Dere Street and the Great North Road

Dere Street is the name generally used to describe the Roman road leading from York to the Firth of Forth. It was constructed by the military to secure the colonisation of northern Britain. It traversed challenging terrain and involved difficult river crossings including the Ure, Tees, Tyne and Tweed. The Romans met significant resistance and needed a series of forts to secure the route.

The Great North Road coaching route, and the modern A1, coincide with portions of Dere Street. This is particularly the case between Boroughbridge and Scotch Corner. A few miles beyond Scotch Corner, Dere Street continues due north to Bishop Auckland then loosely follows the current day A68. Its end point is often taken to be Camelon near Falkirk where the Antonine Wall across the central belt of Scotland was established in the mid second century.

Regular upgrades to the A1 over the past 100 years have exposed details of Dere Street. This is particularly true of a major archaeological project undertaken for Highways England in advance of the Dishforth to Barton motorway scheme during the 2010s. Excellent reports by Northern Archaeological Associates provide fantastic detail on the evolution of the route from pre-Roman to modern times.

Together, Dere Street and Ermine Street represent the primary Roman route from London to Hadrian’s Wall – and indeed further into Scotland.

The following interactive map provides information on the route and major Roman locations along Dere Street. Click on a location to find a brief description and image. Please note that the route shown is “broad brush”.

If there are glaring errors or better information, please let me know and I will endeavour to improve this map – Rex Gibson

Dere Street: Names & Knowledge

We do know there was a road constructed by the Romans between York and the Firth of Forth. It was distinctive in its time, being deliberately planned and then constructed in accordance with a definite method. It was the principal road north from the legionary fortress at York to the northern border, be it in Scotland or at Hadrian’s Wall.

We don’t know what the Romans called this road. We don’t even know whether Romans thought of it as a singular defined road. We’re not sure to what extent there were pre-existing long-distance routes.

We piece together knowledge based on oblique references in scant surviving documents. We rely heavily on interpretation of archaeological evidence be it in the form of aerial survey, geophysical survey, excavation, or interpolation from other features. We need to be mindful that the route was an evolving one even during Roman times.

Dere Street

A name first recorded in the Historia De Sancto Cuthberto which dates to about 1030 but which drew on earlier sources for its content. The name was used by those in the north-east to refer to the road to Deira – the southern half of the Anglo Saxon kingdom of Northumbria (Deira approximated to North and South Yorkshire).

Watling Street

Regularly used by antiquarians who saw the road in terms of the Antonine Itinerary’s 2nd British route which reached from Richborough to Carlisle and is known further south by this name.

Margary – RR8

Coined in the 1950s by the historian Ivan Margary this terminology for Roman Roads is still widely used. Dere Street is subdivided into 7 sections, RR8a to RR8g.

Dere Street: 350 Years of Roman History

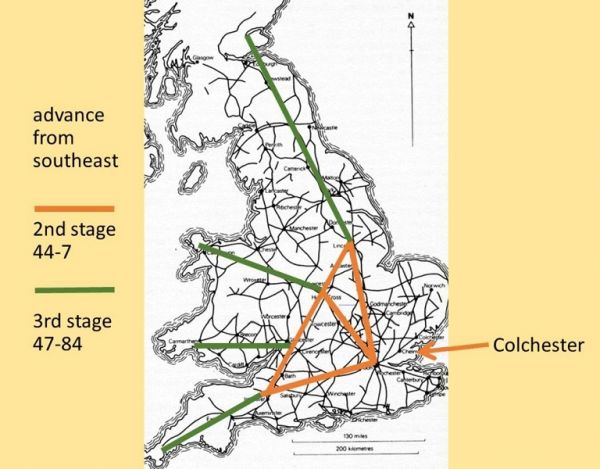

Following the Roman invasion of Britain by Emperor Claudius in AD 43, the Roman army oversaw the rapid construction of a network of new roads. They were engineered by, and constructed under the direction of, the military. The first phase concentrated in the south and east linking legionary bases with ports such as Chichester and Colchester.

