, or less, is a stately beautiful seat, built a few years since by Sir Edward Blacket [Newby Hall] the park is extended to the bank of the River Eure, and is sometimes in part laid under water by the river, the water of which, they say, coming down from the western mountains, thro’ a marly, loamy soil, fructifies the earth, as the River Nile does the Egyptian fields about Grand Cairo, tho’ by their leave not quite so much.

Newby Hall was built between 1691 and 1695

As Sir Edward spared no cost in the building, and Sir Christopher Wren laid out the design, as well as chose the ground for him, you may believe me the better, when I add, that nothing can either add to the contrivance or the situation; the building is of brick, the avenues, now the trees are grown, are very fine, and the gardens not only well laid out, but well planted, and as well kept; the statues are neat, the parterre beautiful; but, as they want fine gravel, the walks cannot shew themselves, as in this southern part of England they would. The house has a fine prospect over the country, almost to York, with the river in view most of the way; and it makes it self a very noble appearance to the great north road, which lies within two miles of it, at Burrow-bridge.

As you now begin to come into the North Riding, for the Eure parts the West Riding from it, so you are come into the place noted in the north of England for the best and largest oxen, and the finest galloping horses, I mean swift horses, horses bred, as we call it, for the light saddle, that is to say, for the race, the chace, for running or hunting. Sir Edward was a grazier, and took such delight in the breeding and feeding large siz’d black cattle, that he had two or three times an ox out of his park led about the country for a sight, and shewed as far as Newcastle, and even to Scotland, for the biggest bullock in England; nor was he very often, if ever, over-match’d.

From this town of Rippon, the north road and the Roman highway also, mentioned before, which comes from Castleford Bridge, parting at Abberforth, leads away to a town call’d Bedal, and, in a strait line (leaving Richmond about two miles on the west) call’d Leeming Lane, goes on to Piersbridge on the River Tees, which is the farthest boundary of the county of York.

But before I go forward I should mention Burrow Bridge, which is but three miles below Rippon, upon the same River Eure, and which I must take in my way, that I may not be obliged to go farther out of the way, on the next journey.

There is something very singular at this town, and which is not to be found in any other part of England or Scotland, namely, two borough towns in one parish, and each sending two members to Parliament, that is, Borough Brigg and Aldborough.

Borough Brigg, or Bridge, seems to be the modern town risen up out of Aldborough, the very names importing as much, (viz.) that Burrough at the Bridge, and the Old Borough that was before; and this construction I pretend to justify from all the antiquaries of our age, or the last, who place on the side of Aldborough or Old Borough, an antient city and Roman colony, call’d Isurium Brigantum ; the arguments brought to prove the city stood here, where yet at present nothing of a city is to be seen, no not so much as the ruines, especially not above ground, are out of my way for the present; only the digging up coins, urns, vaults, pavements, and the like, may be mentioned, because some of them are very eminent and remarkable ones, of which an account is to be seen at large in Mr. Cambden, and his continuator, to whom I refer. That this Old Burrough is the remain of that city, is then out of doubt, and that the Burrough at the Bridge, is since grown up, and perhaps principally by the confluence of travellers, to pass the great bridge over the Eure there; this seems too out of question by the import of the word. How either of them came to the privilege of sending members to Parliament, whether by charter and incorporation, or meer prescription, that is to say, a claim of age, which we call time out of mind, that remains for the Parliament to be satisfied in. Certain it is, that the youngest of the two, that is, Burrow Bridge, is very old; for here, in the barons wars, was a battle, and on this bridge the great Bohun, Earl of Hereford, was killed by a soldier, who lay concealed under the bridge, and wounded him, by thrusting a spear or pike into his body, as he pass’d the bridge. From whence Mr. Cambden very gravely judges, that it was not a stone bridge as is now, but a bridge of timber, a thing any man might judge without being challenged for a wizard.

