Stage-coach History and the Great North Road

Stage-coach history is intertwined with societal changes in travel habits, technical innovation, the roots of industrial revolution, population growth and urbanisation. It’s a story with roots back to the 16th century, a slow build, an intense crescendo, and a sudden demise.

One of the very first regular stage-coach services operated along the Great North Road.

Stage-coaches came to embody the thrill and excitement of high-speed travel in the 17th, 18th and early 19th centuries. They facilitated the union between Scotland and England. They connected the great metropolis of London with the newly industrialising regions of the north, and the ports leading to new colonies. They spawned numerous hostelries – some of which survive to this day. They generated legends and nostalgia which permeated the national culture and literary record.

The first stage-coach between London and York ran in 1653. A fortnightly connecting service to Edinburgh started in 1658. The Edinburgh fare was £4, and the journey time might be 10 days or more.

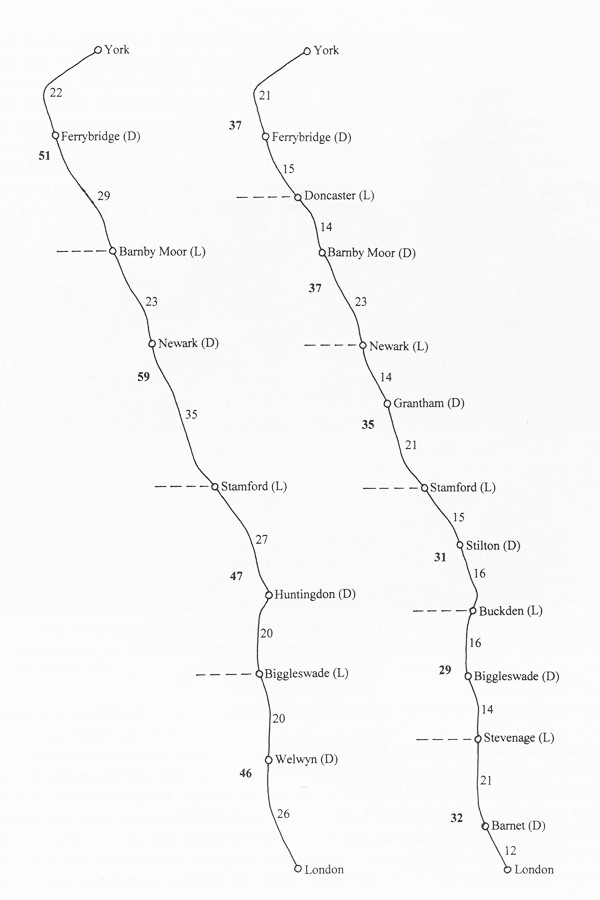

Early itineraries did not always match those advertised and it is necessary to cross check against the diary records of travellers. The maps below record the late 17th century lodging (L) and dining stops (D) of the York coach in summer (left) and winter (right).

Image credit: Gerhold, The York stage-coach, Map 14

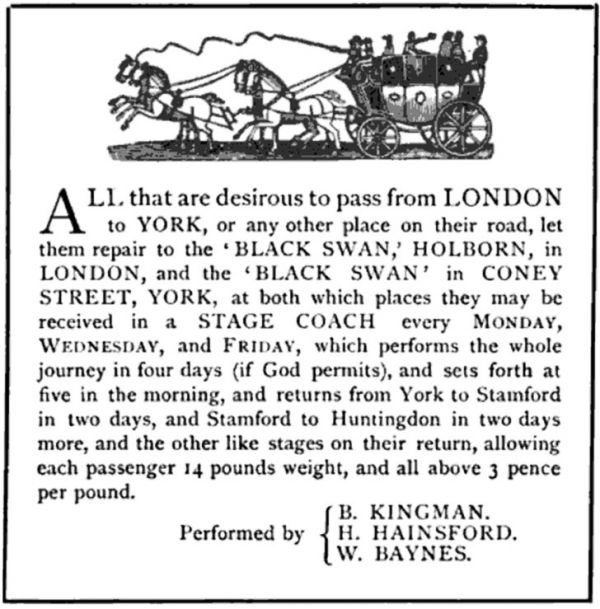

The 1706 announcement below is for a 4-day service to York, running between the Black Swan in Holborn and the Black Swan in York.

Journey times along the Great North Road did not change much during the early 18th century, and the number of services was very limited. In 1734 a weekly coach from Edinburgh to London was announced.

“A coach will set out towards the end of next week for London, or any place on the road. To be performed in nine days, being three days sooner than any other coach that travels the road: for which purpose eight stout horses are stationed at proper distances.”

There were signs of change from the mid-18th century. A 1754 advertisement in the Edinburgh “Courant” announced Hosea Eastgate’s “genteel glass coach”, though the journey time remained leisurely:

