Lincoln and the Great North Road

Lincoln was a key staging post for the Romans as they pushed north following the invasion of AD43. It was a focus of the Roman Road network and became the legionary fortress of first the Ninth Hispana (before moving on to York c AD71), then the Second Adiutrix (before moving on to Chester c AD86).

Until the Trent was bridged, Ermine Street from London to York via Lincoln, with the ferry crossing at Winteringham, was the primary land route to the north of Britain. Lincoln grew and prospered. It retained its importance as a regional capital and strategic transport hub through the Anglo-Saxon period. It became one of the 5 fortified towns (“burhs”) of Danelaw. Its Medieval cathedral was physically huge, with ecclesiastical control and influence as far as the Thames.

However, over the centuries, Medieval transport routes evolved; first wooden then stone bridges facilitated more direct north-south roads. Lincoln became something of a back water. In the late Medieval period the prosperous wool trade declined and then in the 16th century dissolution of seven monasteries in the city (as well as nearby abbeys) further diminished the region’s political power.

Lincoln was a destination for stagecoaches from London but it was not on the primary route north.

For these reasons, we will concentrate here on Lincoln’s early history.

Daniel Defoe, rather unkindly observed:

“Lincoln was, London is, and York shall be.”

It actually remains an important and interesting city, well worth the short detour from the A1 or Great North Road as you travel between Stamford and Doncaster. There are plenty of Roman remains to discover, a stunning cathedral, the castle remnants, and the region’s World War II RAF heritage. The Lincoln Museum and Usher Gallery should be one of your first visits.

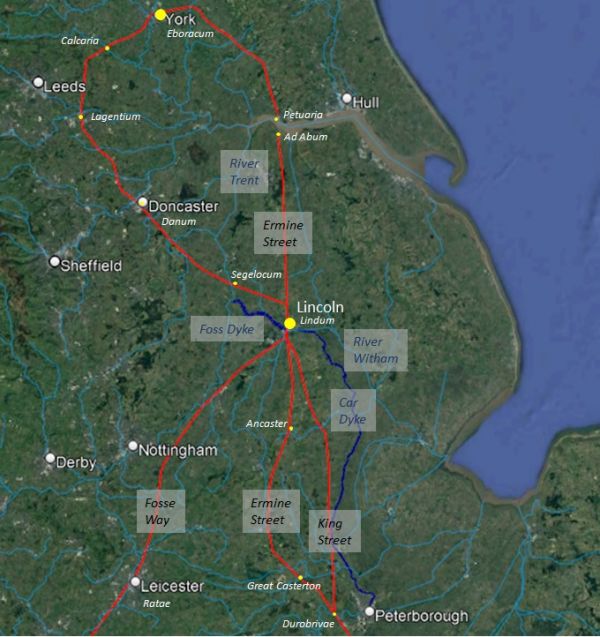

Selected Roman Roads, Roman Dykes & Rivers (superimposed on Google Earth satellite image)

Geography of Lincoln

To understand the early history of Lincoln one needs to be aware of its physical geography. The Roman military base, the Medieval cathedral and castle are all located on high ground immediately to the north of the crossing point of the River Witham. The river was navigable so provided direct access to the North Sea via the Wash. There was a natural widening of the river creating a pool (or Lindo, in Celtic).

The Romans built Ermine Street leading south to Peterborough (Durobrivae), Colchester (Camulodunum) and London (Londinium); and north towards York (Eboracum) via the Humber ferry. An “inland” road northwest to Doncaster (Danum), Castleford (Lagentium) and York branched off Ermine Street a few miles north of the town. The road west was Fosse Way leading to Leicester (Ratae), Cirencester (Corinium Dobunnorum), Bath (Aquae Sulis) and Exeter (Isca Dumnoniorum). Also heading south was King Street (the current A15) reaching Peterborough via Bourne.

