Turnpikes and the Great North Road

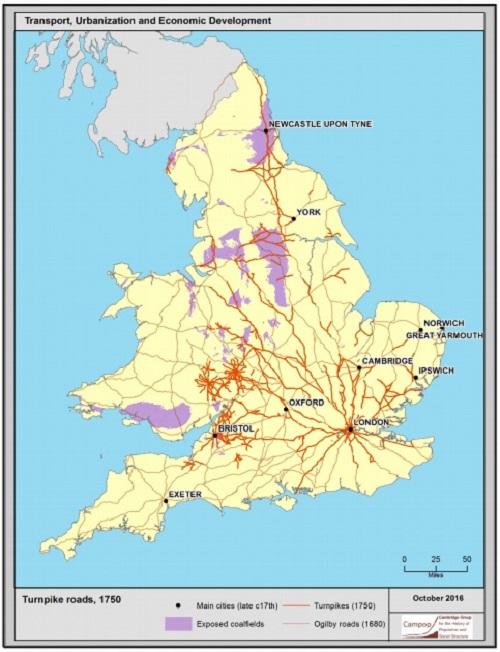

The first turnpike in the country was authorised by a 1663 Act of Parliament and introduced charges to a section of the Old North Road.

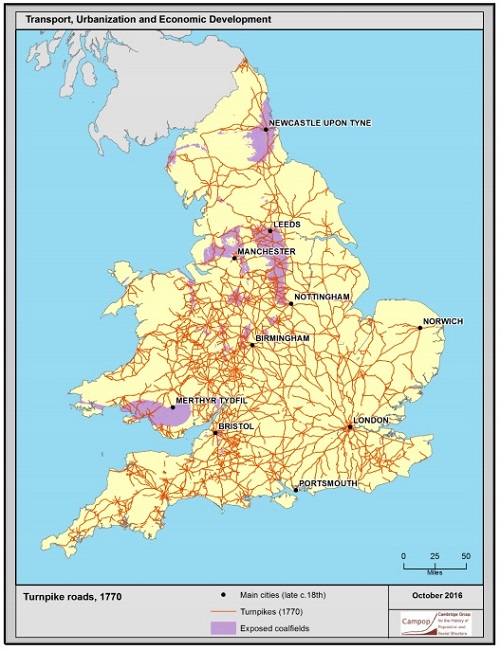

Over the next 100 years turnpikes were introduced the length of the Great North Road from London to Edinburgh stimulating investment and facilitating faster travel. Along with improvements in road building, vehicle design and horse breeding, the turnpikes played a role in growth of the stage-coach network, reduced freight costs and helped underpin industrial growth. They also caused a lot of resentment amongst those forced to pay tolls.

About Turnpikes

Before the Turnpikes

Responsibility for road building and maintenance had been problematic ever since the demise of the Roman model of centralised control and forced labour. It became a very fragmented affair and at various times monarchs had to cajole religious institutions, nobles and local authorities to take action.

A decree by King Aethelbald in 749 insisted that monastic manpower should contribute to building Mercian bridges. It became common for bridges to include a chapel (eg St Ives and Rotherham) where travellers were able to both pray for a safe journey and to make a donation.

Another type of traveller funded road upkeep occurred where an individual adopted a section of road and passers-by provided alms. A formalised version of this practice was applied to the lower slope of Highgate Hill where the north road leaves London. In 1364 Edward III made a decree authorising

“our well-beloved William Phelippe the hermit” to set up a tollbar for the repair of the “Hollow Way” from “our people passing between Heghgate and Smethfelde”.