I had not the curiosity so much as to go to see the four great stones in the fields on the left-hand, as you go through Burrow Bridge, which the country people, because they wonder how they could come there, will have be brought by the devil, and call them the Devil’s Bolts. Mr. Cambden describes them, and they are no more than are frequent; and I have been obliged to speak of such so often, that I need say no more, but refer to other authors to describe the Romans way of setting up trophies for victory, or the dead, or places of sacrifices to their gods, and which soever it may be, the matter is the same.

From the Eure entring the North Riding, and keeping the Roman causeway, as mentioned before, one part of which went by this Isurium Brigantum from York, we come to Bedall, all the way from Hutton, or thereabout, this Roman way is plain to be seen, and is called now Leeming Lane, from Leeming Chapel, a village which it goes through.

I met with nothing at or about Bedall, that comes within the compass of my enquiry but this, that not this town only, but even all this country, is full of jockeys, that is to say, dealers in horses, and breeders of horses, and the breeds of their horses in this and the next country are so well known, that tho’ they do not preserve the pedigree of their horses for a succession of ages, as they say they do in Arabia and in Barbary, yet they christen their stallions here, and know them, and will advance the price of a horse according to the reputation of the horse he came of.

They do indeed breed very fine horses here, and perhaps some of the best in the world, for let foreigners boast what they will of barbs and Turkish horses, and, as we know five hundred pounds has been given for a horse brought out of Turkey, and of the Spanish jennets from Cordova, for which also an extravagant price has been given, I do believe that some of the gallopers of this country, and of the bishoprick of Durham, which joins to it, will outdo for speed and strength the swiftest horse that was ever bred in Turkey, or Barbary, take them all together.

My reason for this opinion is founded upon those words altogether; that is to say, take their strength and their speed together; for example; match the two horses, and bring them to the race post, the barb may beat Yorkshire for a mile course, but Yorkshire shall distance him at the end of four miles; the barb shall beat Yorkshire upon a dry, soft carpet ground, but Yorkshire for a deep country; the reason is plain, the English horses have both the speed and the strength; the barb perhaps shall beat Yorkshire, and carry seven stone and a half; but Yorkshire for a twelve to fourteen stone weight; in a word, Yorkshire shall carry the man, and the barb a feather.

The reason is to be seen in the very make of the horses. The barb, or the jennet, is a fine delicate creature, of a beautiful shape, clean limbs, and a soft coat; but then he is long jointed, weak pastured, and under limb’d: Whereas Yorkshire has as light a body, and stronger limbs, short joints, and well bon’d. This gives him not speed only but strength to hold it; and, I believe, I do not boast in their behalf, without good vouchers, when I say, that English horses, take them one with another, will beat all the world.

As this part of the country is so much employed in horses, the young fellows are naturally grooms, bred up in the stable, and used to lie among the horses; so that you cannot fail of a good servant here, for looking after horses is their particular delight; and this is the reason why, whatever part of England you go to, though the farthest counties west and south, and whatever inn you come at, ’tis two to one but the hostler is a Yorkshire man; for as they are bred among horses, ’tis always the first business they recommend themselves to; and if you ask a Yorkshire man, at his first coming up to get a service, what he can do; his answer is, sir, he can look after your horse, for he handles a curry-comb as naturally as a young scrivener does a pen and ink.

Besides their breeding of horses, they are also good grasiers over this whole country, and have a large, noble breed of oxen, as may be seen at North Allerton fairs, where there are an incredible quantity of them bought eight times every year, and brought southward as far as the fens in Lincolnshire, and the Isle of Ely, where, being but, as it were, half fat before, they are fed up to the grossness of fat which we see in London markets. The market whither these north country cattle are generally brought is to St. Ives, a town between Huntingdon and Cambridge, upon the River Ouse, and where there is a very great number of fat cattle every Monday.

Richmond

Letter 8

Richmond, which, as I said, is two or three mile wide of the Leeming Lane, is a large market town, and gives name to this part of the country, which is called after it Richmondshire, as another part of it east of this is call’d North Allertonshire. Here you begin to find a manufacture on foot again, and, as before, all was cloathing, and all the people clothiers, here you see all the people, great and small, a knitting; and at Richmond you have a market for woollen or yarn stockings, which they make very coarse and ordinary, and they are sold accordingly; for the smallest siz’d stockings for children are here sold for eighteen pence per dozen, or three half pence a pair, somctimes less.