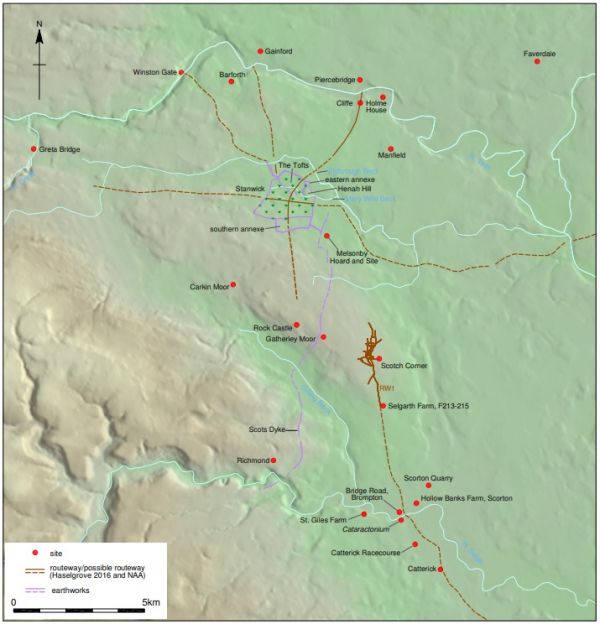

Much of the north was controlled by the Brigantes tribe, believed to have been based at Stanwick (west of Dere Street between Scotch Corner and Piercebridge). According to Tacitus, their queen, Catimandua, “ruled by right rather than through marriage” and was loyal to Rome. However, her divorced husband, Venutius, led a rebellion prompting the deployment of the Ninth Legion Hispana – and the establishment of the fortress at York in AD 71. A network of auxiliary forts spread over the region, a day’s march apart and concentrated on river crossings and other strategic locations. During his reign from AD 75 to 85, Governor Gnaeus Julius Agricola led aggressive campaigns against the “Caledonians”.

Image Credit – Nicholas James

The road building push north probably lagged first military contact by a decade or more, as it was necessary to have subdued local opposition and marshalled resources.

The east-west Stanegate, intersecting with Dere Street at Corbridge, was built in the early second century prior to construction of Hadrian’s Wall immediately to its north in the 120s. By this time Dere Street with its series of forts had been established as one of two major routes into central Scotland. The Roman presence was further secured with the construction of the Antonine Wall in the 160s.

Initial conquest required large numbers of troops, often based in temporary camps or forts which were occupied relatively briefly. A number of the forts along Dere Street initially comprised large areas secured by earth ramparts and wooden defences. Some were abandoned, some re-purposed several times, some rebuilt in stone, some spawning civilian settlements outside their walls.

The civilian settlement at York became a colonia and was of sufficient status to host three Emperors. Aldborough became the civitas capital of the Brigantes, a place of wealth and culture. Corbridge was established as a fort in 85 AD and a century later had expanded into a major military supply base for the Wall (3 miles north at Port Gate) and for periodic campaigns to the north; the northernmost town in the empire boasted an aqueduct, fountain house, granaries, workshops, a market and a monumental courtyard building.

Expansionist zeal waned as the second century progressed. The focus turned to exploitation of natural resources, trade and maintenance of security within defined areas. The Antonine Wall was only maintained for about 20 years. Towns such as York and Corbridge became important commercial centres. By the third and fourth centuries a prosperous British elite emerged which started to adopt Roman habits and beliefs.

Emperor Septimus Severus and his family established a base at York before leading a large army up Dere Street in 208 AD in response to raids by the barbarians. First century forts were re-garrisoned and fierce fighting took place beyond the old Antonine Wall. This campaign subsided with the death of Severus in York three years later, but the need to periodically tame the Caledonians continued. Emperor Constantius claimed a great victory and the title Britannicus Maximus in AD 305 before falling ill, returning to die in York.