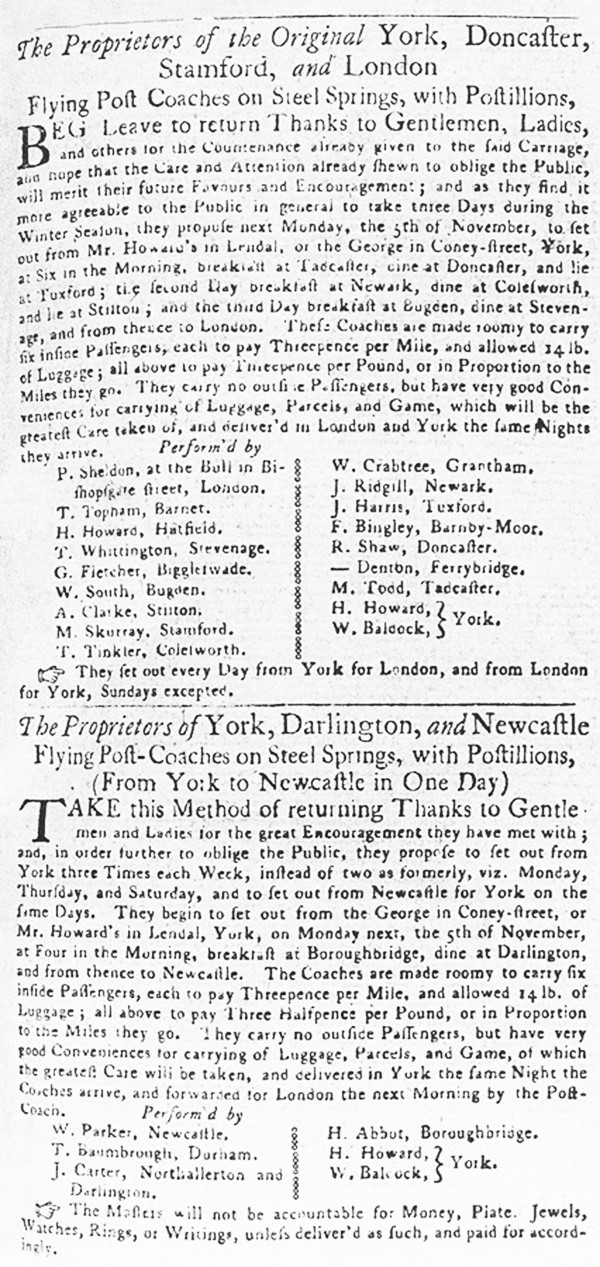

A 1764 advertisement for premium “Flying” York and Newcastle post coaches emphasises steel springs and a winter journey time of just 3 days to York and a further day to Newcastle:

The next 60 years represented the high point of stage-coach history along the Great North Road. The post office adopted coaches; services multiplied; journey times tumbled; coaching inns proliferated.

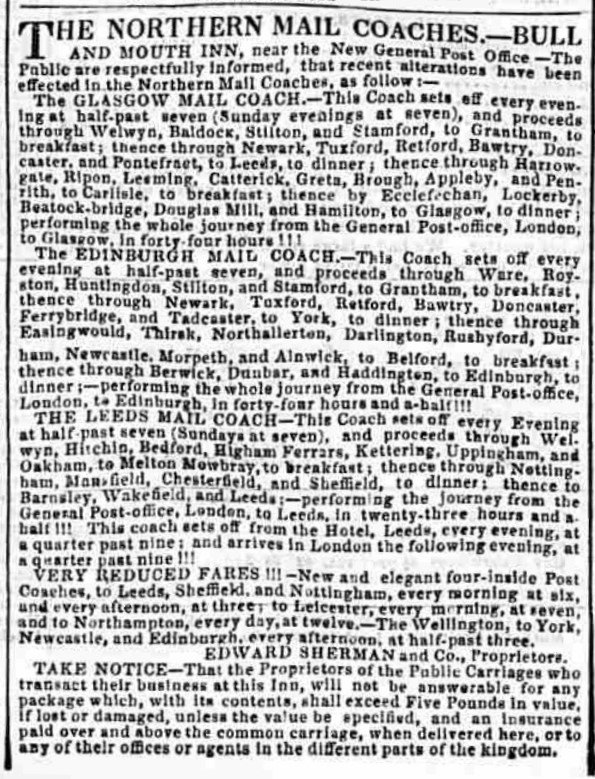

Larger coaching companies emerged, marketing comprehensive services to multiple destinations. Competition intensified, with a mix of large coaches focusing on the lowest possible fare, and high speed services emphasising short stages and small passenger numbers. Sherman’s advertisement below appeared in May 1827 in the London Morning Herald; the total journey time is down to 44.5 hours!

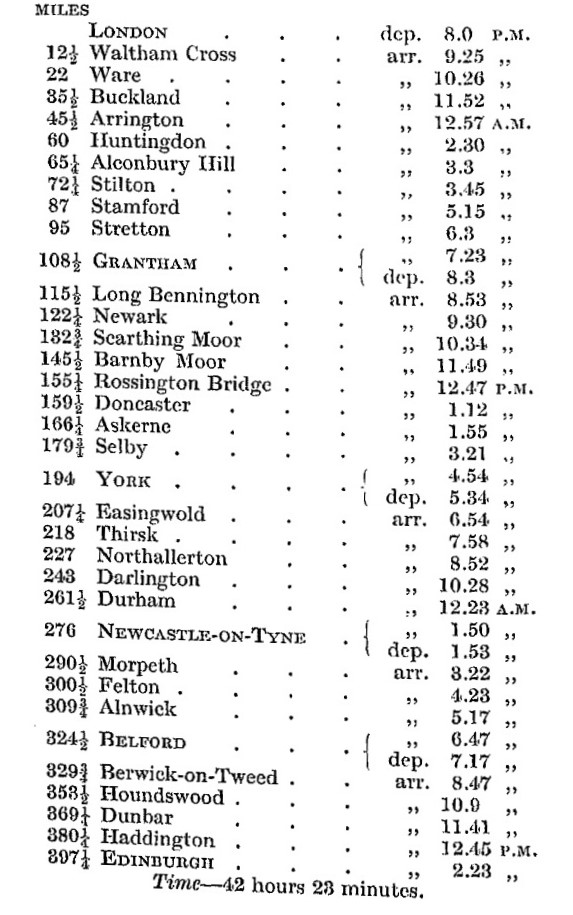

The 1832 mail coach was scheduled to take 42 hours 23 minutes:

Source: Harper Great North Road

In 1840 the first train ran direct from York to London; by the 1850s, there were 13 trains a day between the two cities, carrying 341,000 passengers a year. The North British Railway introduced through trains between Edinburgh and London in 1848 (though this still using temporary bridges over the Tweed at Berwick and the Tyne at Newcastle).

