St Paul’s Cathedral and the Great North Road

Saint Paul’s Cathedral is not “on” the Great North Road – more one of its “bookends”, as Edinburgh Castle is in the north. However, whether you define the London end of the road as the General Post Office, or as the start point of the A1, or as the Roman forum from which Ermine Street headed north, the site of the great St Paul’s is close by. And it has been there for 1,400 years – the enduring London landmark.

About St Paul’s Cathedral

Everybody knows St Paul’s. Some have had the opportunity as a child to climb 365 feet to the golden ball to wonder at the view from the very top. Here, we will concentrate on the succession of buildings which have occupied Ludgate Hill, the highest point of the City of London.

Before 604

All those who delve into history will recognise the tendency for people to build upon the beliefs, culture and physical landscape they inherit. Not surprisingly, early antiquarians assumed there would have been religious use of the site dating back to the Roman Christian era or beyond. There is in fact no documentary evidence for this and indeed in the 17th century during construction of the current building Wren noted the absence of any remains to support this theory.

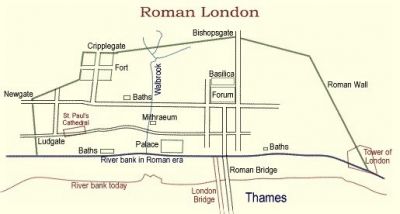

The original Roman settlement with its forum and basilica was to the east of the River Walbrook, close to the current Bank of England. During the second century the town spilled out to the west and the wall constructed in about 200 incorporated the site of the later cathedral. It would have been to the south-west of the amphitheatre and south of the legionary fortress at Cripplegate. The finds in the St Paul’s area include tessellated floors and heating systems probably associated with residential buildings.

604 to 1087

The first St Paul’s cathedral was established in the early 7th century, following the mission of St Augustine instigated by Pope Gregory the Great. It is said that the church was founded in 604 by Saint Mellitus who travelled with Augustine. In 675, Saint Erkenwald (Abbott of Chertsey) was consecrated as Bishop of London.

The original church buildings would have been predominantly of wood and they were destroyed a number of times by fire and Viking attacks.

1087 – Old St Pauls

The Norman invasion stimulated a wave of new religious houses and the rebuilding of churches in stone. Bishop Maurice, Chaplain to William the Conqueror, started on a new cathedral in about 1087. The first phase became available for religious use in 1148. This gothic building came to define London for over 500 years.

St Paul’s in 1540. A 19th century engraving from a painting by Wyngarde made for Philip II of Spain.

Old St Paul’s was the largest building in the country, 178m long and 88m wide across the transcepts. Until surpassed by Lincoln cathedral its 149mm spire was the tallest. Unfortunately, the spire suffered a lightning strike in 1561 and was never replaced.

During the reformation of the 16th century, shrines were desecrated and images were removed but the building itself was largely unscathed. That’s more than can be said for the first protestant Bishop of London who was martyred by Mary I before the Book of Common Prayer was consolidated under Elizabeth.

In the 1630s Indigo Jones was commissioned to undertake a major restoration of the, by then, somewhat dilapidated cathedral structure. A new west front was added but further work was interrupted by the outbreak of the Civil War in 1642. It was not until the 1650s that attention returned to the serious state of disrepair. Inspired by his knowledge of French and Italian architecture, Christopher Wren proposed the addition of a dome to the medieval structure. Agreed in August 1666, the plan was overtaken by events. Only a week later the Great Fire of London reached St Paul’s, which at the time was surrounded by highly combustible wooden scaffolding.

The high vaults fell putting in train ambitious plans for a more radical replacement. The brief from the Archbishop of Canterbury was a cathedral that was:

“Handsome and noble to all the ends of it and to the reputation of the City and the nation”

1675 – New St Pauls

The design evolved through a range of 5 concepts – the third of which was encapsulated in the detailed “great model” of 1673, which still survives. Wren was steered back towards a slightly more conventional style in the approved baroque design – but retained considerable discretion allowing further substantial changes during the course of the project. Today we might call this process “agile”.

Construction commenced in 1675; the first service was held in 1697; the last stone was laid in 1708; and the topping-out was in 1710. It was an impressive tribute to Sir Christopher Wren: architect of the cathedral and a leading scientist and mathematician of his day. The total cost was well in excess of £1m.

St Paul’s in 1754. Like the image at top of page depicting Lord Mayor’s Day in 1746 this painting is by Canaletto.

The new building was not without its problems. Cracks had been seen before its completion and in the 1920s concerns grew. The cathedral was closed for 5 years whilst piers and the dome were strengthened. The structure was then tested during the Blitz when it received two significant bomb strikes. The surrounding area was devastated but the cathedral stood strong.

More Information about St Paul’s Cathedral

Top of page image: Canaletto, The River Thames with St. Paul’s Cathedral on Lord Mayor’s Day