Edinburgh Castle and the Great North Road

Edinburgh Castle is the northerly “bookend” of the Great North Road as St Paul’s Cathedral is in the south. Not strictly on the road but both ancient, striking landmarks, visible from distance, which scream “you’ve arrived”.

The city of Edinburgh grew up around the Castle, crammed, until the late 17th century, within its late medieval walls. Travellers complained about the seedy coaching inns squeezed within the old town. The city has expanded repeatedly since then but the castle, perched on its 130m high volcanic rock continues to dominate the Scottish capital.

Edinburgh Castle was for many centuries at the heart of royal and military power in Scotland. It bore a significance even beyond its striking location as the pendulum of co-operation and conflict between England and Scotland swung back and forth.

The castle has marked the start point or destination for numerous kings, queens, courtiers and commanders who have journeyed the Great North Road over the last 1,000 years.

Lament for Iolaire

A lone piper in the distance (the best way to listen to bagpipes) plays a pibroch in memory of dead comrades-in-arms.

About Edinburgh Castle

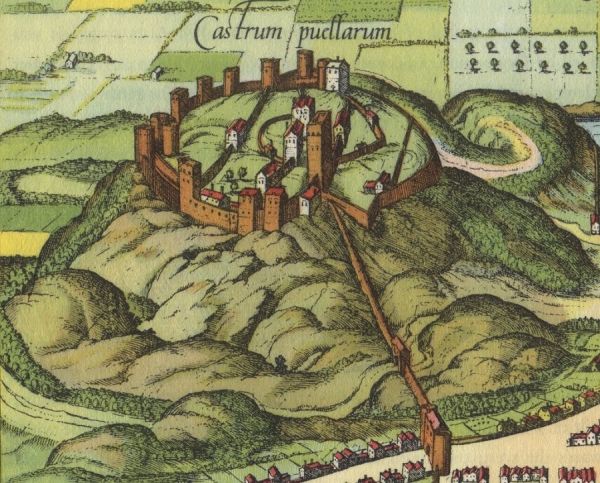

Legend and early chronicles suggest the “Maidens’ Castle” was founded by Ebraucus, King of the Britons, in the late 10th century. The facts and the meaning of the “Maidens’ Castle” name are unclear. It may be that the initial building was a monastery.

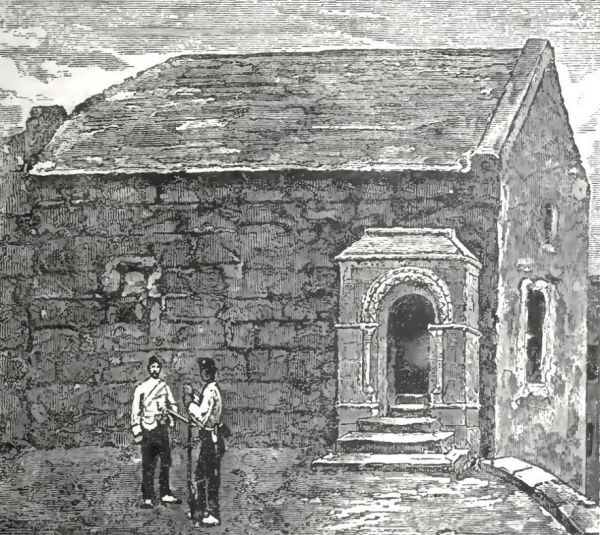

The oldest surviving building on the site is the 12th century St Margaret’s Chapel. This was established by King David I in memory of his mother, Margaret of Wessex. Her brother had been positioned to follow Harold upon his defeat at Hastings; instead he succumbed to the inevitable and moved with other family members to Scotland. Margaret married Malcolm III of Scotland; their children included two Scottish kings, Alexander I and David I, as well as Matilda, Queen of England.