About Stage-coach History:

Stage-coaches were about the dissemination of information and ideas as well as the transport of people. Their importance is summed up by Dorian Gerhold:

Stage-coaches were the main form of fast transport in England and Wales for most of the century before railway…. They conveyed not only passengers but also information in various forms…. From 1784 most letters and London newspapers were conveyed by mail coach….. Letters might include market information, orders and invoices, banknotes and bills, as well as political information.

The more rapid conveyance of passengers and information contributed to the strengthening of the national market, the diffusion of London fashions, the breaking down of regional differences, and the potential for national political campaigns.

Before the Stage-coach

People were travelling by road in medieval times but generally this was by foot or on horseback. There were no scheduled public transport services.

The wealthy might occasionally travel by horse-drawn litter, but this was unlikely to be a comfortable or practical option for most journeys.

The old and infirm might travel in a long waggon which started to displace packhorses for carriage of goods over longer distances. Such waggons were drawn by horses in single file, and which travelled the full length of the journey (so speeds were similar to pack horses).

The concept of a four-wheeled closed carriage for people emerged in 14th century continental Europe in parallel with the introduction of suspension using transverse chains. “Chars branlants” (trembling chariots) were in use in France in the 1370s and were, for instance, recorded to have been used in 1405 when Queen Isabeau of Baviaria entered Paris. A superior and lighter design using longitudinal leather straps for suspension appeared in Hungary: it took its name from the village of Kotsee (or Cotzi), and this is said to be the origin of the word “coach”. Whilst they benefited from rudimentary suspension, these early coaches had no glass windows and the doors were closed by a bar, over which hung a leather strap.

In 1553, Queen Mary’s coronation coach was drawn by 6 horses from the Tower to the Palace of Westminster and was followed by 3 additional carriages. Other nobility did not want to miss out: the Earl of Rutland acquired one in 1555, Sir Thomas Hoby had one in 1566, and in 1579 the Earl of Arundel imported one of the new machines from Germany.

Such coaches did start to be used for longer distance travel but the need to rest and feed horses meant speed of travel was not significantly different from riding horseback – and unsophisticated coach design and poor roads limited their attraction.

The first more general public use of coaches came in the form of the hackney carriage within large towns in the early 17th century. (The name referred the type of horse used to pull them rather than a district of London.)

In his “Ten Years of Travel through Great Britain and other Parts of Europe” Fynes Moryson in 1617 reports that:

“Sixtie or seventy yeeres agoe, Coaches were very rare in England, but at this day pride is so far increased, as there be few Gentlemen of any account (I mean elder Brothers) who have not their Coaches, so as the streetes of London are almost stopped up with them…. For the most part Englishmen, especially in long journies, used to ride upon their owne horses. But if any will hire a horse, at London they used to pay two shillings the first day, and twelve, or perhaps eighteene pence a day, for as many dayes as they keepe him, till the horse be brought back home to the owner, and the passenger must either bring him backe, or pay for the sending of him, and find him meate both going and comming. In other parts of England a man may hire a horse for twelve pence the day…. Likewise Carriers let horses from Citie to Citie…. Lastly, these Carryers have long covered Waggons, in which they carry passengers from City to City: but this kind of journeying is so tedious, by reason they must take waggon very earely, and come very late to their Innes, as none but women and people of inferiour condition, or strangers (as Flemmings with their wives and servants) use to travell in this sort.”

London was growing fast (50,000 in 1500; 200,000 in 1600; 500,000 in 1700) and this is where the use of coaches first multiplied. Inevitably there was a backlash. This included a 1636 proclamation by Charles I:

“for the restraint of the multitude, and promiscuous use of coaches about London and Westminster”.

Use of coaches to travel to and from London also drew criticism and concern about the effect on behaviour – particularly of women. John Crossel wrote a pamphlet demanding the suppression of these conveyances:

“These coaches make gentlemen to come to London upon very small occasion, which otherwise they would not do but upon urgent necessity ; nay, the conveniency of the pas- sage makes their wives often come up, who rather than come such long journeys on horseback, would stay at home. Here, when they come to town, they must go in the mode, get fine clothes, go to plays and treats, and by these means get such a habit of idleness and love of pleasure, that they are uneasy ever after.”

Origins of the Stage-coach

The coach had arrived. The public were using hackney carriages in town. By 1610 there was an advertised service in Edinburgh between the city and its main port Leith, 3 miles away. The wealthy were starting to use their own (or hired) coaches and post-chaises to travel the country.

The provision of horses for hire was increasing. This was in part linked to the still rudimentary postal system. Postmasters (often innkeepers) were required to provide relays of horses on the four great post roads (from London to Dover, Plymouth, Holyhead and Scotland). Regulations restricting their use by riders carrying official letters were flaunted; it became accepted that they could also be hired to “others riding poste with horse and guide about their private business.”

The next step of longer distance public coach services was a natural one since private “posting” was expensive with perhaps 1 or 2 passengers accompanied by their own footmen to make arrangements for horses and accommodation.

There are references to coach services by the 1640s. For instance, Harper cites a journey by John Taylor in 1648 to the visit the captive Charles I on the Isle of Wight in 1648; they

“hired the Southampton Coach, which comes weekly to the Rose, near Holborn Bridge”.

The first regular stage-coach services were launched in the 1650s. They were radically different from what went before in that costs were shared by travelling with others and, with regular stops to change horses, faster speeds could be achieved.