This trade extends itself also into Westmoreland, or rather comes from Westmoreland, extending itself hither, for at Kendal, Kirkby Stephen, and such other places in this county as border upon Yorkshire; the chief manufacture of yarn stockings is carried on; it is indeed a very considerable manufacture in it self, and of late mightily encreased too, as all the manufactures of England indeed are.

This town of Richmond (Cambden calls it a city) is wall’d, and had a strong castle; but as those things are now all slighted, so really the account of them is of small consequence, and needless; old fortifications being, if fortification was wanted, of very little signification; the River Swale runs under the wall of this castle, and has some unevenness at its bottom, by reason of rocks which intercept its passage, so that it falls like a cataract, but not with so great a noise.

Letter 9

North Allerton, a town on the post road, is remarkable for the vast quantity of black cattle sold there, there being a fair once every fortnight for some months, where a prodigious quantity are sold.

I have not concern’d this work at all in the debate among us in England, as to Whig and Tory. But I must observe of this town, that, except a few Quakers, they boasted that they had not one Dissenter here, and yet at the same time not one Tory, which is what, I believe, cannot be said of any other town in Great Britain.

Darlington

Letter 9

Darlington, a post town, has nothing remarkable but dirt, and a high stone bridge over little or no water, the town is eminent for good bleaching of linen, so that I have known cloth brought from Scotland to be bleached here. As to the Hell Kettles, so much talked up for a wonder, which are to be seen as we ride from the Tees to Darlington, I had already seen so little of wonder in such country tales, that I was not hastily deluded again. ‘Tis evident, they are nothing but old coal pits filled with water by the River Tees.

Durham

Letter 8

Leaving Richmond, we continue through this long Leeming Lane, which holds for about the length of six mile to the bank of Tees, where we pass’d over the River Tees at Piersbridge; the Tees is a most terrible river, so rapid, that they tell us a story of a man who coming to the ferry place in the road to Darlington, and finding the water low began to pull off his hose and shoes to wade thro’, the water not being deep enough to reach to his knees, but that while he was going over, the stream swell’d so fast as to carry him away and drown him.

This bridge leads into the bishoprick of Durham, and the road soon after turns into the great post road leading to the city of Durham. I shall dwell no longer upon the particulars found on this side except Barnard Castle, which is about four miles distant from the Tees bank west, and there I may speak of it again; as all the country round here are grooms, as is noted before; so here and hereabouts they have an excellent knack at dressing horses hides into leather, and thinking or making us think it is invulnerable, that is to say, that it will never wear out; in a word, they make the best bridle reins, belts broad or narrow, and all accoutrements for a compleat horse-master, as they do at Rippon for spurs and stirrups.

Barnard’s Castle stands on the north side of the Tees, and so is in the bishoprick of Durham. ‘Tis an antient town, and pretty well built, but not large; the manufacture of yarn stockings continues thus far, but not much farther; but the jockeys multiply that way; and here we saw some very fine horses indeed; but as they wanted no goodness, so they wanted no price, being valued for the stallion they came of, and the merit of the breed.

Letter 9

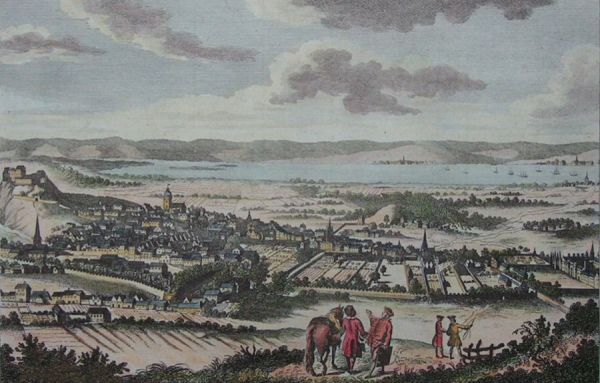

Durham is next, a little compact neatly contriv’d city, surrounded almost with the River Wear, which with the castle standing on an eminence, encloses the city in the middle of it; as the castle does also the cathedral, the bishop’s palace, and the fine houses of the clergy, where they live in all the magnificence and splendour imaginable.