In 367 the “Great Barbarian Conspiracy” saw a rebellion of the Hadrian’s Wall garrison allowing Picts, Attacotti and Scotti to take over large areas of western and northern Britain. A relief force under Flavius Theodosius eventually overcame the invaders, establishing a new province of Valentia.

Rome’s interest in Britain was diminishing. The last military units were withdrawn from Britain in 408 to help defend Italy. With the army gone and civil administration crumbling, infrastructure such as roads was no longer maintained, and trade dwindled. Although the Roman roads remained features of the landscape the gradual demise of key elements such as bridges would have reduced Dere Street’s importance.

From Routeway to Motorway

[This title and much of the content is borrowed from David Fell and Paul Johnstone’s excellent monograph published by Northern Archaeological Associates (NAA)]

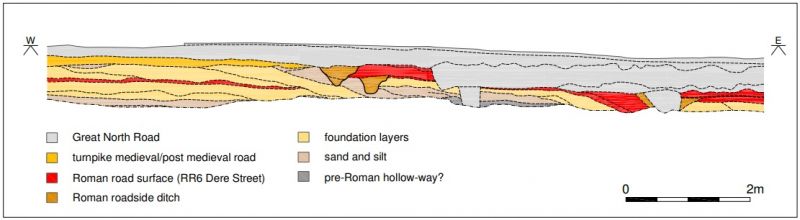

The Vales of York and Mowbray left behind by the retreating ice sheets created a natural north-south route between the Pennines to the west and the North York Moors to the east. There are signs that it may have been in use as a routeway from as early as the 4th millennium BC. It was certainly a transport route before the Romans arrived. Dere Street adopted and formalised the section between Boroughbridge and Scotch Corner as a road. The same corridor was used through medieval times, the coaching days of the 17th and 18th centuries – and in the 20th century for the A1. Archaeological investigations, often facilitated by new road building, have thrown light on the evolution of the route.

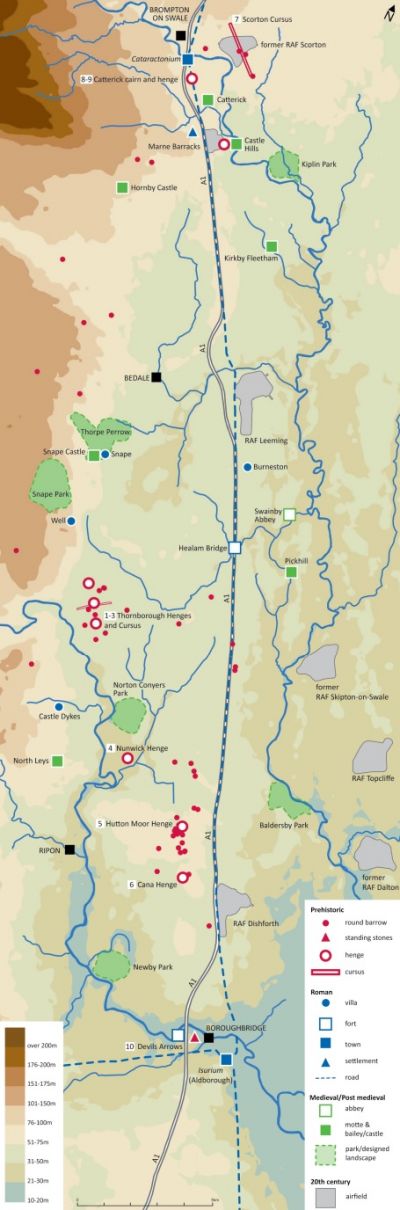

By the Neolithic (4400 BC) trackways are known to have been developing as populations started to adopt farming and more sedentary lifestyles. The location of pre-historic trackways tends to be inferred from other features and monuments which have been identified. Amongst those along the route of Dere Street are a series of striking henges and cursus monuments.

Henges and other monuments between Boroughbridge and Catterick (Image Credit – YAC)

Thornborough henge complex (Image Credit – Historic England)

Regarding henge examples from across mainland Britain, including 6 along the north-east side of the Ure, it has been noted how the orientations of their entrances commonly aligns with those of adjacent Roman roads such as Dere Street.