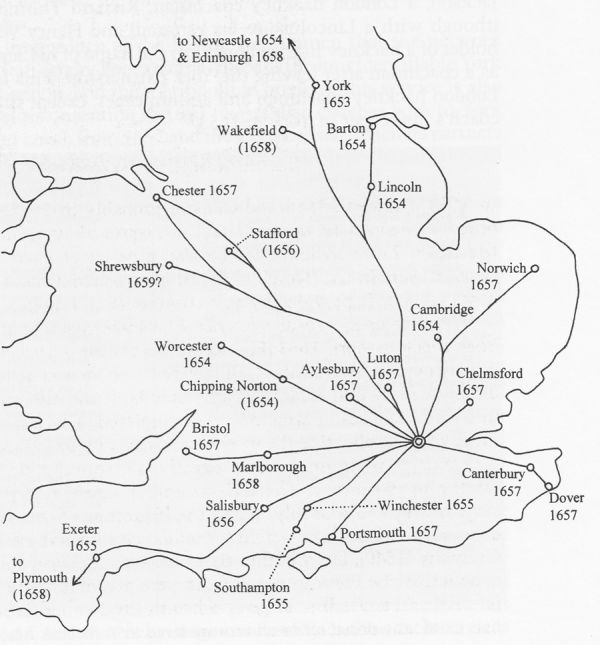

The London to York service was the earliest but, as shown by the map below, a national network radiating from London soon started to develop.

First references to stage-coach services. Gerhold, Map 11

The first York coach was described as taking 14 passengers “having 3 distinct rooms” (perhaps a development of the earlier “coach-waggon”). However, the norm soon became 6-seater coaches drawn by 2 or 4 horses (or maybe 6 in winter).

Prices varied but were typically over 2 pence per mile, so it was a means of transport for the well to do, rather than the masses. Stage-coaches became popular with the county gentry and professional people; early routes were often designed to connect London with the county towns.

Evolution of the Stage-coach Industry

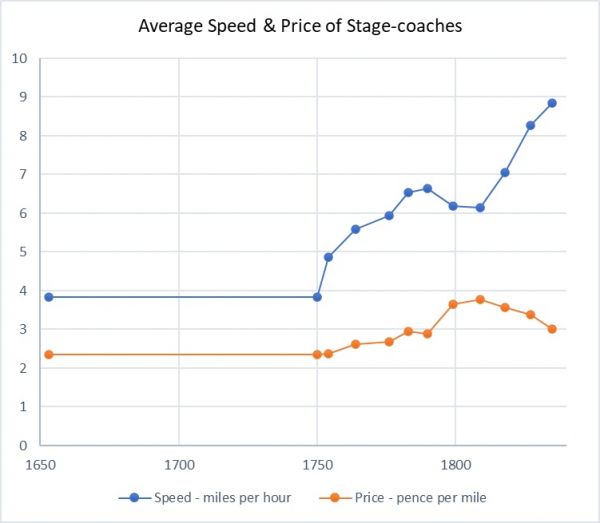

Historians have spent years of their time delving into the morass of records relating to stage-coach operation. Their very broad conclusions on speeds and pricing are:

- fairly stable speeds and prices between 1650 and 1750

- a rapid improvement in speeds due to better roads and coaches from the 1750s

- a lull in speeds at the end of the 18th century – perhaps reflecting the need to compensate for higher operating costs

- a final surge in speeds combined with falling prices in the early 19th century.

Based on data averages by Gerhold.

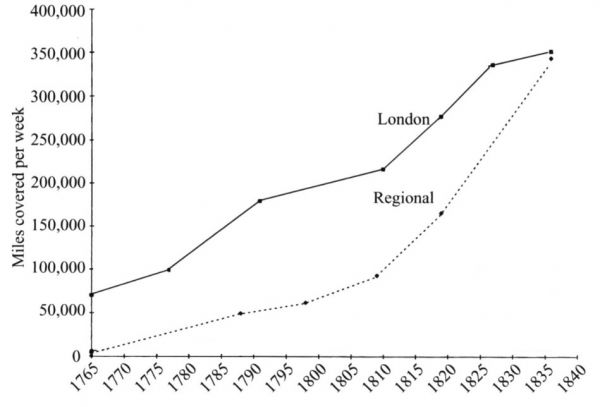

Growth in usage was quite modest for the first hundred years that stage-coaches operated. Total usage of stage-coaches grew only modestly for their first hundred years but then there were spurts during the 1770s and 1780s, and again in the 1810s and 1820s. The initial growth tended to focus on the radial routes from London, but there was catch-up as the interconnecting regional routes grew out from the expanding towns and cities.

The routes from London to major ports such as Holyhead, Liverpool, Bristol and Plymouth were increasingly important as Ireland and the colonial territories grew in economic significance. Unsurprisingly there is also evidence of growth between 1760 and 1810 driven by military activity associated with the Seven Years War, the War of American Independence, and the Napoleonic Wars.

The graph below estimates the total miles covered each week though this may understate total growth since coach occupancy was increasing (until 1750 most coaches could carry just 6 passengers, whilst by 1810 many could carry 12 to 18).

Source: Gerhold, The development of stage coaching, Fig 4

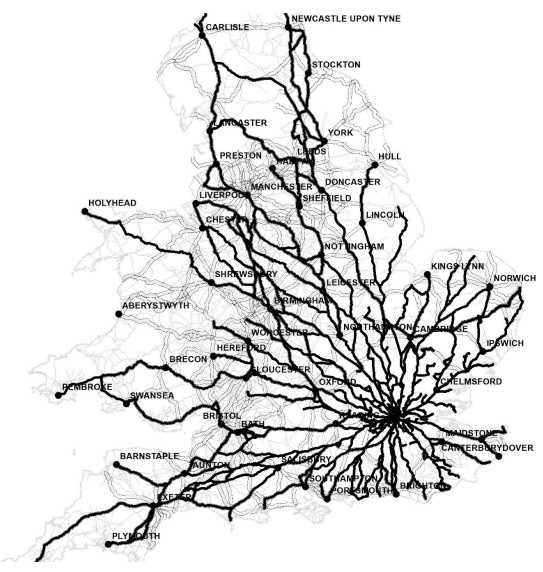

By the 1830s there were few towns across the country which were not connected to the stage-coach network:

Stage-coach network 1830. London routes in black, country routes double grey, turnpiked roads single grey lines.