Important waterways constructed by the Romans further consolidated the development of the city. The Car Dyke skirted the Fen edge all the way to Peterborough. The Foss Dyke provided inland waterway connections to towns such as York via the Trent.

Even in Roman times the town grew in two parts, the military and administrative centre on the high ground, and the civilian and commercial centre on the low ground by the river. The street connecting the two is aptly name “Steep Hill”.

Roman Lincoln

The Romans arrived in about AD48 and soon built a legionary fortress high on the end of a limestone ridge overlooking the natural lake formed by a widening of the River Witham. When the legions moved north, Colonia Domitiana Lindensium was established to settle army veterans. It was one of four towns in Britain to be granted the status of Colonia, and this new status went on to provide the origin of the place name, Lincoln. The walls of the hilltop fortress were extended down the hillside to the river.

The town prospered and it is thought that the Foss Dyke waterway from the Witham to the Trent was cut in about 120, making it perhaps the earliest canal in the country. During the second century a forum, basilica and public baths were established. An aqueduct was built from Nettleham to bring fresh water to the growing population. The town walls were rebuilt in stone during the third century and when the province of Britannia Inferior was subdivided, Lindum became a regional capital (either of Brittania Secunda or Flavia Caesariensis).

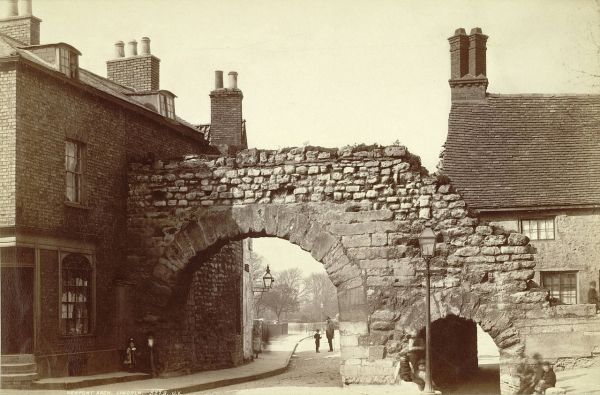

The Ermine Street north gate of the wall (Newport Arch) is reputedly the oldest Roman arch in the United Kingdom still used by traffic. The arch would originally have stood twice as high as it appears today (Image – Postcard c1900)

The “Mint Wall” is a rare survival of a non-defensive Roman wall. Originally 9m high and about 1m thick, it was the north outer wall of the basilica (the Roman town hall and law court). Image Credit – Rex Gibson

Not so “Dark Age” Lincoln

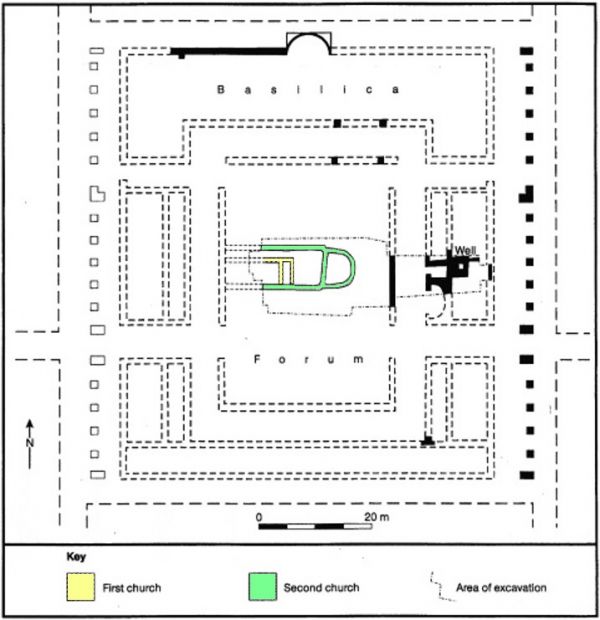

The withdrawal of colonial rule in the early 5th century saw a wind down of Lincoln’s administrative roles and the loss of many of the craft skills which had been associated with a Roman lifestyle. However, it would be wrong to think there was no continuity over the following centuries. Caitlin Green argues persuasively that during the 5th and 6th centuries there was a British regional kingdom based in Lincoln – Lindēs (from British-Latin Lindenses). Parts of the Roman administrative buildings continued to be used – most specifically a church which had been built within the forum. This was rebuilt in the mid-5th century as a larger apsidial, wooden church capable of holding around 100 worshippers. It appears to have survived until as late as 600.

