London Coaching Inns and the Great North Road

The coach itself is just one element of your journey. Trips may take several days; your horses need to be regularly changed; schedules are easily disrupted: so arrangements for meals and board are a key component.

There were dozens of coaching inns the length of the Great North Road but those in London were the largest and best known. As travellers to and from the east of Britain have since passed through King’s Cross, so travellers in the 17th and early 18th century would have been very familiar with the inns which specialised in services to the north and east.

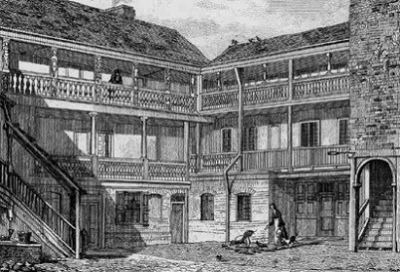

The London coaching inns developed a familiar style with multi-storey galleried guest rooms. Whilst some of the old inns around the country live on, this is not the case in London where intensive re-development means most do not survive in any form. We will concentrate our attention of a handful which achieved prominence and which were directly involved in serving passengers travelling the Great North Road.

About London Coaching Inns

By the early 19th century there were 120 London coaching inns within a city which was far more compact than today. It is difficult to appreciate how high profile they were at the time. With no cars, buses, trains or planes, so horses or horse-drawn coaches were the only option for travel. And people were travelling; to towns and cities across the country and indeed to continental Europe. Many of the stage-coach services were aligned with specific London inns. The network of inns had shades of today’s airport or railway hotels: perhaps with a pinch of Victoria coach station, motorway services and a Travel Lodge thrown in. Hustle, bustle, celebrity, glamour, grime and crime. Large numbers of people rushing to get somewhere – or helping others to do so.

The Angel, Islington

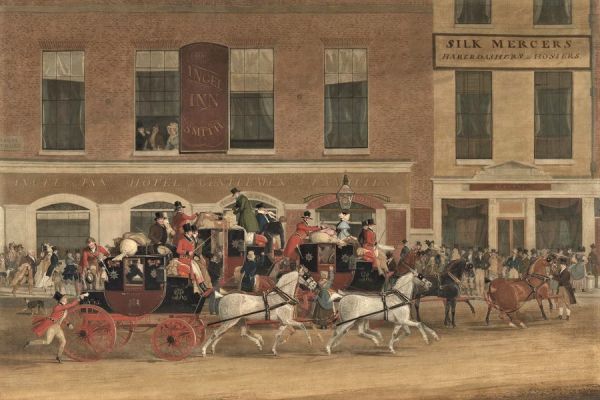

The Royal Mail Coaches for the North Leaving the Angel, Islington James Pollard,1827

The Angel was the largest of a row of coaching inns along Islington High Street. Located at the edge of London directly on the Great North Road it was a prominent landmark before, during and after the coaching period. Lying outside the City of London it was perhaps the first pick-up rather than the point of departure.

There was an inn on the site during the 16th century and by 1614 it was called the Angel. By this time it was being used for the holding of manorial courts. It was rebuilt in about 1638 and it is likely that this version of the Angel was one of the galleried courtyard ranges that survived into the early 19th century. It is thought that the three storey front block with 12 bays was rebuilt in brick sometime later in the century.

William Hogarth’s 1747 engraving of The Stage Coach is believed to represent the Angel, Islington

The building of the New Road in 1756 bisected the Angel Inn site. The galleried inn was on the northern side, while the stables were cut off on the southern side. The New Road was London’s first ring road: originally conceived as a 40 foot wide drove road (with tolls) around the capital’s northern boundary it is now better known as Euston Road and Pentonville Road. The Angel benefited from the extra traffic and in addition to accommodation provided assembly rooms for public meetings.

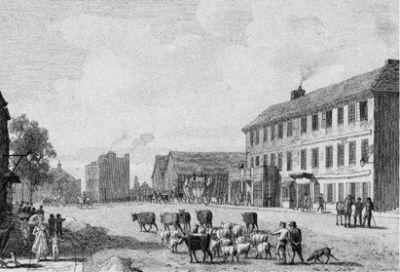

The Angel Inn in 1818 – Front looking south along Islington High Street, and courtyard to rear

By the start of the 19th century, fields south of the Angel were being built on. Surplus land was sold for development and the inn rebuilt in 1820 on a reduced scale as ‘The Angel Inn Tavern and Hotel for Gentlemen and Families’.