Source: Rosevear, Bogart & Shaw-Taylor, The spatial patterns of coaching in England and Wales from 1681 to 1836

Stage-coach Design

The early coaches were heavy and basic in design. The carriage body was formed of a wooden frame covered with thick leather, low slung from leather braces fixed to front and rear “axletrees”. Curtains and wooden shutters took the place of windows and doors. The body of the coach was prone to swing from side to side, often inflicting travel sickness on its occupants.

There were several major innovations in coach design, the most noteworthy being glass windows and steel springs.

The first known private carriage with glass windows was that of the Duke of York in 1661, but stage-coaches with glazed windows (“glass-coaches”) did not start to appear until the early 18th century.

The introduction of steel springs was also in the early 18th century. The first application of elliptic leaf springs to coaches was by Obadiah Elliott who had obtained a patent in 1695.

Further improvements which ensured the general use of steel springs were made by Rotherham inventor, Richard Tredwell. In 1762 he received a patent for an improved leaf spring, and in the following year claimed a “new method of making and constructing springs for hanging of coaches” using helical (coil) steel springs.

Three-quarter-elliptic leaf spring on a Spanish carriage. Image Credit: Rios, Wikimedia, CC BY-SA 4.0

The new designs greatly reduced both the shocks inflicted on the vehicles by poor roads, and the discomfort of the passengers. They facilitated lighter construction and enabled higher hung coaches. The position of the coachman was much improved by positioning on a “lofty box”, benefiting from suspension, better placed for visibility and command of the horses.

A description of a coach of the late 18th century is provided by Harper, drawing on Walter Scott:

They were covered with dull black leather, thickly studded with broad-headed nails, tracing out the panels. The heavy window-frames were painted red, and the windows themselves provided with green stuff or leather curtains which could be drawn at will. On the panels of the body were displayed in large characters the names of the places whence the coach started and whither it went. The coachman and guard (when there was a guard at all) sat in front upon a high narrow boot, often garnished with a spreading hammer-cloth with a deep fringe. The roof rose in a high curve. The wheels were large, massive, ill formed, and generally painted red. In shape the body varied. Sometimes it resembled a distiller’s vat somewhat flattened, and hung equally balanced between the immense back and front springs; in other cases it took the form of a violoncello case, which was, past all comparison, the most fashionable form; again, it hung in a more genteel posture, inclining on the back springs, in that case giving those who sat within the appearance of a stiff Guy Fawkes. The foremost horse was still ridden by a postilion, a longlegged elf dressed in a long green and gold riding-coat and wearing a cocked hat; and the traces were so long that it was with no little difficulty the poor animals dragged their unwieldy burden along. It groaned, creaked, and lumbered at every fresh tug they gave it, as a ship, beating up through a heavy sea, strains all her timbers.

It was about this time that “boots” were added front and back to the roofs of coaches. This enabled more passengers to travel “outside” with less risk of falling.

Another notable stage-coach designer was John Besant. In the 1790s he introduced coaches with tighter turning circles and a feature to reduce the risk of wheels becoming detached whilst in motion. With his partner John Vidler, he enjoyed a monopoly on the supply of stage-coaches for the Royal Mail in the early 19th century.

Stage-coach Growth and the Turnpikes

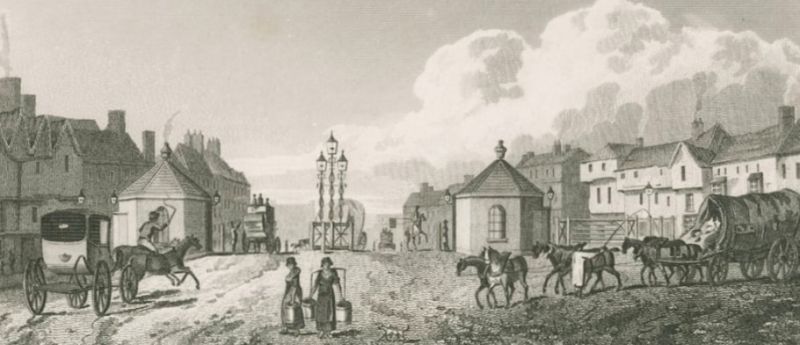

Kennington Turnpike c1790, Paul Sandby, Lambeth Archives

There was dramatic growth in both turnpikes and stage-coaches in the late 18th century. To what extent one caused the other has been much debated though it is largely immaterial. Undoubtedly, it was a symbiotic relationship – and there were other factors at play which influenced both.

There was relatively little increase in stage-coach traffic in the early days of the turnpikes, perhaps reflecting the fact that until they started to form a joined-up system, and the real investment in road surfaces, gradients and bridges came about, they were not likely to dramatically change journey times.

By the 1770s and 1780s when we do see more rapid stage-coach growth, this was also very much associated with significant technical improvements in coach design, increasing urbanisation and industrialisation.

Military needs and goods transport were other important drivers for the development of the turnpikes. In the 1730s General Wade had constructed some 250 miles of road in Scotland but the rebellion in 1745 led the Government to pay special attention to the subject of road-improvement between England and Scotland. Across the country there were increasing flows of commercial goods, and the carriers were for ever battling against inadequate roads. The system of parish responsibility and “statute labour” was discredited and a new model where the users paid was the only way to fund the needed investment.

