York Minster and the Great North Road

York Minster history spans two millennia and provides direct linkage from Roman times to the present. In that sense its history parallels that of the braid of routes we refer to as the Great North Road.

York’s Minster and its precincts dominate the northern quadrant of the walled city. It is the same space previously occupied by the Roman fortress where, at different times, the sixth and the ninth legions were based. When the mission of St Augustine came to convert England in 597 it carried instructions that the new church was to be governed from the former Roman capitals of London and York.

The great roads such as Ermine Street and Dere Street established by the Romans went on to provide essential lines of communication for the Christian church as it spread and consolidated the length of the country.

York Minster is one of the largest medieval cathedrals in northern Europe and has been visited by those travelling the Great North Road since it was first established. It is located close to Bootham Bar where the road north exits the city but it is not readily visible without making a small diversion.

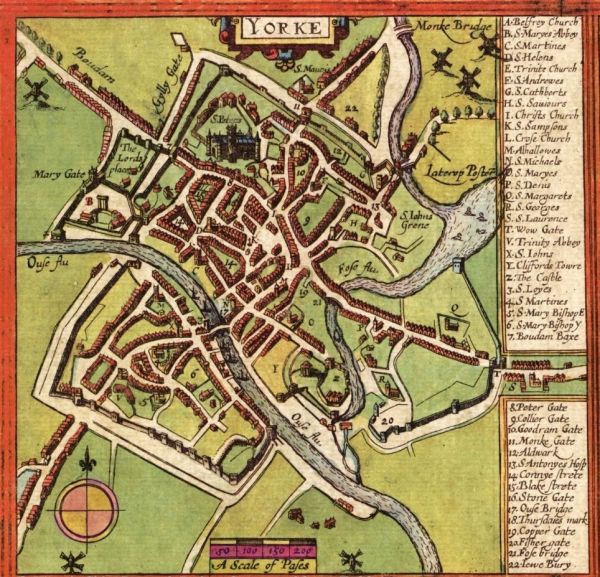

Map of York, Guy Speed, 1611

About York Minster

York Minster’s official name is The Cathedral and Metropolitical Church of Saint Peter. Although a cathedral, it was historically a mission church – spreading the gospel and ministering to the inhabitants of the surrounding region (hence Minster). Unlike many of our other great cathedrals it was never attached to a monastery or abbey, and this was one of the reasons why it was able to transition relatively smoothly at the time of the reformation in the 16th century. Since its establishment, it has been one of the primary centres for the Christian faith in England.

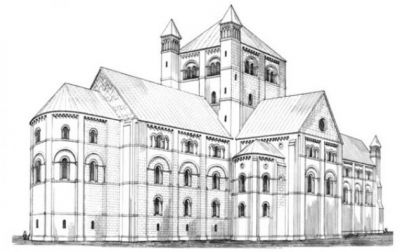

The current Minster was completed in 1472 after several centuries of building. It has a very wide Decorated Gothic nave and chapter house, a Perpendicular Gothic quire and east end and Early English north and south transepts. Of all the Gothic cathedrals of northern Europe only Cologne can compete in terms of scale.

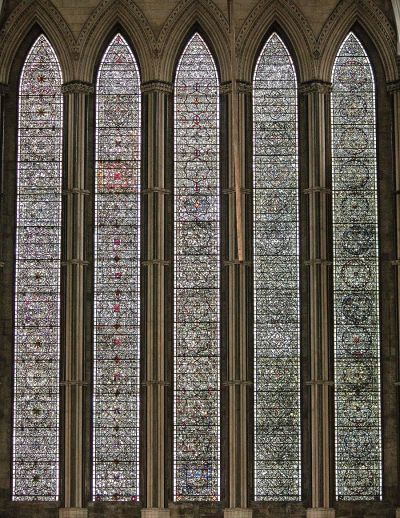

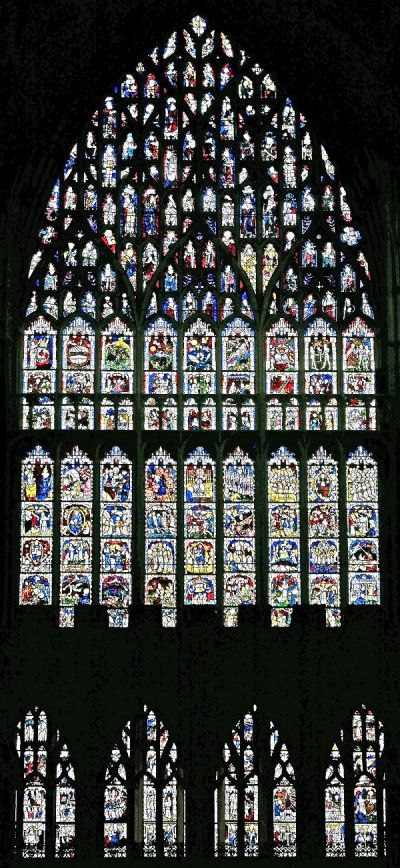

The cathedral contains one of the finest collections of medieval stained glass. Particularly striking are the Five Sisters window in the north transept, the Rose Window in the south, and the Great East Window which holds the largest area of medieval coloured glass in a single window in the world.