I need not tell you, that the Bishop of Durham is a temporal prince, that he keeps a court of equity, and also courts of justice in ordinary causes within himself. The county of Durham, like the country about Rome, is called St. Cuthbert’s Patrimony. This church, they tell us, was founded by David, King of Scots; and afterward Zouch, the valiant bishop, fought the Scots army at Nevil’s Cross, where the Scots were terribly cut in pieces, and their king taken prisoner.

But what do I dip into antiquity for, here, which I have avoided as much as possible every where else? The church of Durham is eminent for its wealth; the bishoprick is esteemed the best in England; and the prebends and other church livings, in the gift of the bishop, are the richest in England. They told me there, that the bishop had thirteen livings in his gift, from five hundred pounds a year to thirteen hundred pounds a year; and the living of the little town of Sedgfield, a few miles south of the city, is said to be worth twelve hundred pounds a year, beside the small tithes, which maintain a curate, or might do so.

Going to see the church of Durham, they shewed us the old Popish vestments of the clergy before the Reformation, and which, on high days, some of the residents put on still. They are so rich with embroidery and emboss’d work of silver, that indeed it was a kind of a load to stand under them.

The town is well built but old, full of Roman Catholicks, who live peaceably and disturb no body, and no body them; for we being there on a holiday, saw them going as publickly to mass as the Dissenters did on other days to their meeting-house.

From hence we kept the common road to Chester in the Street, an old, dirty, thorowfare town, empty of all remains of the greatness which antiquaries say it once had, when it was a Roman colony. Here is a stone bridge, but instead of riding over it we rode under it, and riding up the stream pass’d under or through one of the arches, not being over the horse hoofs in water; yet, on enquiry, we found, that some times they have use enough for a bridge.

Here we had an account of a melancholy accident, and in it self strange also, which happened in or near Lumley Park, not long before we pass’d through the town. A new coal pit being dug or digging, the workmen workt on in the vein of coals till they came to a cavity, which, as was supposed, had formerly been dug from some other pit; but be it what it will, as soon as upon the breaking into the hollow part, the pent up air got vent, it blew .up like a mine of a thousand barrels of powder, and; getting vent at the shaft of the pit, burst out with such a terrible noise, as made the very earth tremble for some miles round, and terrify’d the whole country. There were near three-score poor people lost their lives in the pit, and one or two, as we were told, who were at the bottom of the shaft, were blown quite out, though sixty fathom deep, and were found dead upon the ground.

Lumley Castle is just on the side of the road as you pass between Durham and Chester, pleasantly seated in a fine park, and on the bank of the River Were. The park, besides the pleasantness of it, has this much better thing to recommend it, namely, that it is full of excellent veins of the best coal in the country, (for the Lumley coal are known for their goodness at London, as well as there). This, with the navigable river just at hand, by which the coals are carried down to Sunderland to the ships, makes Lumley Park an inexhaustible treasure to the family.

They tell us, that King James the First lodg’d in this castle, at his entrance into England to take possession of the crown, and seeing a fine picture of the antient pedigree of the family, which carried it very far beyond what his majesty thought credible, turn’d this good jest upon it to the Bishop of Durham, who shewed it him, viz. That indeed he did not know that Adam’s sirname was Lumley before.

Lumley Castle, 1794, Edward Dayes

Newcastle

Letter 9

From hence the road to Newcastle gives a view of the in-exhausted store of coals and coal pits, from whence not London only, but all the south part of England is continually supplied; and whereas when we are at London, and see the prodigious fleets of ships which come constantly in with coals for this encreasing city, we are apt to wonder whence they come, and that they do not bring the whole country away; so, on the contrary, when in this country we see the prodigious heaps, I might say mountains, of coals, which are dug up at every pit, and how many of those pits there are; we are filled with equal wonder to consider where the people should live that can consume them.