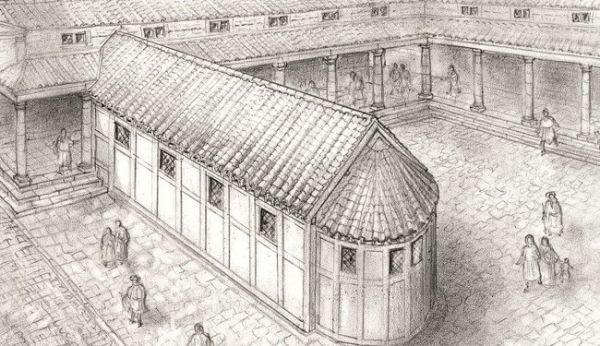

The sequence of buildings at St Paul in the Bail excavated in the 1970s, showing their relationship to the Roman forum. (Image: after Caitlin Green)

The 5th Century Church. (Image Credit – David Vale)

It is likely that there was still a Christian presence at Lincoln when in 629 the pope’s emissary, Paulinus, arrived to consolidate and “regularise” the religion. It is believed that the church of St Paul in the Bail was named after Paulinus. In 653 the Minster church was founded, and it was this which was the precursor to Lincoln Cathedral.

Lincoln continued to be an important regional centre as Anglo-Saxon rule was established, as the region became incorporated into Mercia and as Danish invaders took control. Indeed, Lincoln was at the heart of the Viking Danelaw, a trading centre, and a home to potters, blacksmiths, jewellers and shoemakers. The town even boasted its own mint. Excavations at Flaxengate reveal that an area deserted since Roman times received timber-framed buildings fronting a new street system in about 900. By the mid-11th century Domesday records Lincoln as one of the four largest cities in the country with a probable population of about 6,000 (London’s population was then about 18,000).

The old line of Ermine Street through Lincoln continued to be important as a strategic north-south route. Roman bridges over the major rivers further west would have started to fall into disrepair from the 5th century. It was only from the 9th century that new bridge-building initiatives started to create a more reliable inland road network.

Lincoln’s Medieval Prosperity

Reflecting Lincoln’s strategic importance within the east of England, the Normans wasted no time in investing in the city. Work on the current cathedral was commissioned by William shortly after the invasion. Remigius de Fécamp, the first Bishop of Lincoln, began construction in 1072 and it was consecrated 20 years later. At the end of the 11th century, Lincoln Cathedral was the head of the largest diocese in England – extending from the Humber to the Thames.

Following two centuries of rebuilding and extension (in part necessitated by fires and earthquakes) the cathedral took on a Gothic style of architecture. The central spire was eventually completed in 1311, reaching a height of 160m so displacing the Great Pyramid of Giza as the tallest building in the world. This -remained the case until 1549 when the spire collapsed in a storm.

Lincoln Cathedral owns one of only four surviving copies of Magna Carta, signed in 1215 and brought back to Lincoln by the Bishop of Lincoln.

William ordered the building of Lincoln Castle and new city walls, as part of his strategy to control the rebellious north of the kingdom. Initially of wood, the castle walls were rebuilt in stone in the 11th century. Reflecting the importance of Lincoln and its location on a still much used route north, the castle saw regular royal visitors. In 1141 King Stephen was in fact imprisoned during his war with his cousin Matilda. King Henry II visited Lincoln several times in the late 12th century. King John visited in 1216 (shortly before he died of dysentery at Newark Castle). Edward I visited Lincoln in 1290 as he embarked on Queen Eleanor’s funeral procession to Westminster Abbey. In the early 14th century Edward II and Edward III held parliaments in Lincoln. Indeed Henry VIII came in 1541 with Catherine Howard as part of his “royal progress” to York.