By the Iron Age a dense network of local tracks had emerged. There is insufficient evidence to pin down a direct predecessor to Dere Street though the pattern of routeways around the oppidum at Stanwick is starting to emerge.

Middle & late Iron Age routeways (Image Credit – NAA)

Pre-Roman aggregate hollow-way at Selgarth Farm (south of Scotch Corner), representing the precursor of Dere Street (Image Credit – NAA)

Evidence for the route and construction of Roman Dere Street is plentiful. It does not always conform to a highly standardised specification, even where the road was close to the legionary fortress at York. While the principal of a cambered agger to aid drainage was maintained, engineers employed materials that were available locally, including liberal use of rounded cobbles, pebbles, gravel, sand and clay. Road width was generally 7-8m but might be narrower where the road interacted with buildings or passed through forts and settlements. Occasionally, as at Healam Bridge, parallel carriageways were introduced to relieve congestion. Evidence from a number of sites points to regular maintenance with widening, realignment and re-surfacing.

Recording wheel ruts along Dere Street at Healam Bridge (Image Credit – NAA)

Dere Street western kerb at Agricola Bridge, Cataractonium (Image Credit – NAA)

Scotch Corner was a major settlement and, as today, an important junction with the Roman route branching to Stainmore and Carlisle (the modern A66).

A Roman junction with Dere Street exposed at Scotch Corner (Image Credit – NAA)

A section through Dere Street immediately north of the Scotch Corner roundabout (Image Credit – NAA)

Dere Street no doubt diminished in importance when the Romans left. However, there are clues that settlements along the route continued to be important into Anglo-Saxon times. Bede records that Bishop Paulinus undertook a mass baptism in the Swale by Cataracta in AD 627. Symeon of Durham records the marriages of both King Aethelwold, in AD 762, and of King Ethelred in AD7 92 as having occurred at Catterick/Brompton-on-Swale.

Sunken-featured buildings have been discovered next to Dere Street within Cataractonium to the south of the Swale, and within the northern suburb of Brompton. In 2021, Ross and Ross concluded:

“The role of Cataractonium during its later years may still have been intertwined with the importance of Dere Street. Maintenance of the Roman bridge, although potentially later than the Early Anglo-Saxon period would undoubtably have been of benefit more widely than to the occupants of the former town and may demonstrate the actions of a regional authority, which sought to ensure Dere Street could continue to operate as an all-weather long distance route.”

The 7th century Ravenna Cosmology barely qualifies as a road map but it does list the settlements of Lanchester, Binchester, Bowes, Catterick/Brompton-on-Swale, York and Brough-on-Humber in that order (Bowes is the odd one out though does lie on a former Roman trans-Pennine route).

Historical records of battles in the north-east also hint at the importance of Dere Street as a strategic long-distance route. Symeon of Durham’s account of an invasion in the early 10th century:

“a certain heathen king called Raegnald came with a large fleet and landed in Northumbria. Without delay he attacked York and either killed or drove out of their homeland all the better sort of inhabitants.”

[Other accounts suggest the invasion was from the west, and the battle was at Corbridge.]

The Norman invasion of the 11th century stimulated an echo of the local resistance encountered by the Romans. The Norman response was equally fierce. In the winter of 1069-70 William launched a campaign of intimidation and reprisals – the “Harrying of the North”. One contemporary account claims no village was inhabited between York and Durham such was the devastation and fear. The inference from these accounts is that the legacy road network was sufficient to allow William to move large numbers of troops quickly around the country.

King David’s Scottish army marched to capture York in 1138. The English army assembled at Thirsk and marched to Northallerton to defeat the invaders.