The Angel Inn from the south-east in about 1828 (also showing Nos 3–17 Islington High Street)

Urbanisation was rapid over the next decade. In Oliver Twist, the first monthly instalment of which appeared in February 1837, Dickens describes Noah Claypole and Charlotte trudging into London by the Great North Road; arriving at The Angel at Islington,

‘Noah wisely judged, from the crowd of passengers and number of coaches, that London began in earnest’.

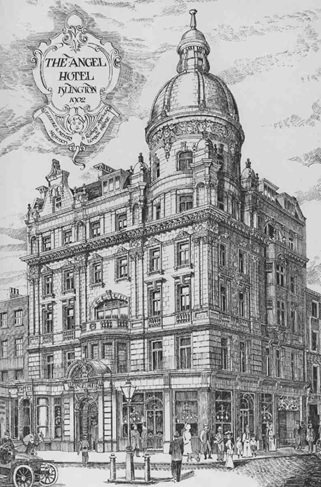

The coaching trade fell away as the railways developed. The stables were sold in 1883 to be adapted for the horses of the London Street Tramways Company. In 1901 the inn shared its name with the new tube station on the Northern Line. The Angel was rebuilt in 1903 as the Angel Hotel, and in the 1920s housed a prominent Lyons’ Café. Since then uses have included shops, offices, and a bank. There is still a Weatherpoons pub!

The Angel from the south-east in the late 1890s

Plans for the 1903 building – including a motor car entering the scene

The Bull and Mouth

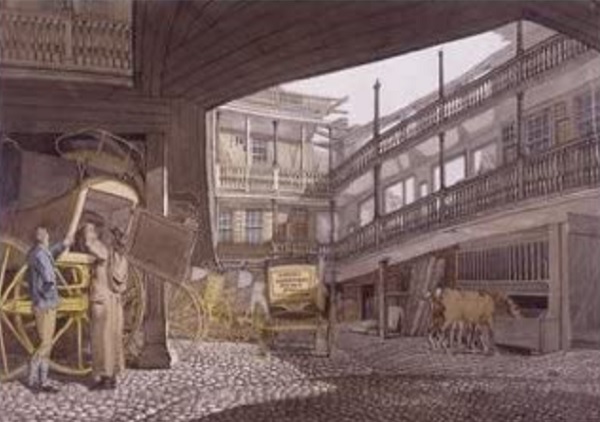

Yard of The Bull and Mouth c1820. Thomas Hosmer Shepherd, engraved by W Watkins

The original Bull and Mouth predates the Great Fire of London and gave its name to a street of the same name. It was rebuilt and is first recorded on John Ogilby and William’s Morgan’s 1676 Map of the City. The origin of the name is often said to relate to the siege of Boulogne and its harbour in the mid 1540s though others, more convincingly, link it to the inscription displayed on the old hotel:

“Milo the Cretonian

An ox slew with his fist,

And ate it up at one meal,

Ye gods, what a glorious twist!”

This unusual sculpture was the sign of the Bull and Mouth inn. It features Milo, a Greek wrestler, sometimes depicted carrying a bull upon his shoulders

The inn was an important arrival and departure point for coaches from all over England but particularly from the north and Scotland, being conveniently located close to the start point of the Great North Road. The General Post Office at St Martin’s Le Grand, built 1829, was located close by.

In 1823 the Bull and Mouth was acquired by coaching entrepreneur Edward Sherman. He rebuilt the inn in 1831 as the Queen’s Hotel though the old name remained in use for many years. In its new guise the site provided underground stabling for 700 horses.

According to Harper:

The money for these enterprises came from three old and wealthy ladies whom he married in succession. If the stranger, unversed in the build and colour of coaches, could not pick out the somewhat old-fashioned, bright-yellow vehicles as Sherman’s, he was helped in identifying them by the pictorial sign of the inn painted on the panels—’ rather a startling one, by the way, to the rustics.