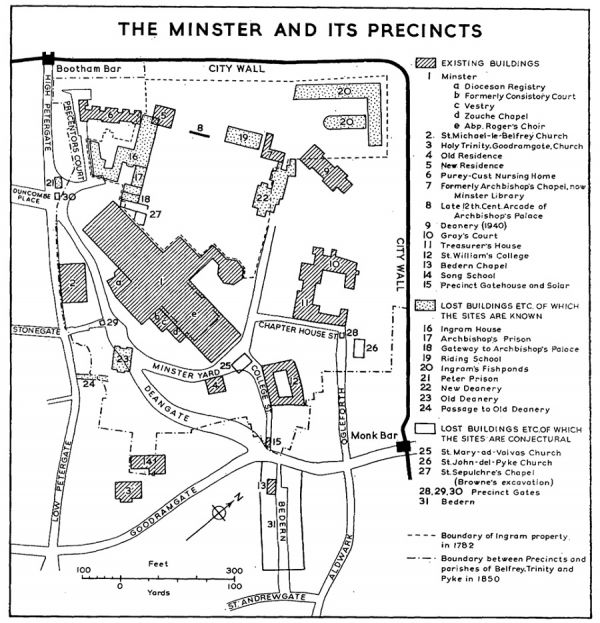

In the past the church sat within its own walled precinct, known as the Liberty of St Peter. The walls around the Liberty were 12 feet high with four gates. A grassed and cobbled precinct lay inside with various residences and official buildings – the Archbishop’s Palace, the Dean’s house and other houses for the Canons, the Treasurer and the Precentor. St William’s College was also within the Liberty and was the home of the chantry priests. This city within a city had its own laws, court, prison and even its own gallows for executions; Peter Prison, York Minster’s jail and gallows, stood outside the West Front, and was used until 1837.

York Minster Precincts (Image Credit – Victoria County History)

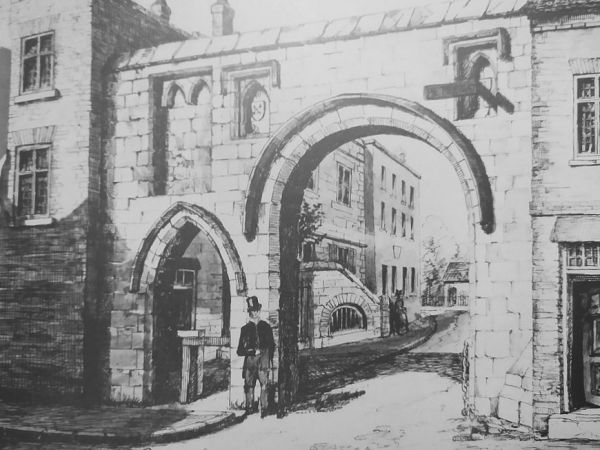

Peter Gate entrance to York Minster Close, built in 1285 and demolished in 1827. (Image Credit – York Art Gallery)

York Minster History – Timeline

Archaeology of York Minster

It is unusual for archaeologists to have opportunities to excavate under churches or cathedrals.

However, in the late 1960s surveys of the Minster’s central tower revealed the 16,000 tonne structure was gradually sinking. This forced a major civil engineering project to strengthen foundations – and the opportunity for archaeologists to explore what lies below.

Basilica wall exposed under York Minster in 1972

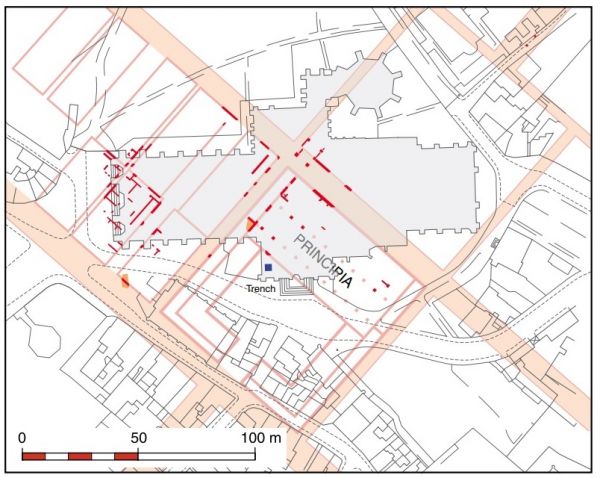

The excavations confirmed the belief that the Minster overlies the Roman barracks of the Roman fortress at Eboracum, originally established in 71AD. A column from the barracks’ Principia (headquarters) unearthed during the excavations has been reconstructed and now stands outside the Minster’s South Transept.