The name Dere Street starts to appear again in 12th century ecclesiastical records – probably reflecting regular use in the North East over previous centuries. Another designation to describe the former Roman road is used in a 1202 definition of the boundaries of Hutton Conyers:

By the boundary between Bishou and Kanehou and to the north by the King’s high road from Boroughbridge to the bridge of Lemming

At about this time it is thought that the Catterick-Brompton Swale bridge crossing shifted, causing variations in the north-south route. It may be that the Roman bridge at Cataractonium finally collapsed. There were alternatives upstream and downstream. In the early 1420s the medieval bridge was constructed a little to the east of the Roman route.

Saxton’s 1577 map of Yorkshire depicts bridges at Borough Bridge, Leeming Bar, Catterick and Piercebridge. William Camden in the early 17th century notes Dere Street’s Roman origins and references the junction to Bowes (ie at Scotch Corner). Ogilby’s Britannia features in detail the road from London to Berwick. It is broadly the Roman Dere Street route from York passing through Green Hamerton and Boroughbridge. It then turns eastwards to cross the Swale at Topcliffe before heading on to Northallerton then Darlington. During the coaching days of the Great North Road the section of Dere Street between Dishforth and Scotch Corner was commonly referred to as Leeming Lane and was seen as part of the route to Carlisle rather than Berwick.

The Dere Street route from Boroughbridge to Piercebridge was turnpiked in 1743, and from Boroughbridge to Durham in 1745. Investment in the route included a replacement for the formerly hump backed Healam bridge which was not coach friendly. The bridges at Boroughbridge, Catterick/Brompton-on-Swale and Piercebridge were all widened in the latter decades of the 18th century. In the early 19th century the road benefited from a “Macadamised” surface; in 1845 Lewis’s Topographical Dictionary for England described the Great North Road as:

“a fine specimen of the improvements made in public roads in modern times.”

In the 20th century the A1 was conceived as the primary British route linking London and Edinburgh. No longer constrained to visit every town it was never forced to “dog-leg” to York. Like its ancient forbears it followed the direct line through the Vales of York and Mowbray and for much of the distance between Boroughbridge and Scotch Corner it strays only marginally from Roman Dere Street.

Section through Dere Street at Scotch Corner with pre-Roman to Great North Road (Image Credit – NAA)

Dere Street – Milestones and Miscellanea

Two of the three remaining millstone grit “Devil’s Arrows” which stand as high as 6.9m. There may originally have been five of these prehistoric standing stones aligned to point to the crossing point of the Ure near Boroughbridge. They date to the Late Neolithic or Early Bronze Age. Photo Credit – Rex Gibson

Discovered during road building along the line of Dere Street, this milestone once marked the twelfth Roman mile from Corbridge. It has been re-erected close to the road between Corbridge and Risingham.

Divers, come archaeologists (Rolfe Mitchinson and Bob Middlemasswith), with their reconstruction of the early Roman wooden bridge at Piercebridge over the Tees in front of the medieval bridge of 1673 (widened in 1781). Photo Credit – Aaron Watson

Openwork belt mounts were amongst thousands of items recovered from the River Tees at Piercebridge – many of which were probably thrown into the water from the bridge as votive offerings. Many of the items originate from far flung corners of the Roman empire.

The Errington Arms at Portgate is close to the gate through which Dere Street passed through Hadrian’s Wall. An excavation in 1966 revealed the massive masonry foundations of a large military gateway projecting forward from the wall by about 3.6m. Antiquarian records suggest there was a similar projection to the north. The site lies buried just south of the Errington Arms and the nearby roundabout.

A sponsored clock like this one at the Kendal Brewery Arts Centre once stood alongside the Great North Road at Healam Bridge. They were erected in the 1930s alongside a number of major roads. Another Great North Road example was at Alconbury, between Huntingdon and Peterborough.

The 16th century Three Tuns inn (including mounting block) at Scotch Corner crossroads was demolished in 1939 to make way for the roundabout and the Scotch Corner Hotel.

Dere Street (A68) looking north from near Stagshaw Bank near Corbridge (Image Credit – ChronicleLive)

Roman Forts Along Dere Street

The interactive Google map includes brief detail on each of the locations noted along Dere Street but these can be difficult to access on some devices. The content is replicated here.