In its prime the ” Bull and Mouth ” sent forth the Edinburgh and Aberdeen Royal Mail by York; the Edinburgh, Glasgow, and Aberdeen coach by Ferrybridge to Newcastle, where the Glasgow passengers changed; the Glasgow and Carlisle Royal Mail ; the Newcastle ” Wellington ” ; Shrewsbury and Holyhead ” Union ” and ” Oxonian ” ; Birmingham ” Old Post Coach ” and ” Aurora ” ; Leeds Royal Mail and ” Express ” ; and Leicester ” Union Post Coach.”

There’s even a reference in Dickens’ Haunted Man:

It was a peculiarity of this baby to be always cutting teeth. Whether they never came, or whether they came and went away again, is not in evidence; but it had certainly cut enough, on the showing of Mrs. Tetterby, to make a handsome dental provision for the sign of the Bull and Mouth.

The Queen’s Hotel met its demise when the site was required for an extension of the General Post Office in 1887. This also included “Bull and Mouth Street which had included the entrance to the coaching stables. The famous old coaching-stables were in their final years used as a railway receiving office for goods, under the name of Sherman’s old competitor, Chaplin.

A representation of the Bull and Mouth which had decorated the front of the Queen’s hotel was removed to the rotunda garden of the Museum of London

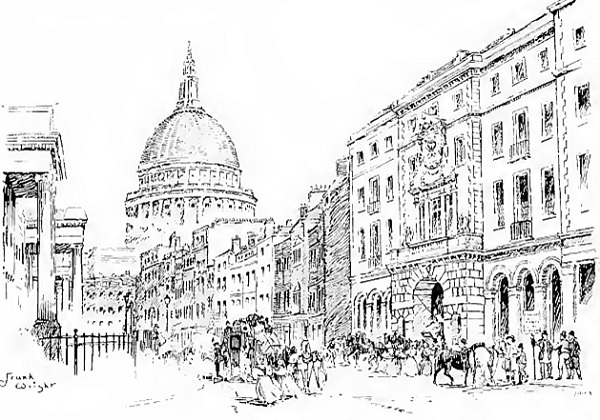

St. Martin’s-le-Grand , with General Post Office on the left and Bull and Mouth (afterwards the Queens Hotel) on the right

The George and Blue Boar

The courtyard of the Old Blue Boar tavern in Holborn, London, England, – from an old engraving c. 1700

The George and Blue Boar, Holborn was a medieval inn with some interesting historic connections. Prisoners on their way to the gallows at Tyburn would stop here for a last drink.

After a tip-off in 1647 Cromwell, with son-in-law Ireton, visited the George and Blue Boar dressed as troopers. They supped beer whilst waiting for the arrival of a messenger who was carrying a letter from the King to his wife. The letter made clear that Charles I had no intention of reaching any accommodation with the generals. His fate was set.

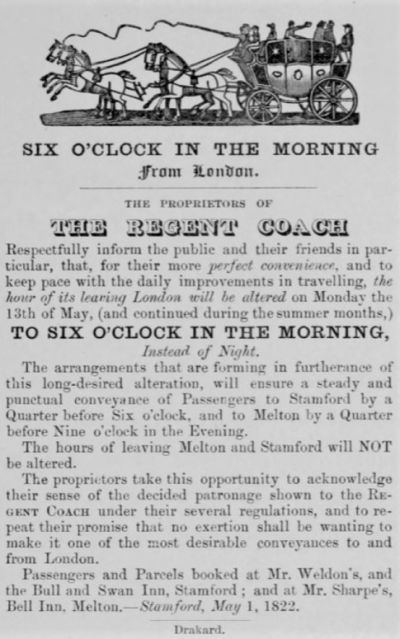

As a London coaching inn it was the point of departure for the Stamford Regent. The journey to Stamford took about 12 hours. The notice below announces plans to reschedule from an over-night to a day-time service in 1822.

Charles Birch-Reynardson reminisces in 1875 about an early morning departure from the George and Blue Boar:

Piles of luggage are being placed on the top and into the fore and hind boot of the coach. Where the luggage for ‘ four in and twelve out ‘ used to go I will leave you to make out, for I never could. But go it did ; and, having stowed our load away, we go out of the yard, down Holborn Hill, to the left up Cow Lane, through Smithfield, and make the best of our way to the ‘Peacock‘ at Islington, meeting droves of bullocks, sheep, and all sorts of conveyances coming from Smithfield. But we have arrived safely, neither upsetting anyone nor being upset ourselves. At this I often wondered, for the steam from the horses, the breath from the horses, the cattle, and the sheep, added to the dimness of the lamps and the dense fog, turned everything into worse than darkness. You might as well have looked inside a stewpan for any- thing that could be seen. ‘ Darkness in fact was visible.’ Everything else was invisible through the darkness of early morn and the fog.