Mail Coaches

A restored 18th century mail coach. Image credit: London Postal Museum

Until 1784 the Royal Mail had been carried by relay on horseback but at the instigation of Palmer the use of mail-coaches operated under franchise was trialled.

Under the old system, the journey from Bristol to London had taken up to 38 hours. Palmer’s stagecoach left Bristol at 4pm on 2 August 1784 and arrived just 16 hours later. William Pitt, Chancellor of the Exchequer, authorised additional routes and by 1797 there were 42 destinations served.

Mail-coaches were given priority on the road, they did not pay tolls, and they were allowed to carry a few passengers to mitigate costs. With speed of the essence, journey times were reduced. They soon became the elite way to travel.

The mail coaches were distinctive not only in terms of their livery. They all had both a coachman and a guard to ensure security. As the mail coach approached a turnpike the guard would sound his horn to alert the toll-keeper, so he could have the gate standing open.

The “Mails” travelled through the night so were equipped with up to 5 bright lamps to illuminate the road and help counter potential attacks.

The guards were in charge and were armed with a blunderbuss and a pair of pistols; they were only paid 10 shillings per week by the government but received much more in tips, often from bankers who entrusted money and valuables in their care.

In 1787 a standardised mail coach design was adopted by The Post Office. The “patent coaches” were designed by John Besant who later, in partnership with John Vidler of Millbank, enjoyed the monopoly of their supply. The coaches were taken to their works to be cleaned and oiled before return to the various coaching inns for their evening departures.

It was of course the mail contractors who had to pay for the coaches and their maintenance so inevitably there were regular complaints about their design and condition. Passengers, too, were not always impressed: engineer, Mathew Boulton, complained about the coach in which he travelled to Exeter in 1798:

“I had the most disagreeable journey I ever experienced the night after I left you, owing to the new improved patent coach, a vehicle loaded with iron trappings and the greatest complication of unmechanical contrivances jumbled together, that I have ever witnessed. The coach swings sideways, with a sickly sway, without any vertical spring; the point of suspense bearing upon an arch called a spring, though it is nothing of the sort. The severity of the jolting occasioned me such disorder that I was obliged to stop at Axminster and go to bed very ill. However, I was able to proceed next day in a post-chaise. The landlady in the ‘London Inn’ at Exeter assured me that the passengers who arrived every night were in general so ill that they were obliged to go supperless to bed; and unless they go back to the old-fashioned coach, hung a little lower, the mail-coaches will lose all their custom.”

The number of passengers allowed on the “Mails” was controlled by law. There were 4 inside and, by the 1820s, up to 3 “outside” (1 on the box seat and 2 on the roof behind). No one was permitted to sit at the back near the guard or the mail box.

Mail coaches continued to run between some provincial towns until the 1850s but the last regular service from London was to Norwich and this was culled in 1846.

Stage-coach Operators & Infrastructure

The early coach masters tended to be London based with backgrounds as hackney coachmen, or sometimes innkeepers, coach makers or carriers. Two of those running the Chester coach from 1657 (William Dunston and Henry Earl) had been overseers of the Fellowship of Hackney Coachmen; the third (William Fowler) was a coach maker.

By the late 17th century there more regionally based operators reflecting the spread of the coaching network. There was also more involvement by the goods carriers who traditionally were based outside of London. In 1690, 19 of the 55 longer distance services from London recorded by Delaune were operated by carriers.

The central role of horses, catering and accommodation along the stage-coach routes resulted in the development of numerous coaching inns, many of which we still see today. There were many repeating features: the narrow-arched entrance; the central courtyard; the multi-storey galleried rooms; and prominent, distinctive signage. These inns became focal points within both the growing cities and many smaller towns.

Inner yard of the Spread Eagle Inn on Gracechurch Street, Shepherd, c1850. Image credit: British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

In the cities, coaching inns were communications hubs, part of an integrated travel network, linking national and local services. In addition to overnight accommodation, the larger inns provided booking facilities where it became possible to configure through-journeys to anywhere in the country, and even to the main continental European destinations. A journey may have needed several changes of stage-coach and overnight stops but, for a price, it could be arranged by the booking-clerk.

The inn-keepers were often involved as partners in coach operating businesses: the Lincoln coach in the early 1730s was run by John Vinter (innkeeper at the Dolphin, Huntingdon), and Thomas Yonick, a London coachman. Inns serving the mail coaches were able to double as post offices until these were separately established.

Operating successful stagecoach services required entrepreneurial and practical flair. Operators needed to know their customer base and build trust. They needed to own, or establish reliable partners with, inns and stables the length of their routes. They needed to manage widely dispersed staff. The successful ones established significant companies, which outlived the stagecoach era.

One example of the great coach masters of the early 19th century will provide a flavour of the characters involved and the scale of their businesses.

William James Chaplin

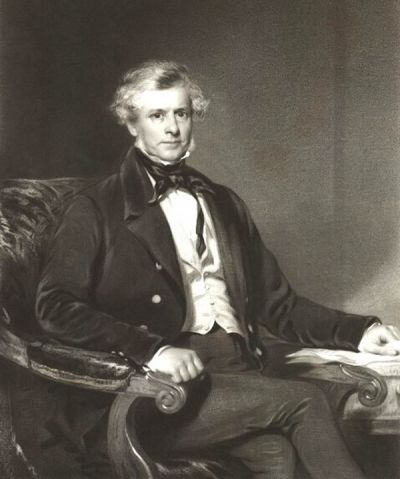

William Chaplin was a coachman with a small-scale operation at Rochester serving the Dover Road. This was likely to have been a lucrative route at the end of the 18th century with military activity in Europe. He started to take on services on other major roads from London in the 1790s and it was his son, William James Chaplin, born in 1787, who went on to build the largest single coaching business.