With dissolution of the monasteries, parishes became responsible for the upkeep of nearby roads. The Statute of Highways in 1555 noted that that the roads had become:

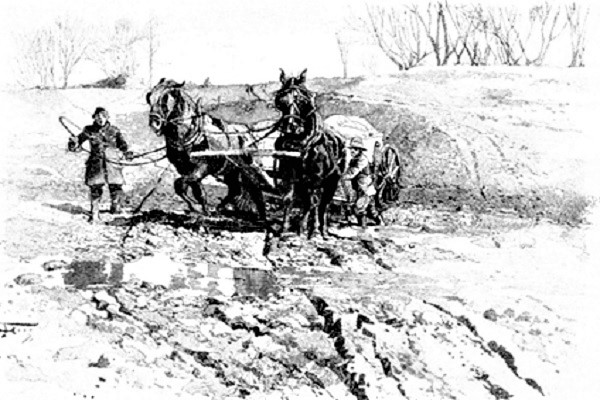

“both very noisome and tedious to travel in and dangerous to all passengers and carriages”

It obliged every parish to elect two honest persons as the ‘Surveyor of Highways’: they were to organise 4 days of maintenance work each year when parishioners were to provide labour and equipment. This obligation was increased to 6 days and ‘statute labour’ remained part of road upkeep until well into the 19th century.

Mud and Pot-holes Create Tipping Point

The inadequacies of the road network became increasingly evident during the 16th and 17th centuries. With a population of 500,000 by 1700, London was a growing metropolis with many of its inhabitants dependent on food, brewers’ malt, fuel and other essentials transported in from the surrounding countryside and country towns. Much of London’s food walked there. Cattle, pigs, sheep and ducks would be driven from as far as Norfolk and Lincolnshire.

At the same time it was becoming more common for people to travel long distance across the country. Ogilby in 1675 published what was in effect the first road atlas. Defoe in the 1720s described his tours through the ‘whole island of Great Britain’.

Travellers bemoaned the trials and tribulations encountered. Coach and wagon operators complained about the constraints placed on vehicle size and wheels to try to protect the roads. Writers compared the country’s roads unfavourable with those encountered in France.

When Samuel Pepys travelled across Finchley Common to visit Barnet Physic Well in 1660 he described the road as:

“only one path and torne, plowed, and digged up, owing to the waggoners carrying excessive weights of over one ton, with more than five horses and oxen to a team”

Defoe notes that, even after the first turnpikes had appeared on the Great North Road:

“There is another Road, which is a Branch of the Northern Road, and is properly called the Coach Road … and this indeed is a most frightful Way, if we take it from Hatfield, or rather the Park Corners of Hatfield House, and from thence to Stevenage, to Baldock, to Biggleswade and Bugden. Here is that famous Lane call’d Baldock Lane, famous for being so impassable that the Coaches and Travellers were oblig’d to break out of the Way even by Force, which the People of the Country not able to prevent, at length placed Gates and laid their lands open, setting men at the Gates to take a voluntary Toll, which Travellers always chose to pay, rather than plunge into Sloughs and Holes, which no Horse could wade through.”

The Turnpike System

Whilst in the 17th century there were growing calls for a system of road building and maintenance financed by road users, the introduction of turnpikes sanctioned by Act of Parliament had a slow start.

In the early 1620s a Bill was presented to relieve the burden on parishes responsible for the Great North Road between Baldock in Hertfordshire and Biggleswade in Bedfordshire by imposing a graduated scale of tolls on various sorts of traffic. The revenue from the tolls was to be employed in repairing the road under the supervision of surveyors or overseers who were to be appointed by the Lord Chancellor and Lord Treasurer, but the form of administration was not precisely indicated. The Bill was defeated.

Finally an Act was passed in 1663 which authorised the justices of the peace in Hertfordshire, Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire to impose various rates of toll on traffic on the Old North Road for a period of eleven years. The preamble of this Act refers to: “the ancient highway and post-road leading from London to York and so into Scotland.” The tolls were set out in the Act:

“for every horse, one penny; for every coach, sixpence; for every waggon, one shilling; for every cart, eightpence; for every score of sheep or lambs, one half-penny, and so on in proportion for greater numbers; for every score of oxen or neat cattle, five pence; for every score of hogs, twopence”

A tollgate was erected at Wadesmill near Hertford though the intended tollgates at Caxton and Stilton were not established at this time.