Having achieved the ‘Peacock’ at Islington, a sight only to be seen there, and in those days, awaits us. A noise, I will call it a ‘sonus quadrupedans,’ assails your ears, as coach after coach comes up. All coaches going- anywhere north called there; and, as they came up the old hostler, or a man whoever he was, with a horn lantern, called out their names as they arrived on the scene. Up they come through the fog, but our old friend knows them all. Now ‘York Highflier,’ now ‘Leeds Union,’ now ‘York Express,’ now ‘Rocking- ham,’ now ‘ Stamford Regent,’ now ‘ Truth and Day- light,’ and others which I forget, all with their lamps lit, and all smoking and steaming, so that you could hardly see the horses. Off they go. One by one as they get their vacant places filled up, the guard on one playing ‘ Off she goes ! ‘ on another, ‘ Oh, dear, what can the matter be; ‘ on another, ‘ When from great Londonderry ; ‘ on another, ‘ The flaxen-headed ploughboy ; ‘ in fact, all playing different tunes almost at the same time.

The Science Museum holds a parcel receipt for a delivery to Robert Stephenson, suggesting he was staying at the inn in March 1853. Perhaps he was planning yet more railways to ensure the final demise of the coaching business, though by this stage of his illustrious career his attentions often focused on Europe and North America.

The old inn was demolished in the later in the 19th century making way for the Inns of Court Hotel.

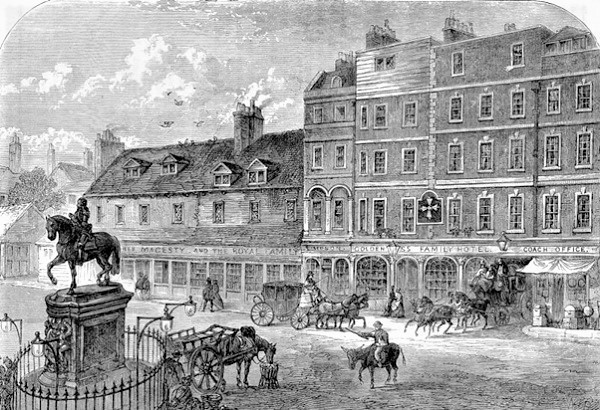

The Golden Cross

The Golden Cross is first recorded in 1643 when it stood in the former village of Charing, between the City and Westminster. It was named after the Eleanor’s Cross which originally stood near this site. The old cross was demolished in 1647 and the statue of King Charles erected in 1675.

In the 18th and 19th centuries departures included Dover, Brighton, Bath, Bristol, Cambridge, Holyhead and York.

The hazards of the low archway are highlighted in a scene in The Pickwick Papers. Dicken’s tale is said to have been inspired a true incident:

“Heads, heads – take care of your heads”, cried the loquacious stranger as they came out under the low archway which in those days formed the entrance to the coachyard. “Terrible place – dangerous work – other day – five children – mother – tall lady, eating sandwiches – forgot the arch – crash – knock – children look round – mother’s head off – sandwich in her hand – no mouth to put it in – head of family off.”

The inn was an early casualty of 19th century urban renewal. In 1827 the Golden Cross and its extensive stables were acquired for £30,000 by commissioners acting on behalf of architect John Nash. The result was a clean canvas for the creation of Trafalgar Square.

The Golden Cross with additional features c1820

Visitors to the Golden Cross Inn would have been well positioned to enjoy the entertainment of the nearby pillory. [Scene from 1809]

The Saracen’s Head, Snow Hill (Holborn)

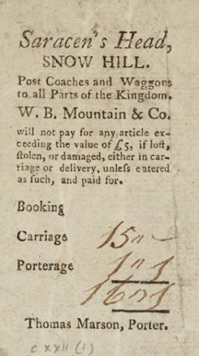

The Saracen’s Head coaching inn was close to the notorious Newgate prison and the church of St Sepulchre-without-Newgate. By the early 19th century it serviced 21 coaching services to many parts of the country but was particularly well known for destinations in the east such as Hertfordshire, Essex, Huntingdonshire and Lincolnshire.