Saint Margaret’s Chapel depicted in Agnes Strickland’s Queens of England, 1882

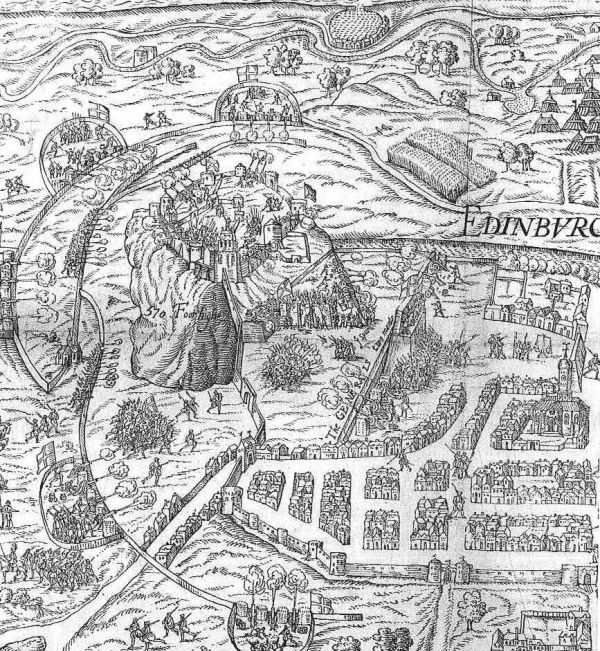

It was only when Edward I arrived in 1296 that Edinburgh joined the ranks of the classic medieval castles designed by invaders to subjugate local opposition. Edward had recently constructed a series of castles in North Wales to consolidate his victories there. He took the same approach in Edinburgh, calling on the very same masons and project managers, to re-model the Castle. By 1300 a large garrison had been installed though English control was short lived.

Edinburgh Castle retained its combined role as royal residence, seat of government and military fortress through the next 150 years. By the late 15th century monarchs were preferring to spend time at the more spacious Abbey of Holyrood, and between 1501 and 1505 King James IV built Holyrood House as his primary residence. However, during turbulent decades which followed, important royals remained at the Castle; these included Mary Queen of Scots whose son James, born there in 1566, would later be King of both Scotland and England. James made a triumphant journey south along the Great North Road in 1603.

The Castle’s role as a fortress continued though the primary source of attack switched from the English to the Jacobite Highlanders. A full-time garrison was maintained at the Castle until 1923.

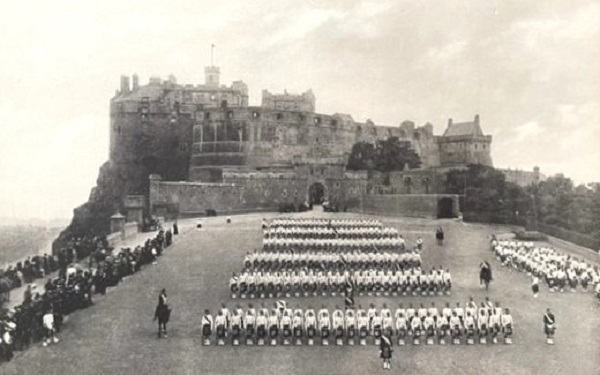

The military tradition lives on with the nightly “tattoo” held every evening in August – helping to make Edinburgh Castle one of the five most popular paid tourist attractions in the UK.

Massed Pipes and Drums at the Tattoo (Image credit – The Royal Edinburgh Military Tattoo)

The Edinburgh Castle Landscape

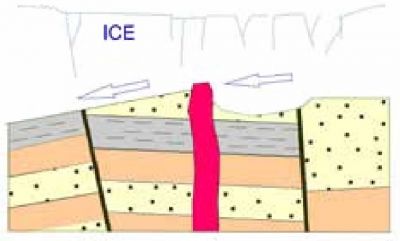

The Castle Rock in Edinburgh boasts excellent visibility of the surrounding landscape, and steep defensive natural walls on three sides. To the east, there is the gentle slope of today’s Royal Mile from the Castle to the Canongate. To the geologist it is a fine example of a “crag and tail” formation. A 300-million-year-old vertical, volcanic plug of dolerite has withstood the erosion of surrounding and overlying sedimentary deposits by glacial flows from the west. (Similar volcanic origins explain nearby Arthur’s Seat and Carlton Hill.) Whilst the topography may be good for defence, the impervious rock has made supplies of water a challenge during the Castle’s many sieges, despite deep wells.