In about 1825 Chaplin took over the business previously run by William Waterhouse at the Swan with Two Necks in Gresham Street. The yard was cramped so to allow expansion he created underground stables for 200 horses. He also acquired the White Horse in Fetter Lane, and the Spread Eagle and Cross Keys in Gracechurch Street. Chaplin owned large stables at Purley on the Brighton Road, at Hounslow on the Western roads, and at Whetstone on the Great North Road.

William James Chaplin by Henry Thomas Ryall, after Frederick Newenham, 1850

Image credit: National Portrait Gallery, NPG D32858

In 1838 Chaplin’s coaching business reached its peak. He had a fleet of 68 coaches and 1,800 horses. He employed 2,000 people. He was said to have supplied horses for the first stages of 14 of the 27 coaches leaving London each night. Amongst his famous coaches were the Manchester “Defiance”, the Birmingham “Greyhound”, and the “Stamford Regent”.

He used the emblem of the Swan with Two Necks, and those of his other inns, on the sides of his red and black coaches.

He was renowned for his business acumen and intimate knowledge of all aspects of the business; he was given the somewhat disrespectful nickname of “Billy Bite’em Sly.”

Despite his coaching background, Chaplin went on to embrace the arrival of the railways. In conjunction with rival coach master, Benjamin Horne, he worked closely with the new London and Birmingham Railway company, and (with Pickfords) shared in the monopoly for parcels on this line. In the 1850s he redeveloped the site of the Swan as a large warehouse for his growing parcels business. He later became chairman of the London and South Western Railway, a director of railway companies in France, and an MP.

Demise of the Stage-coach

It was the railways which rapidly snuffed out the stage-coach in the 1840s, but the threat of steam had been evident earlier. In 1827 Goldsworthy Gurney had patented and demonstrated a steam engine which could pull a steam carriage on the road; by 1831 the steam engine was incorporated into the coach and a service was operating between Cheltenham and Gloucester.

There was much public opposition, not least from the turnpike companies who escalated tolls dramatically for these heavy vehicles. There were many practical challenges and the steam pioneers instead concentrated on rails rather than roads.

Gurney Coach. Image credit: Harper, after G Morton

It was an awkward time for the coaching companies. Numbers wishing to travel were increasing and coach services expanded – but the threat of rail was imminent. There was intense competition and fares tumbled.

In 1830, the Liverpool and Manchester Railway launched the world’s first regular steam hauled passenger service. We marvel today at the speed of adoption of new technologies but within 15 years a national network of railways had appeared. As disruptive technologies go, this was one of the most dramatic. The economics of long-distance travel were transformed; speeds rose dramatically while prices came down.

The coach operators played on the safety issues to deter their adoption; a little ironic since, as with air travel today, a rail accident may be more deadly but there were frequent accidents involving coaches.

Road versus Rail, Cooper-Henderson, c1843

A smart stage-coach racing safely along the road, while a dramatic railway accident attracts the smug attention of the passengers.

At the close of 1838 a newspaper said:

“A few months ago no fewer than twenty-two coaches left Birmingham daily for London. Since the opening of the railway that number has been reduced to four, and it is expected that these will be discontinued, although the fares by coach are only 20s inside and 10s outside, whilst the fares for corresponding places on the railroad are 30s. and 20s.”

The last long distance London coach service was deemed by Harper to be that to Bedford, withdrawn in 1848 following opening of the Bletchley and Bedford branch railway.

Coaches serving local towns continued – often providing linkage with the new rail services.

Stage-coach History Miscellanea

The Flying Coach

The description “Flying Coach” was attached to many of the faster stage-coach services. As early as 1667 there was reference to the Bath Flying Machine.

“All those desirous to pass from London to Bath, or any other Place on their Road, let them repair to the ‘Bell Savage’ on Ludgate Hill in London, and the ‘White Lion’ at Bath, at both which places they may be received in a Stage Coach every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday,69 which performs the Whole Journey in Three Days (if God permit), and sets forth at five o’clock in the morning.

Passengers to pay One Pound five Shillings each, who are allowed to carry fourteen Pounds Weight—for all above to pay three-halfpence per Pound.”

The phrase does not indicate a special design of coach and, at least in the 17th century, did not necessarily imply a faster running speed. It was much more to do with extended hours of operation – sometimes into the night.

In 1754, the Manchester “Flying Coach” was introduced, travelling from Manchester to London in just four and a half days. A similar service began from Liverpool 4 years later, using coaches with the new steel spring suspension; these coaches reached 8 miles per hour and completed the journey in just 3 days.

These new faster coaches often operated with shorter stages and more regular replacement of horses.

The Highwaymen

Dick Turpin’s Ride to York Image Credit: Ronald Simmons

Stage-coaches and their passengers were prone to robbery – but whether more so than those travelling by other means is hard to say. One of the earlier records of a theft comes from the London Gazette in 1684:

“A GENTLEMAN (passing with others in the Northampton Stage Coach on Wednesday the 14th instant, by Harding Common about two miles from Market-street) was set upon by four Theeves, plain in habit but well-horsed, and there (amongst other things) robbed of a Watch; the description of it thus, The Maker’s Name was engraven on the Back plate in French, Gulimus Petit à Londres; it was of a large round Figure, flat, Gold Enamelled without, with variety of Flowers of different colours, and within a Landskip, and by a fall the Enamel was a little cracked; It had also a black Seale-Skin plain Case lined with Green Velvet. If any will produce it, and give notice to Mr. Samuel Gibs, Sadler near the George Inn Northampton, or to Mr. Cross in Wood Street, London, he shall have a Guinea reward.”

Many of the stories about highwaymen were undoubtedly exaggerated – not least for the benefit of the coachmen and guards who might collect more generous tips from their clients.