The building dated back to at least the 16th century. In an account from 1522, the ‘Sersyns Head’ was used in the preparations for a visit by Emperor Charles V. The inn was recorded then as having 30 beds and stalls for four horses.

There is a reference in the diary of Samuel Pepys who visited on Monday 11 November 1661 when he shared a barrel of oysters with two colleagues.

The Saracens Head became part of the coaching business of Sarah Ann Mountain. Born in about 1770 she married inn keeper Butler William Mountain. She is said to have been both a beauty and effective business woman. Sarah built up a feed and grain business while also going into the stagecoach business, winning the right to run the Louth Mail. Not only did she operate inns and coach services but she also was involved in vehicle building.

We know that the inn was visited by painter, Joseph Mallard William Turner, in about 1814. A bill was found amongst his possessions.

The image above shows the inn during its demolition in 1868 with the tower of St. Sepulchre’s Church behind (woodcut, London Metropolitan Archives).

Dickens featured the Saracen’s Head in his novel, Nicholas Nickleby. Having described the filth, noise and executions of Snow Hill he goes on:

Near to the jail, and by consequence near to Smithfield also, and the Compter, and the bustle and noise of the city; and just on that particular part of Snow Hill where omnibus horses going eastward seriously think of falling down on purpose, and where horses in hackney cabriolets going westward not unfrequently fall by accident, is the coach-yard of the Saracen’s Head Inn; its portal guarded by two Saracens’ heads and shoulders, which it was once the pride and glory of the choice spirits of this metropolis to pull down at night, but which have for some time remained in undisturbed tranquillity; possibly because this species of humour is now confined to St James’s parish, where door knockers are preferred as being more portable, and bell-wires esteemed as convenient toothpicks. Whether this be the reason or not, there they are, frowning upon you from each side of the gateway. The inn itself garnished with another Saracen’s Head, frowns upon you from the top of the yard; while from the door of the hind boot of all the red coaches that are standing therein, there glares a small Saracen’s Head, with a twin expression to the large Saracens’ Heads below, so that the general appearance of the pile is decidedly of the Saracenic order.

When you walk up this yard, you will see the booking-office on your left, and the tower of St Sepulchre’s church, darting abruptly up into the sky, on your right, and a gallery of bedrooms on both sides. Just before you, you will observe a long window with the words ‘coffee-room’ legibly painted above it; and looking out of that window, you would have seen in addition, if you had gone at the right time, Mr. Wackford Squeers with his hands in his pockets.

Illustration from the original serialisation depicting sadistic schoolmaster, Squeers, feeding a terrified pupil on a seat inside the Saracen’s Head

After the death of her husband in 1833 Sarah Mountain retired to near Barnet and her son ran the inn. The inn was demolished in 1868 to allow construction of the Holborn Viaduct. Only a blue plaque remains.

The Spread Eagle

This London coaching inn was present by 1637 on Gracechurch Street, which follows the line north from the Roman crossing of the Thames.

It developed as a significant transport hub. In the 1760s there were 4 services per day to Camberwell, used in particular by counting-house (banking) employees. It was being used in the early 19th century by tea merchant, Thomas Twining. Great North Road coach destinations included Stilton, Peterborough and Lincoln.

By 1822 the Spread Eagle had been acquired by coaching entrepreneur William Chaplin who also operated from the Swan with Two Necks. It was in the style of other coaching inns being described as having ‘quaint galleries and stable-yard reaching down to Leadenhall Market’.

Print of ‘The Spread Eagle, Gracechurch Street, London, 1814. Artist: Robert Blemmell Schnebbelie

Chaplin had vied with Sherman during the boom years of the coaching era, building up networks of inns, stables and coach and wagon services. He is said to have had 1,800 horses, providing the animals for 14 of the 27 coaches leaving London each night. Chaplin was forward looking and had no hesitation in embracing the inevitable rise of the railways, providing local passenger and freight connections. He in fact became chairman of the London & South-West Railway. Along with Pickfords, Chaplin & Horne undertook a considerable portion of the inland carrying trade. William Chaplin died in 1859 and the business was subsequently acquired by Pickfords.