It was in the 18th century that a fast succession of Turnpike Acts transformed the financing of the road network, each placing operation of the toll roads in the hands of a board of trustees. These ‘turnpike trusts’ were entitled to a share of the statute labour, they had powers of compulsory purchase and they were able to issue bonds to fund investment. The toll rates for each turnpike were regulated according to the type of user: the Mail did not have to pay.

In 1710 a turnpike act introduced new arrangements for Royston to Papworth. Another covered the Alconbury to Wansford. In 1712 a section of the Great North Road from Highgate Gate House, Middlesex to Barnet Blockhouse, Hertfordshire was implemented:

“An Act for repairing the Road leading from Galley Corner adjoining to Enfield Chase in the Parish of South Mims in the County of Middlesex to Lemsford Mill in the County of Hertford…. That for the better Surveying, ordering, repairing and keeping in repair the Road aforesaid … shall be and are here by nominated and appointed Trustees for putting this Act into execution; …”

Many more followed over the next 50 years. Charting the evolution of the trusts can be complex in that each was established for a defined time period (often renewed) but division and modification to the routes covered was common.

Turnpike Trusts Relevant to the Great North Road (after http://www.turnpikes.org.uk)

Following a 1751 Act of Parliament allowing turnpike trusts to be set up in Scotland, the Great North Road was turnpiked from Berwick to Edinburgh in 1753. The ancient route over Soutra via Lauder and Carter Bar was turnpiked in 1768.

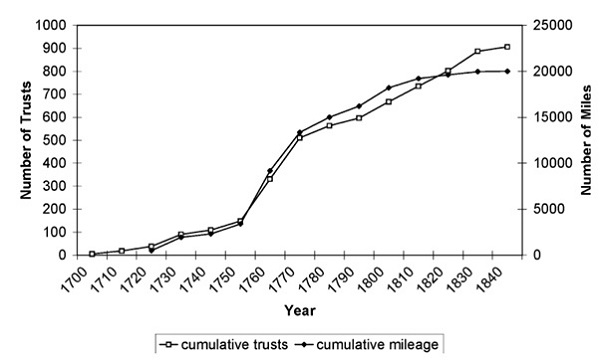

The turnpike system spread throughout the 18th Century, until at their height in the early 1800s, about 1,000 trusts controlled 18,000 miles of road in England and Wales.

The diffusion of turnpike trusts in England and Wales, 1700–1840 (Bogart)

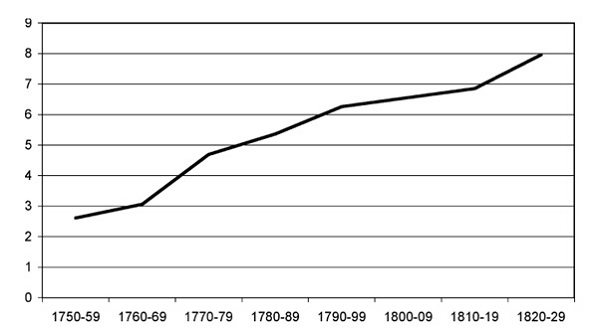

Average journey miles per-hour in passenger services, 1750–1829 (Bogart)

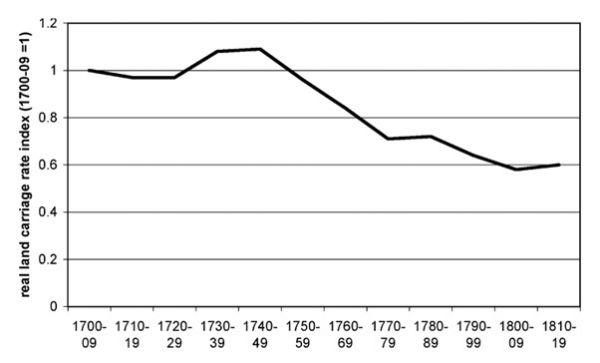

Real land carriage freight rates, 1700–1819 (Bogart)

Generally, the turnpikes did little for the roads through, rather than between, towns. However, Stamford was an exception. Under an act of 1776 the Wansford-Stamford-Bourne trust widened the road through Stamford from the town bridge to Scotgate, replacing the town hall at the trust’s expense.