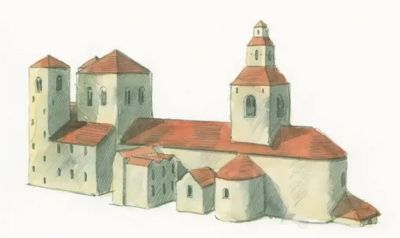

Other finds included evidence of an Anglo-Scandinavian cemetery, and the extensive remains of the Norman cathedral of 1080, the footings and walls of which were reused from 1220 as the foundations of the Gothic arcades in the cathedral we know today. The Norman stonework, designed to bear a much lighter load of completely different geometric properties, failed after nearly 900 years extended service, precipitating the crisis.

A legacy of the underground repairs and excavations was the Undercroft, a space around the foundations left deliberately open beneath the re-laid main floor to make the archaeological remains accessible to the public. A stairwell was dug in the South Transept in 1972, and more recently a lift has been installed, prompting a small additional excavation to a depth 4.2m below the South Transept floor. The work in 2012 provided further glimpses of the site’s history prior to the current minster. Finds included a locally minted silver coin called a sceatta dating from the 9th century, and post holes which could be contemporary with the first wooden cathedral.

Surviving remains of the Norman Minster (Image Credit – www.historyofyork.org.uk)

Roman Principia and nearby buildings and roads shown overlain on modern plan of the Minster area. The 2012 trench in the Minster South Transept is shown in blue (Northern Archaeology Today, Issue 3)

The York Minster Fires

The history of York Minster has been punctuated by major fires. We may think that stone buildings would not be susceptible to fire but in reality an ancient cathedral contains a vast amount of wood.

741

The first stone church was destroyed by fire. Its replacement was completed by 790 when Alcunius, returning from France, seemed most impressed:

“It is very high and supported on solid columns which support recurved arches; beautiful paneling and numerous windows make it shine with the greatest brilliance; its magnificence is further heightened by porticoes, by terraces, and by thirty altars, decorated with a rare variety.”

1069

The Saxon church burns down during the “Harrying of the North” by William I. An army sent by Sweyn of Denmark landed in the north and captured York. A fire lit by the Normans in an attempt to prevent the Danes and local rebels attacking the two castles got out of control and a large part of the city was destroyed including the cathedral.

1137

The whole city of York was burned down due to a fire started by accident, and this badly damaged the minster and other churches. The damage was subsequently made good under the direction of Thomas’s successor, Roger of Pont L’Eveque. The choir and crypt were rebuilt from 1154, and a large chapel dedicated to St. Sepulchre was added to the nave.

1829

An arsonist, Jonathan Martin, concealed himself in the Minster after evensong and succeeded in setting the choir ablaze. The fire was not discovered until the following morning and was not extinguished until the evening of that day. There was heavy damage on the east arm, including destruction of the organ. A public subscription was raised for the repair work and the new choir was opened on 6 May 1832.

Harper describes how Martin fled the scene travelling north:

Meanwhile, the incendiary had fled along the Great North Road; first to Easingwold, thirteen miles away, where he drank a pint of ale; and then tramping on to Thirsk. Thence he hurried to Northallerton, arriving at three o’clock in the afternoon, worn out with thirty-three miles of walking. That night he journeyed in a coal-cart to West Auckland, and so eventually to a friend near Hexham, in whose house he was arrested on the 6th of February. Taken to York, he was tried at the sessions at York Castle on 30th March. The verdict, given on the following day, was not guilty, on the ground of insanity,’ and he was ordered to be kept in close custody during his Majesty’s pleasure.

Jonathan Martin drawn in Goal at York Castle by the Rev J Kilby

1840

An accidental fire left the nave, southwest tower and south aisle roofless and blackened shells. The nave piers were severely cracked and chipped, and the west doors destroyed; the glass, however, was largely preserved. The nave was re-opened after restoration on 15 June 1843.

1909

A small fire in the lower roof of the western aisle of the north transept was quickly extinguished and did little damage.

1984

A lightning strike caused a serious fire in the south transept during the early hours of 9th July prompting firefighters to deliberately collapse the roof of the south transept by pouring tens of thousands of gallons of water onto it. This saved the rest of the building from destruction. The glass of the south transept rose window was shattered by the heat but the lead held it together, allowing it to be taken down for restoration.