The Spread Eagle remained in the hands of the Chaplin family until it was sold by auction as prime development land. The building was demolished in 1865.

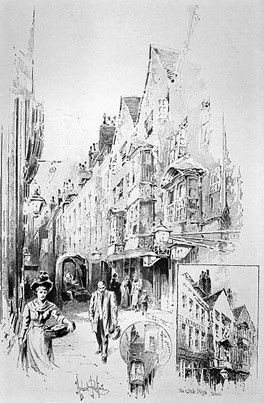

The Swan with two Necks

The Swan with Two Necks is first mentioned in 1556. It was on a short street called Lad Lane which was later incorporated into Gresham Street. Its name was a corruption of the “Swan with Two Nicks”. Swans that swam the upper Thames and were the property of the Vintners’ Company were identified with two nicks on their bills.

In 1637 John Taylor published his guide book, ‘Carriers’ Cosmographie’. Carriers of Manchester come every second Thursday at the two-necked Swan in Lad Lane. Carriers that do pass through diverse other parts of Lancashire lodge there. Carriers of Stafford and other parts of that county come on Thursdays.

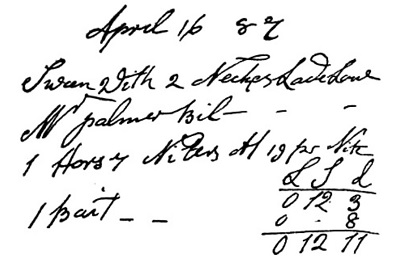

The pioneer of the Post Office in England was John Palmer. He was staying at the Swan with Two Necks in 1787.

His bill shows he was paying one shilling and ninepence a night

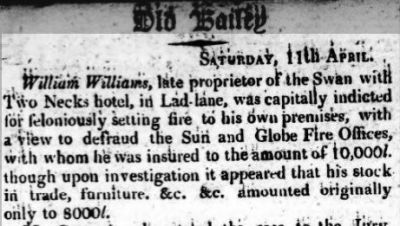

In 1807 the owner ended up at the Old Bailey for an insurance scam.

As a London coaching inn it became famous for the dozens of post and other services running to destinations across the country. It is perhaps most associated with services to the north west, but the many Royal Mail destinations included Hull via Peterborough and Lincoln. Chaplin (who also operated the Spread Eagle) acquired the Swan in 1831 and it became his primary location.

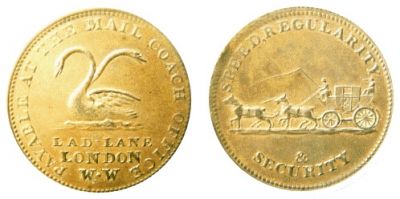

Tokens in the form of half pennies were privately minted in the early 19th century to counter a shortage of small coins. One issuer was the main Mails contractor, William Waterhouse. One of his coins features the Swan with Two Necks:

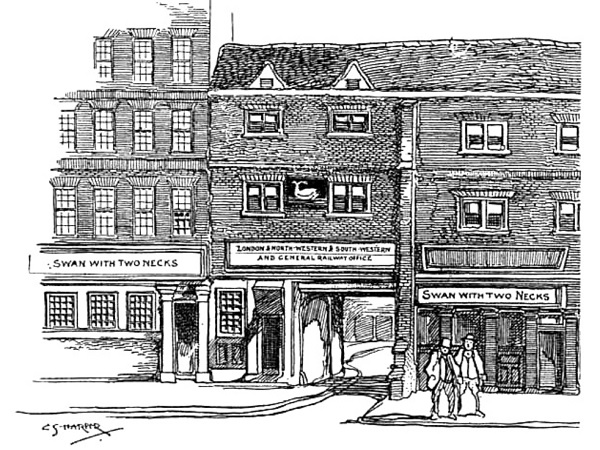

Sketch by Harper (born 1863 so presumably based on another source)

The old buildings of the “Swan with Two Necks” were pulled down in the late 1850s to be redeveloped by Chaplin and his business partner Benjamin Home (of The Golden Cross). They constructed a grand warehouse (with stabling). This was the receiving office ‘for Goods for the Great Eastern, London & South Western, South Eastern, London, Brighton & South Coast & London, Chatham & Dover Railway Companies’. It later became the head office of Pickfords which acquired the business.