Image Credit – Edinburgh Geological Society

To the north of the Castle Rock the glaciers had left behind a marshy area with small lakes. Under the orders of King James III, the stream running through this swampy vale was dammed in 1460, creating the “Nor’ Loch” to strengthen the castle’s defences.

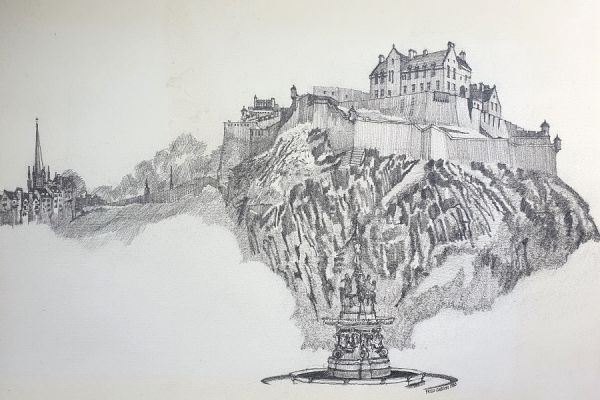

Picturesque from a distance as imagined in 1824 by Alexander Nasmyth (top of page), the Nor’ Loch became an open cess pit and was the scene of brutal punishments such as the “dooking” of witches in the early 17th century. The regular stench emanating from the loch brought increasing demands for change as the Georgian New Town was laid out and the North Bridge built to connect the new and old. In place of the Nor’ Loch, the Princess Street Gardens we know today were developed in stages, east to west, between 1830 and 1876.

Edinburgh Castle History – Timeline

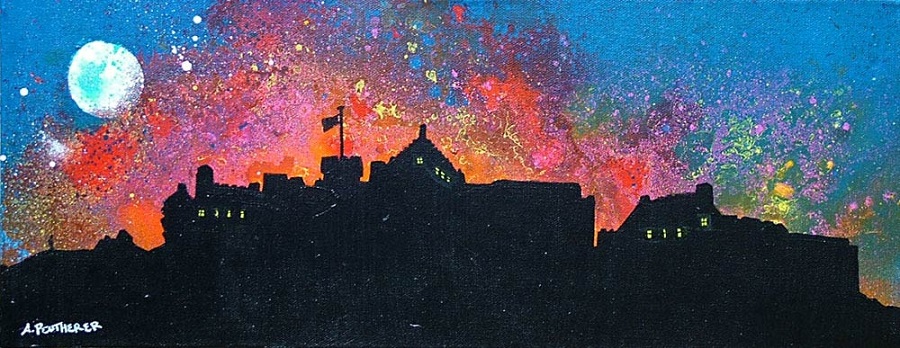

Edinburgh Castle Fireworks by Scottish landscape artist Andy Peutherer

Mons Meg

The Mons Meg medieval cannon encapsulates a good deal of Edinburgh Castle history.

The 6-tonne siege gun was one of a pair given to James II in 1457 by Duke Philip of Burgundy, taking the name of Mons from the Belgian town where they were made. (The affectionate “Meg” was added much later.)

Image credit: Edinburgh Castle

The canon could fire a 150kg stone projectile 2 miles. 15th century outings included attacks on Dumbarton and Threave castles, while in the 16th century it was used by James V’s navy. During the celebration of the marriage of Mary Queen of Scots a cannonball fired by Mons Meg landed in what is now the Royal Botanic Garden. The barrel finally burst in 1681 firing a salute to mark a visit to Edinburgh by James, Duke of York (the younger son of Charles I, and future King James VII & II).

The canon went on to spend 75 years in London but was returned to Edinburgh Castle in 1829 following a campaign by Sir Walter Scott, amongst others. Transportation of course was by ship rather than the Great North Road! It now resides on a terrace in front of St Margaret’s Chapel at the highest point of the rock.

More Information about Edinburgh Castle

Edinburgh Castle from Princes Street Gardens, Fred Gibson, 1980