Markham Moor Service Station and the Great North Road

Few 20th century landmarks along the Great North Road are as distinctive as the concrete roofline of the former petrol filling station at Markham Moor. For visual appeal it ranks alongside the Bauhaus building at Wansford and the Angel of the North at Gateshead.

It was constructed in 1960 as the canopy for a National Benzole filling station which operated on the site until the late 1980s. It was then developed into a hard to miss Little Chef restaurant. It currently operates as a Starbucks. There are many aspects of its design, evolution and survival which are worthy of note. In 2012 it was designated a Grade II listed structure.

The building is located alongside the southbound carriageway between Doncaster and Newark, close to the junction with the A57 heading east to Lincoln.

About Markham Moor Service Station

In the late 1950s National Benzole decided they would benefit from a premium forecourt to reflect their premium brand (later subsumed within BP).

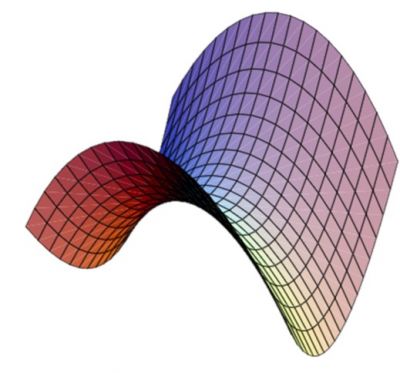

They instructed Lincoln based architect, Sam Scorer, to come up with a one-off design. Drawing on the expertise of his structural engineer, Kalman Hajnal-Kónyi, the design used a minimum of steel and instead derived its strength from carefully configured site-poured concrete. The double curved, saddle shaped shell is known as a hyperbolic paraboloid. The same strong shape is a patented feature of the Pringle fabricated potato chip.

The apexes of the roof are 11.3m high; its low points are only 1.5m off the ground; the shell is just 75mm thick.

In 1989, the filling station beneath the roof was removed and a Little Chef roadside restaurant inserted beneath the canopy.

Markham Moor Little Chef (Image Credit – Karolina Szynalska)

In 2003, plans were announced to demolish the building to facilitate a much-enlarged road junction. There was vociferous opposition and the proposed junction was re-positioned. In 2012 the Little Chef closed. By this time the structure was showing its age and was in need of some loving care and maintenance.

Derelict in the 2010s (Image Credit – Historic England)

Help was a while coming but in 2019 Starbucks acquired the site. The structure’s unique appeal to passing motorists ensured it could deliver again for yet another roadside business.

The Markham Moor wing’s latest incarnation (Image Credit – Otis Gilbert)

Who was Hugh Segar (Sam) Scorer?

Portrait of Sam Scorer by his friend, Tony Bartl

Sam Scorer led an interesting and varied life. He:

- was an artist

- studied Mechanical Sciences at Cambridge in the early 1940s

- became a pilot during the war

- crashed while landing on an aircraft carrier in the Baltic

- studied architecture

- was a motor racing enthusiast

- owned Jags and other fast cars with the plate EVL 1

- became Lincoln City Sheriff

- drove a caravan to Italy for earthquake victims

As a Lincoln based architect he was responsible for designing several local schools during the 1950s and the city’s first multi-storey car park in 1970. However, it was his fascination with the hyperbolic paraboloid that earned him the distinction of having three of his buildings listed. Scorer worked with structural engineer, Kalman Hajnal-Kónyi who had arrived as a refugee from Hungary in the 1930s. Thin shell concrete roofs had been pioneered in Germany before the war and Hajnal-Kónyi helped popularise the technique in Britain.

1959 Lincolnshire Motor Company Showrooms -now housing Brayford Pool restaurants (Image Credit – Scorer Hawkins Architects)

St John the Baptist’s Church, Ermine, Lincoln, built in 1963 (Image Credit – Jules & Jenny)

What’s a Hyperbolic Paraboloid Shell

A hyperbolic paraboloid (or “Hypar”) is a doubly-curved surface that that has a convex form along one axis, and a concave form along the other. Every point on its surface lies on two straight lines across the surface; horizontal sections taken through the surface are hyperbolic in format and vertical sections are parabolic.

Hyperbolic paraboloid shells derive their strength from their unique shape rather than their mass, enabling remarkably frugal use of materials. Braced in two directions they achieve exceptional stiffness and withstand both dead and dynamic loads. The same shell serves both as roof and load bearing wall.

A hyperbolic paraboloid shell can be constructed in many materials including wood and steel, but in the mid-20th century it was concrete which generated much interest. The ability to use innovative design to economise on scarce materials following World War II was a particular driver.

There are many examples of the technique being used in architecture though the added complexity of integrating non-linear shapes with other architectural elements mean they are, today, more likely to be used for design aesthetics rather than economy.