The White Horse Tavern

The White Horse is best remembered from an 1857 oil painting by James Pollard which shows the Cambridge Telegraph Coach. The inn was present by 1766 and there are suggestions of origins in the 16th century. At one time it was also known as the Oxford House as it was a starting point for stage coaches to Oxford. By 1819 coach departures included towns the length of the Great North Road but also many other destinations including Arundel and the Isle of Man. The yard provided stabling for over 70 horses, and there were lodgings for both long and short-term visitors to the capital.

In the 1830s it came under the ownership of coaching entrepreneur William Chaplin and later in the century the property is described as the White Horse General Railway Receiving House.

Harper’s description of it is unflattering:

“in Fetter Lane, remained the “White Horse” coaching inn; very much down on its luck in its last years, but interesting to prowling strangers enamoured of the antique and out-of-date.”

It was rebuilt on a smaller scale in 1899, as the stables were no longer needed. As a pub it survived at 90 Fetter Lane until it was demolished in 1989 to make way for office development. [The offices were sold in 2005 for £35m!]

White Horse, Fetter Lane – in 1896 Illustrated London News

The Peacock Inn

The Peacock Inn c1700 with mail coaches departing. James Pollard, 1823

Next along from The Angel, it was said that all north-bound carriages called at the Peacock. It was the “Watford Junction” or “Parkway Station” of its day enabling travellers from north London to avoid having to find the appropriate London posting house or to decipher elaborate time-tables.

An Islington Council plaque on 11 Islington High Street records it as the site of the Peacock Inn from 1564 (though evidence suggests the original inn was further north). Around 1700, the new inn was established with a 67 ft frontage creating a near complete run of three inns.

The Peacock fared less well than the neighbouring Angel towards the end of the coaching era. Reduced in size and re-modelled it survived as a pub, finally closing in 1962.

The Angel, Peacock and White Lion on the west side of High Street Islington. Image credit: Tallis’s London Street Views, 1838–40 (Modern numbering and indications of the extent of the former inns have been added)

A remnant of the Peacock Inn still survives as a tortilla outlet. Image Credit – Google

The White Lion was the Peacock’s neighbour to the north. Its sign was photographed for the London Survey Committee before rebuilding in 1898.

Whilst its name may not live on in the same way as the Angel, a nearby pub still pays homage and the historic inn is well remembered by travellers and writers of its time.

The inn features in Tom Brown’s Schooldays as the inn at which Tom stays prior to travelling to Rugby School.

Tom had never been in London, and would have liked to have stopped at the Belle Savage, where they had been put down by the Star, just at dusk, that he might have gone roving about those endless, mysterious, gas-lit streets, which, with their glare and hum and moving crowds, excited him so that he couldn’t talk even. But as soon as he found that the Peacock arrangement would get him to Rugby by twelve o’clock in the day, whereas otherwise he wouldn’t be there till the evening, all other plans melted away, his one absorbing aim being to become a public school-boy as fast as possible, and six hours sooner or later seeming to him of the most alarming importance.

Tom and his father had alighted at the Peacock at about seven in the evening; and having heard with unfeigned joy the paternal order, at the bar, of steaks and oyster-sauce for supper in half an hour, and seen his father seated cozily by the bright fire in the coffee-room with the paper in his hand, Tom had run out to see about him, had wondered at all the vehicles passing and repassing, and had fraternized with the boots and hostler, from whom he ascertained that the Tally-ho was a tip-top goer—ten miles an hour including stoppages—and so punctual that all the road set their clocks by her.

