History of The Post and the Great North Road

The Great North Road developed during the 17th and 18th centuries as a means of faster and more frequent transport of people and goods, but it was the needs of the emerging postal service that were at the forefront of the drive for faster communication.

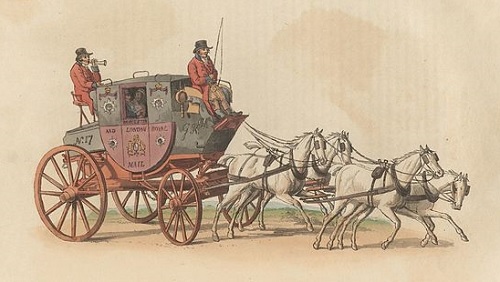

The Post Coach came to epitomise the glamour of the Great North Road. Its distinctive livery dates to the Besant coach of 1787.

Photo Credit – Science Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 DEED

The upper part of the coach was painted black while the door and lower panels were maroon. The Royal Coat of Arms appeared on the doors along with the title ‘Royal Mail’ and the name of the town at either end of the coach’s route. The stars of the four principal orders of knighthood – the Garter, the Bath, the Thistle, and St. Patrick – appeared on the upper panels of the body. The cipher of the reigning monarch was on the front boot, and the number of the coach on the back boot.

History of The Post

The earliest concept of the post was a system where messages could be sent rapidly over long distances by riders on horseback – able to change horses (and sometimes riders) at regular intervals (or “posts”). Such arrangements were used by several ancient civilisations and included the Roman “cursus publicus”.

Once the Romans had left Britain such communication was less structured though of course when required King’s despatches would be carried by King’s Messengers. The history of the post perhaps begins when Edward IV set up relays of horsemen to speed the progress of royal correspondence. Then in 1512 Brian Tuke, a secretary to Cardinal Wolsey, was paid £100 as “Master of the Posts”. The role of “Governor of the King’s Posts” was established in 1517. [This was a precursor to that of “Postmaster General” which remained a senior political role until 1969.]

For the exclusive use of the Royal Court, relays of horses and messengers were to be maintained on important routes. The citizens along the route could be compelled to provide horses and were compensated by a payment, typically of 1d per mile. Over time the carrying of private mail was also permitted so long as the royal mail took precedence.

Charles I founded the ‘Letter Office of England and Scotland’ in 1635 opening his postal service to the public. The primary routes included the post roads radiating from London to Edinburgh, Holyhead, Dover, and Plymouth.

a running post or two, to run night and day, between Edinburgh and London, to go thither and come back again in six days.

At this time, riders on horseback still carried the mail. Dirt roads were in notoriously poor condition – hard on the men and horses. The post-boys in scarlet livery travelled little more than three miles per hour. At each post letters were delivered to the local postmaster, who removed those for the area.

In 1660 came an Act of Parliament for Erecting and Establishing a Post Office. The objective was to co-ordinate and control the emerging public and private postal arrangements – effectively as a state monopoly with postage charges a form of taxation. There was a basic rate of two pence for distances under ‘fourscore English miles’ and three pence for greater distances. The Act made direct mention of the north road:

And for the port of every Letter not exceeding one sheete from London unto the Towne of Berwicke or from thence to the Citty of London Three pence of English money,

The frequency and speed of the London to Edinburgh service prompted criticism over the coming decades though at times the demand was not high. One day in 1745 just one letter was delivered to Edinburgh (for the British Linen Company); and on another day in the same year only one was despatched to London (for Sir William Pulteney, a banker).

An Edinburgh merchant, George Chalmers, pushed for improvements to the Great North Mail in the 1760s. The coaches started to bypass York using the alternative Boroughbridge route; a service was run 6 days per week; stop-overs at various towns were accelerated. The planned journey times were reduced to 82 hours northbound and 85 hours southbound.

In 1782 John Palmer, a Bath brewer and theatre owner, made recommendations for the improvement of postal services. Palmer’s plan was to convey the mail by stage-coaches in the same way that people and packages were delivered. The coaches were to be guarded by men armed with blunderbusses to ensure their safe arrival. The first mail-coach ran on the Bath Road in August 1784, and its success was so great that other towns lobbied for similar services. York came next with a mail coach put on the road between London, York, and Edinburgh in October.

The mail coach, horses and the driver were all provided by contractors. From 1787 a patented coach design was mandatory. Each morning, when coaches reached London they were taken to a constructor’s works, to be cleaned and oiled. Passengers travelling long distance from London would gather at one of the coaching establishments (most likely the Bull and Mouth Inn for those travelling the Great North Road). To catch the coach they then had to make their own way to the Post Office Headquarters in Lombard Street. From there all mail coaches departed promptly at 8 pm, and to keep to this schedule the Post Office had to close by 7 pm to enable sorting of the mail for the various routes.

Guards were employed by the Post Office, receiving a generous 10s 6d per week and a pension, in order to deter theft and corruption. They were supplied with a 3 foot long horn used to announce imminent arrival at post houses so that postmasters would have the mail ready for collection; to alert tollgate keepers to open the turnpike gate before the coach got there (a 40 shillings fine was payable if not); and to alert innkeepers to prepare refreshment for hungry travellers.

Play the Post Horn Gallop!

As the coach travelled through towns or villages where it was not due to stop, the guard would throw out the bags of letters to the Letter Receiver or Postmaster. At the same time, the guard would snatch from him the outgoing bags of mail.

Guard, Moses Nobbs, served for 55 years (1836-1891) on coaches and later on trains.

William IV Royal Mail Coach Guards flintlock pistol inscribed around the muzzle ‘For His Majesty’s Coaches’ (1835)

Four passengers were carried inside the mail coach but later one more was allowed to sit outside next to the driver. The number of external passengers was increased to three with the introduction of a double seat behind the driver. No one was permitted to sit at the back near the guard or the mail box. The mail coach travelled faster than the stage coach but whereas the stage stopped for meals where convenient for its passengers, the mail coach stopped only where necessary for postal business. The contractors organised fresh horses at stages along the route, usually every 10 miles.

Speeds started to improve once the innovations of Telford, MacAdam and others began to improve surfaces, reduce inclines and improve bridges.

Letter Carrier’s Uniform introduced in 1793

The General Post Office in London was relocated to larger premises at St Martin’s le Grand in 1829. Designed with Grecian ionic porticoes by Sir Robert Smirke, it was 400 feet long and was lit with a thousand gas burners at night. By this time 28 mail coaches were leaving London simultaneously at 8pm for all parts of the country. [The print of the General Post Office at top of page is by James Pollard, 1830.]

In 1839 a system of uniform penny postage was proposed by Rowland Hill. Franking was ended and senders of letters were charged by weight at a standard rate regardless of distance. The first adhesive postage stamp, the Penny Black, came in to use in 1840. Already by this time post was started to be transported by train. The last regular London based coach service was the London to Norwich, ending in 1846.