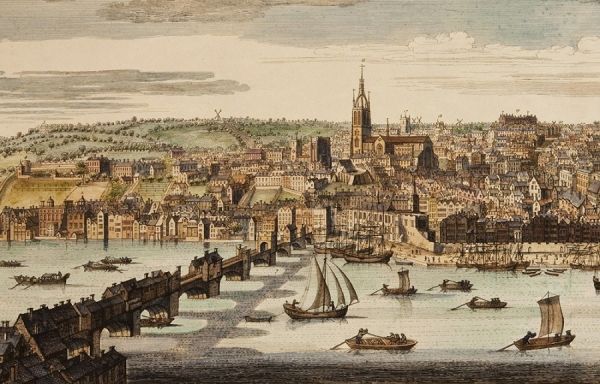

Newcastle is a spacious, extended, infinitely populous place; ’tis seated upon the River Tyne, which is here a noble, large and deep river, and ships of any reasonable burthen may come safely up to the very town. As the town lies on both sides the river, the parts are join’d by a very strong and stately stone bridge of seven very great arches, rather larger than the arches of London Bridge; and the bridge is built into a street of houses also, as London Bridge is.

The town it self, or liberty, as it is a Corporation, extends but to part of the bridge, where there is a noble gate built all of stone, not much unlike that upon London Bridge, which so lately was a safeguard to the whole bridge, by stopping a terrible fire which otherwise had endangered burning the whole street of houses on the city side of the bridge, as it did those beyond it.

There is also a very noble building here, called the Exchange: And as the wall of the town runs parallel from it with the river, leaving a spacious piece of ground before it between the water and the wall, that ground, being well wharf’d up, and fac’d with free-stone, makes the longest and largest key for landing and lading goods that is to be seen in England, except that at Yarmouth in Norfolk, and much longer than that at Bristol.

Here is a large hospital built by contribution of the keel men, by way of friendly society, for the maintenance of the poor of their fraternity, and which, had it not met with discouragements from those who ought rather to have assisted so good a work, might have been a noble provision for that numerous and laborious people. The keel men are those who manage the lighters, which they call keels; by which the coals are taken from the steaths or wharfs, and carryed on board the ships, to load them for London.

Here are several large publick buildings also, as particularly a house of state for the mayor of the town (for the time being) to remove to, and dwell in during his year: Also here is a hall for the surgeons, where they meet, where they have two skeletons of humane bodies, one a man and the other a woman, and some other rarities.

The situation of the town to the landward is exceeding unpleasant, and the buildings very close and old, standing on the declivity of two exceeding high hills, which, together with the smoke of the coals, makes it not the pleasantest place in the world to live in; but it is made amends abundantly by the goodness of the river, which runs between the two hills, and which, as I said, bringing ships up to the very keys, and fetching the coals down from the country, makes it a place of very great business. Here are also two articles of trade which are particularly occasioned by the coals, and these are glass-houses and salt pans; the first are at the town it self, the last are at Shields, seven miles below the town; but their coals are brought chiefly from the town. It is a prodigious quantity of coals which those salt works consume; and the fires make such a smoke, that we saw it ascend in clouds over the hills, four miles before we came to Durham, which is at least sixteen miles from the place.

Here I met with a remark which was quite new to me, and will be so, I suppose, to those that hear it. You well know, we receive at London every year a great quantity of salmon pickled or cured, and sent up in the pickle in kits or tubs, which we call Newcastle salmon; now when I came to Newcastle, I expected to see a mighty plenty of salmon there, but was surprized to find, on the contrary, that there was no great quantity, and that a good large fresh salmon was not to be had under five or six shillings. Upon enquiry I found, that really this salmon, that we call Newcastle salmon, is taken as far off as the Tweed, which is three-score miles, and is brought by land on horses to Shields, where it is cur’d, pickl’d, and sent to London, as above; so that it ought to be called Berwick salmon, not Newcastle.

Newcastle, Nathaniel Buck, 1745