Reaction to the Turnpikes

Just as the introduction of toll roads or road pricing can be controversial today so there was mixed reaction in the 18th and 19th centuries. Many with an interest in longer distance travel and transport found them a godsend. In his history of inland transport Edwin Pratt recounts a 1745 viewpoint:

In the article on “Roads” in Postlethwayt’s “Dictionary” (1745) it is declared that the country had derived great advantage from the improvements of the roads, and from the application of tolls collected at the turnpikes. Travelling had been rendered safer, easier and pleasanter. “That this end is greatly answered,” we are assured, “everyone’s experience will tell him who can remember the condition of the roads thirty or forty years ago.” There had been, also, a benefit to trade and commerce by the reduced cost of carriage for all sorts of goods and merchandise. On this especially interesting point the writer of the article says: “Those who have made it their business to be rightly informed of this matter have, upon inquiry, found that carriage is now 30 per cent cheaper than before the roads were amended by turnpikes.”

However, there were many complaints about the turnpikes. There was sometimes financial incompetence with virtually all revenue going towards repayment of borrowed money rather than road maintenance. There were examples where the trustees failed to honour their original commitments and acted out of personal interest. The right to collect tolls could be auctioned to the highest bidder creating many opportunities for abuse.

Whitaker in his history of Leeds writes:

“To intercept an ancient highway, to distrain upon a man for the purchase of a convenience which he does not desire, and to debar him from the use of his ancient accommodation, bad as it was, because he will not pay for a better, has certainly an arbitrary aspect, at which the rude and undisciplined rabble of the north would naturally revolt.”

The revolt occurred in 1753. At Selby the inhabitants were summoned by the bellman to assemble at midnight, with hatchets and axes, and destroy the turnpikes. A dozen turnpike bars were pulled down in Yorkshire. When an attempt was made to free rioters being taken to York Castle, troops were called out and several casualties ensued.

There was also resistance to the charges levied by the turnpike and bridges trusts north of the border. In 1791, four tollbars in the Duns area were burned or wrecked.

Naturally, another reaction was to find alternative routes near to the toll road. This was particularly the case for those herding their animals to market; indeed, in some cases this was encouraged in order to reduce damage and congestion. Good examples are the Bullock Road running slightly to the west of the Great North Road on higher ground between Wansford and Alconbury, and the ancient Sewstern Lane between Newark and Stamford.

Elsewhere in the country, dissatisfaction with the turnpike trusts peaked in 1839, when groups of farmers disguised in women’s clothes ripped down toll gates in what came to be known as the Rebecca Riots. As a result, the Turnpikes act of 1844 amalgamated Welsh trusts and reduced tolls.

However, by this time the turnpikes were starting to be overtaken by events. The canals and railways were the new ‘disruptors’ when it came to inland transport. And the piecemeal organisation of the turnpike trusts was failing to maintain and develop the roads needed to serve the ballooning industrial cities.

In the 1850s, trusts were informed that their current Acts would not be renewed. In the 1870s, a process of ‘dis-turnpiking’ occurred – a complex process as many still had debts to pay off. The Local Government Act of 1888 handed responsibility for roads to local councils, with the very last turnpike trust at Llanfairpwll wound up in 1895.

Legacy of the Turnpikes

The turnpikes prompted new roads, bridges, gates and tollhouses. Most of the physical remains of the turnpikes operating the length of the Great North Road have been swept aside by subsequent widening and modernisation. There are a few exceptions still surviving, and a few captured in photographs or pictures.

The old tollhouse at Potters Bar was pulled down in 1897 after one of those new-fangled automobiles smashed into it. Image Credit – Harper

This toll house at Ayot Green in Hertfordshire was lost in the early 1970s. Bought for £250 it was dismantled with a view to reconstruction elsewhere. Its whereabouts is unknown (unless you know better!)