Later robberies take on the form of organised heists which are more familiar to us today. In 1822 the Ipswich Mail was targeted and notes worth £31,198 disappeared (though £28,000 was recovered). In June 1826, seven bags were taken from the Dover Mail between Chatham and Rainham, and in the following year the Warwick Mail being robbed of £20,000.

Hidden Costs

We rage today against the hidden costs of low-cost airlines, but stage-coach customers needed to budget for their trips with “eyes wide open”. The headline price of between 2 pence to 3 pence per mile was just the starting point.

Just as today, there were limits on how much luggage you could take, with a scale of charges applicable.

More fundamental of course was the need to factor in the cost of meals, refreshments and accommodation. In the early days, coach timings were unreliable and daily distances covered might only be 30-50 miles, so it would have been hard to accurately define total expenses in advance.

Then there was tipping. To ensure they were well looked after, travellers needed to tip not only the coachman but also the guard (if applicable) and staff at the inns.

Hobson’s Choice

Image credit: Cambridge City Council

Thomas Hobson took on the family’s carrying trade when his father died in 1568. It operated between the Bull in Bishopsgate Street (London) and The George Inn in Cambridge where Hobson’s stable was situated was located on the current grounds of St Catharine’s College. His business grew and as well as operating a regular waggon between the cities, he was the appointed carrier of the post for the university, and he hired out saddle-horses.

Hobson soon realised that his fastest horses were the most popular, and thus overworked. To overcome this situation he established a strict rotation system, allowing customers to rent only the next horse in line. His “take it or leave it” policy has come to be known as “Hobson’s choice”.

The success of Hobson’s business allowed him to buy Anglesey Priory in 1625 which he converted into a country house for one of his daughters.

Red Tape

Stage-coaches were the focus of much legislation though attempts at top-down control often met with limited success.

Amongst the detailed provisions of Acts in 1788,1790 and 1806:

Coachmen were forbidden to let others drive, under a penalty of from 40s to £5 (later raised to £10).

Stage-coaches were not to carry more than 6 passengers on the roof or more than 2 on the box in addition to the coachman. For every passenger in excess the coachman was liable to a penalty of 40s, and if he was proprietor, or part proprietor, this penalty was raised to £4 (later made more restrictive).

Setting down a passenger near a turnpike gate, and taking him up on the other side, with intent to evade the outside passenger regulation (enforced by the toll-keeper) could be punished by imprisonment of 14 days to a month.

From March 1st, 1811, it became unlawful for any driver, owner or proprietor to permit luggage, or indeed any person, on the roof of a coach the top of which was more than 8 ft 9 in from the ground, or whose gauge was less than 4 ft 6 in. The penalty for infringement was £5.

Luggage on ordinary stage-coaches was not to exceed 2 ft in height, or on three-horsed coaches, 18 in, with a penalty of £5 for every inch in excess. Luggage might be carried to a greater height if it was not, in all, more than 10 ft 9 in from the ground.

Intoxicated coachmen came in for a maximum £10 penalty, or the alternative of a term of 3 to 6 months’ imprisonment.

Rural Rides

William Cobbett in his 1830 study of the English countryside, Rural Rides, captured the romance of the stage-coach felt by many:

The finest sight in England is a stage coach ready to start. A great sheep or cattle fair is a beautiful sight; but in the stage coach you see more of what man is capable of performing. The vehicle itself, the harness, all so complete and so neatly arranged; so strong and clean and good. The beautiful horses, impatient to be off. The inside full and the outside covered, in every part with men, women, children, boxes, bags, bundles. The coachman taking his reins in hand and his whip in the other, gives a signal with his foot, and away go, at the rate of seven miles an hour.

One of these coaches coming in, after a long journey is a sight not less interesting. The horses are now all sweat and foam, the reek from their bodies ascending like a cloud. The whole equipage is covered perhaps with dust and dirt. But still, on it comes as steady as the hands on a clock.

May Day at Sutton

Johann Peter Neeff (1753-1796)

Traditions and folklore grew up around the stage-coaches. Harper recounts nostalgically:

May Day was then the great merrymaking festival, but the first coach that ventured along the roads, now beginning to set after the winter’s rains, had a welcome of its own. At Sutton-on-Trent, on the Great North Road, the springtide custom of welcoming the early coaches was royally observed, and kept up for many years. No coach, during a whole week of jollity, was suffered to proceed through that jovial village without it halted and ate and drank as only Englishmen could then drink and eat. Guards, coachmen and passengers were freely feasted, willy-nilly. Young and old plied them with the good things, spread out upon a tray covered with a beautiful damask napkin, and heaped with plum-cakes, tartlets, gingerbread, and exquisite home-made bread and biscuits; while ale, currant and gooseberry wines, cherry brandy, and occasionally spirits, were eagerly pressed upon the strangers.

Stage-coach History – More Information

Stage-Coach and Mail in Days of Yore, Harper, 1903 – Vol1, Vol2

Pratt, A History of Inland Transport and Communication in England, 1912

Boyer, Mediaeval Suspended Carriages, Speculum, July 1959

Gerhold, Carriers & Coachmasters, Phillimore, 2005

Gerhold, The development of stage coaching and the impact of turnpike roads, Economic History Review, 67-3 (2014)

Rosevear, Bogart & Shaw-Taylor, The spatial patterns of coaching in England and Wales from 1681 to 1836, 2019

Top of page image: J. & W. Chaplin’s Dover–London Stage, John Cordrey, 1814. Credit: Yale Center for British Art

Schnebbelei’s “Entrance to London from Islington” (1810). A reminder that the roads were not the sole preserve of the stage-coach. In the distance, spot the stage-coach and horse-back rider; in the foreground, a post-chaise and a waggon.