York (Eboracum)

The Romans built their impressive fortress between the Foss and the Ouse where the minster now stands. It was a major military base with strategically important transport links.

Aldborough (Isurium)

Isurium became a thriving and prosperous Roman town deep within the territory of the Iron Age Brigantes. There was an early fort just to the north-west at Roecliffe where Dere Street crosses the Ure.

Catterick (Cataractonium)

The late first century Roman fort and two later re-buildings were sited on the high ground on the south bank of the River Swale, on the western side of Dere Street. All three were approximately 2ha in area, with the earliest slightly larger. The north eastern quadrants of the forts lie under Thornbrough farm buildings.

Healam Bridge

Recent excavations confirm a roadside settlement though there is still uncertainty as to whether there was in fact a fort as previously assumed.

Piercebridge (Morbium)

The visible remains just north of the river were built in 260AD to control the Tyne crossing. An earlier fort is assumed but has not yet been discovered.

Binchester (Vinovium)

Vinovium was founded around 80 AD and was for a time one of the largest Roman military installations in northern Britain. Originally 7 hectares in size it was large enough to have accommodated several cohorts of legionary infantry and one or more units of auxiliary cavalry. It was reduced to 4 hectares around 160 AD.

Lanchester (Longovicium)

A fort dating from the Hadrianic period, which developed into a small town and industrial complex south west of the modern town.

Ebchester (Vindomora)

The fort is located south of the River Derwent, guarding the crossing point. Almost no remains are visible as the site lies under the modern village.

Corbridge (Coria)

Corbridge is strategically placed beside the lowest fordable point of the Tyne. It marks the meeting point of Dere Street and the east-west route, Stanegate, to the south of Hadrian’s Wall. A series of Roman forts were located here reflecting the strategic priorities of the time. The site is more notable as a site of temples, granaries and workshops.

Risingham (Habitancum)

Situated on a low knoll, surrounded by low ground, above the River Rede. The visible remains are of a fort constructed in the early years of the third century AD by the Emperor Severus; an inscribed slab records the construction of the fort by a 1000 strong mounted cohort.

Rochester (Bremenium)

An important outpost north of Hadrian’s Wall, guarding Dere Street and able to provide warning of attacks from the north. An earlier fort comprising turf ramparts and wooden defences was later re-built in stone. From the west gate can be seen the larger outline of a large temporary camp. Bremenium’s name means “the place on the roaring stream”.

Chew Green

The site includes the remains of two temporary camps, two Roman fortlets, and a Roman fort. The fort is located within the earlier temporary camp. The fort encloses an area of 2.7ha within a rampart 3.6m wide and stands to a maximum height of 3m.

Cappuck

A small fort on the east bank of the Oxnam Water, overlooking the point where Dere Street crossed. There are no visible remains but excavation has revealed a succession of 4 Roman forts.

Newstead (Trimontium)

The fort at the ‘place of the three hills’ became a base for the conquest of the surrounding area. Trimontium is the biggest Roman complex in Scotland. The northernmost amphitheatre discovered in the Roman Empire is visible as a grassy hollow.

Oxton

The fortlet is built alongside Dere Street. There is a long rectangular enclosure with a ditch 3m wide and 225m long, running parallel to the modern A68 road.

Elginhaugh

An early timber-built auxiliary fort on the left bank of the River North Esk to the north-west of Dalkeith. It was thoroughly excavated ahead of construction of the Royal Bank of Scotland Data Centre.

Gogar Green

Two Roman marching camps to the west of Edinburgh.

Camelon

This is where the road from the south reached the Antonine Wall, the first comprehensive border fortification. It is also close to a Roman port on the Firth of Forth. A stone inscription hints that it may have been built by the Twentieth Legion, which was also responsible for the fortresses at Colchester and Chester. There are two adjacent forts and the site included an extensive fortified annexe.