This pillar may have been a 1760s tollgate pier and stands at the corner of a former cross-roads between Markham Moor and Retford in Nottinghamshire. After announcing “London 142 Miles and a half” it reveals that the “The Keys in the Jockey House”. Harper interprets this as a turnpike-gate with no turnpike keeper. The taking of toll seems to have been conducted from the inn. Image Credit – Brian Harris

This toll house three miles north of Doncaster was built in 1832 when the new turnpike road to Selby was established.

One of the other two from this turnpike has been renovated as a home and is commemorated with a Selby Civic Society plaque.

You can stay in this former toll house in Berwick. Dating from about 1840 it oversees both the Great North Road and the road north-east to Duns. It replaced an earlier building demolished to facilitate the railway.

Lamberton toll house was just across the border in Scotland. As with Gretna in the west, Lamberton became a popular destination for young run-away couples wishing to marry without the permission of their parents. (Until 1939 Scottish law required only that boys be at least 12 and girls 14.)

The toll house at Coldstream later became the Bridge Inn. It too was a popular destination for those wishing to escape the English restrictions on marriage.

Approaching Edinburgh from Dunbar you would have passed the toll house at Haddington and in the early 19th century would have received a ticket like this example from the John Gray Centre:

And, of course, the word “bar” occurs regularly in place names. In some cases such as Leeming Bar and Toll Bar (A19 north of Doncaster) in Yorkshire this probably is on account of the toll gate. However, a series in Hertfordshire (Potters Bar, Swanley Bar and Bell Bar) were known long before the turnpike era and probably take their names from forest gates. Dunbar’s name is derived from the Gaelic words for fort and summit.

More Information about Turnpikes

Bogart, Turnpike trusts and the transportation revolution in 18th century England

Bogart, The Turnpike Roads of England and Wales

Pratt, A History of Inland Transport & Communication in England

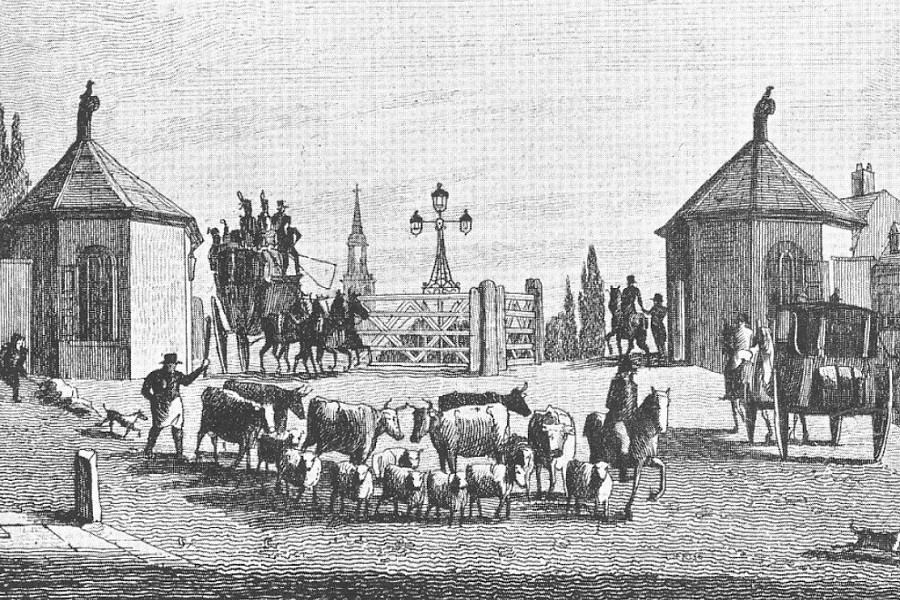

The woodcut print at the top of this article depicts the toll gates near the Angel Inn, Islington, looking north towards the spire of St Mary’s church. Greenwood’s map of 1830 shows the gate close to the later location of the Angel underground station.