Then being summoned to supper, he had regaled himself in one of the bright little boxes of the Peacock coffee-room, on the beef-steak and unlimited oyster-sauce and brown stout (tasted then for the first time—a day to be marked for ever by Tom with a white stone); had at first attended to the excellent advice which his father was bestowing on him from over his glass of steaming brandy-and-water, and then began nodding, from the united effects of the stout, the fire, and the lecture; till the Squire, observing Tom’s state, and remembering that it was nearly nine o’clock, and that the Tally-ho left at three, sent the little fellow off to the chambermaid, with a shake of the hand (Tom having stipulated in the morning before starting that kissing should now cease between them), and a few parting words:

The Peacock is mentioned in Charles Dickens’ Nicholas Nickleby as the place where Nicholas stops on his coach journey to Yorkshire, and also in the following extract of Dickens’ Holly-Tree Inn:

When I got up to the Peacock—where I found everybody drinking hot purl, in self-preservation—I asked, if there were an inside seat to spare?1 I then discovered that, inside or out, I was the only passenger. This gave me a still livelier idea of the great inclemency of the weather, since that coach always loaded particularly well. However, I took a little purl (which I found uncommonly good), and got into the coach. When I was seated, they built me up with straw to the waist, and, conscious of making a rather ridiculous appearance, I began my journey.

It was still dark when we left the Peacock. For a little while, pale uncertain ghosts of houses and trees appeared and vanished, and then it was hard, black, frozen day. People were lighting their fires; smoke was mounting straight up, high into the rarefied air; and we were rattling for Highgate Archway over the hardest ground I have ever heard the ring of iron shoes on.

[Hot purl is a punch containing ale, gin and spices.]

London Inns before the Coaches

Inns such as the Saracen’s Head can trace their origins to well before the coaching era.

In 1282 an ordinance for the safe-keeping of London required aldermen to inspect the “hospicia” to identify who was residing in them. Hospicia was a term which seems to have included long-stay guest houses, academic halls of residence and inns for travellers.

In 1308 the king’s marshalls commandeered hospicia from London citizens in order to lodge the influx of visitors arriving for the coronation of Edward II on Sunday 24th February [they were to be restored to their owners by Thursday].

“Ostel”, “inn” and “brewern” were other terms used, then increasingly inns were described as “on the hoop”. The barrel hoop hanging outside, with a distinctive emblem within, introduced the kind of branding we expect today. Early examples include:

- Pye on the hope (Magpie)

- Mayden en la Hope

- Hospicium vocatum la Sterre on the hoope

It was during the early 14th century that commercial inns first flourished in London then spread to smaller towns across the country. We are familiar with the Tabard in Southwark from the opening pages of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. The primary function of the inns was to provide lodgings and refreshment for both travellers and their horses.

Bifil that in that seson on a day,

In Southwerk at the Tabard as I lay

Redy to wenden on my pilgrymage

To Caunterbury with ful devout corage,

At nyght was come into that hostelrye

Wel nyne and twenty in a compaignye

Of sondry folk, by aventure yfalle

In felaweshipe, and pilgrimes were they alle,

That toward Caunterbury wolden ryde.

The chambres and the stables weren wyde,

And wel we weren esed atte beste.

And shortly, whan the sonne was to reste,

So hadde I spoken with hem everichon

That I was of hir felaweshipe anon,

And made forward erly for to ryse,

To take oure wey ther as I yow devyse.

While convention dictated that travellers should pay only a penny per night for their bed, there was ample scope to charge more affluent visitors for superior rooms, fires, food, drink and stabling. Inns multiplied and expanded: despite the Black Death, a 1384 survey of London innkeepers found 197 establishments. Commercial hire of “hackneys” (both riding -horses and pack-horses) developed hand in hand with the inns.

The importance of inns and alehouses is perhaps reflected in various 14th century decrees. In 1375 it was ordered that no brewer should have a pole bearing his sign which projected more than seven feet over the highway. A 1393 decree by Richard II required that “Whoever shall brew ale in the town for the intention of selling it, must hang out a sign, otherwise he shall forfeit his ale.”

Commercial carrier services to and from towns across the country were increasing by the early 15th century. In the 1420s Henry Notyngham of Lynn writes of a carrier who travels weekly from Norwich to London where he stays at “Rossamez Inn, St Lawrence Lane. It is likely that the arched gateways and large yards characteristic of the later inns would be starting to appear.

More Information about London Coaching Inns

Great North Road – Coaching Inns

Medieval Travel – Essays from the 2021 Harlaxton Symposium

[Martha Carlin: Horses & the Rise of Inns in Medieval England

Laura Wright: Vocabulary for Premises used by Travellers in Chaucer’s London]