The commercial importance of Lincoln was reinforced when in 1121 Henry I ordered work to make the Foss Dyke Canal navigable again. In 1157 Lincoln received a charter providing more independence for townspeople. From the 12th to the 14th centuries, Lincoln’s prosperity was particularly based on wool which was woven and dyed in the town; Lincoln Green was a famous cloth which benefited greatly from product placement in the Tales of Robin Hood! With trading privileges as a Staple Town (1291) much of the finished cloth was transported along the Witham for export abroad.

Lincoln’s prosperity faded from the mid-14th century. Many died in the Black Death and the population is estimated to have fallen below 3,000. The “staple” was moved to Boston. Navigability of the Witham was impeded by downstream mills. A 1335 commission set up to address obstructions to the Foss Dyke noted that it was:

“so obstructed the passage of boats and ships is no longer possible”.

A new generation of stone bridges over the main rivers (including the Trent at Newark) was taking away any remaining right for Lincoln to be considered to be on the Great North Road.

Lincoln Stagecoaches

Just one topic concerning more recent Lincoln history.

Lincoln maintained sufficient importance to be a significant destination for stagecoaches, including direct services from London which travelled much of the way along the Great North Road.

The Lincoln mail coaches branched at Peterborough, passing through Market Deeping, Baston and Bourne.

The Lincoln Flyer was a famous coach which operated between 1785 and 1871. It had dark- blue painted bodywork with a canary yellow top section and the drivers wore long, yellow waistcoats. It left Lincoln at 2pm, connecting with Stamford and Spalding services at Market Deeping and reaching Peterborough at 9pm; it continued down the Great North Road to reach the Spread Eagle in London at 5am next morning.

Explore Lincoln

More Information about Lincoln

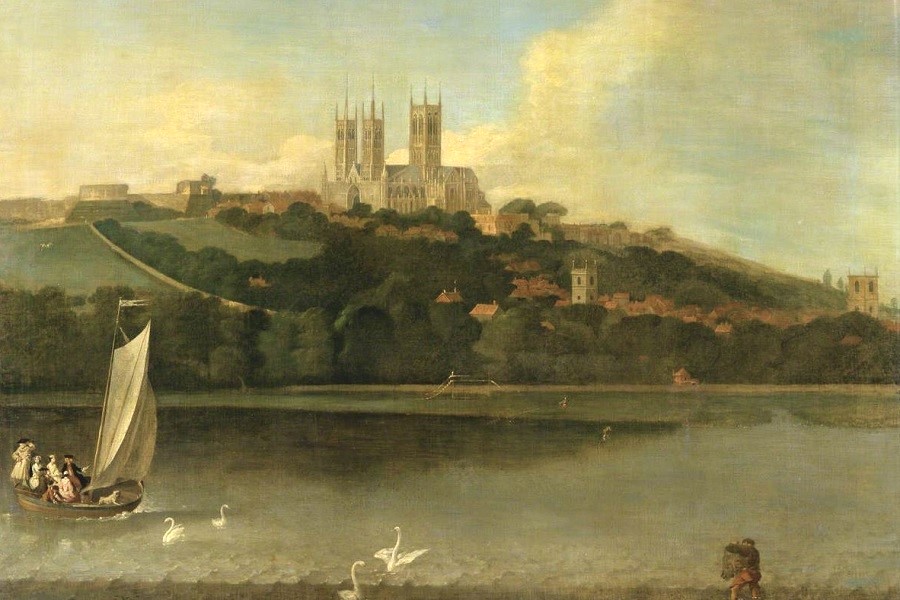

Image at top of page:

A View of the Cathedral and City of Lincoln from the River, Joseph Baker, c1760