Road Building Revolution and the Great North Road

For many, many, centuries after the departure of the Romans the approach to road building and maintenance in Britain was piecemeal and pragmatic. Wheeled vehicles were the exception so there was little motivation to provide a broad and solid surface. It was accepted that many journeys could only be made in the dryer months.

Things were starting to change by the 18th century. On major routes such as the Great North Road a regular postal system was established, stage-coach services were appearing and transport of heavy goods such as coal was increasing. The state of roads was clearly inadequate for the ever-greater number of carriages and wagons. The growth of turnpikes after 1700 started to provide funding for investment but it was the road building revolution of the late 18th and the 19th centuries which transformed the road system. The contribution of a few individuals to road building technology made an enormous impact.

In 1754 the journey time for the London to Edinburgh mail coach was advertised as “10 days in summer; 12 days in winter”. By 1832 the journey was taking “42 hours 33 minutes”.

About the Road Building Revolution

Revolution or Evolution?

In reality, the improvements in roads took place over many decades, and there were steps along the way. The early approaches were fairly crude attempts to pile stones into areas of mud. The breakthroughs were brought about through careful engineering of road foundations with particular attention to drainage. The later refinements addressed the need for a hard-wearing top surface, ultimately with the use of bitumen and asphalt to create a smooth and waterproof skin.

These improvements were certainly evident along the Great North Road but not uniquely so. Similar new technologies were being applied to roads across Britain, and indeed in France, the USA and elsewhere.

John Metcalf

Born in 1717, John Metcalf was also known as Blind Jack of Knaresborough. He lost his sight to small-pox as a child but led an active life and operated a carrier business in Yorkshire. Following the 1765 Turnpike Act for the Boroughbridge to Harrogate road Metcalf took up the role of road building contractor. Over the next 30 years he was responsible for re-building some 180 miles of roads and associated bridges. Where conditions were boggy he would pile stones pile stones on top of rafts made from heather, furze (gorse) and brushwood.

Portrait in 1795 biography of John Metcalf. Sketch by JR Smith

John Smeaton

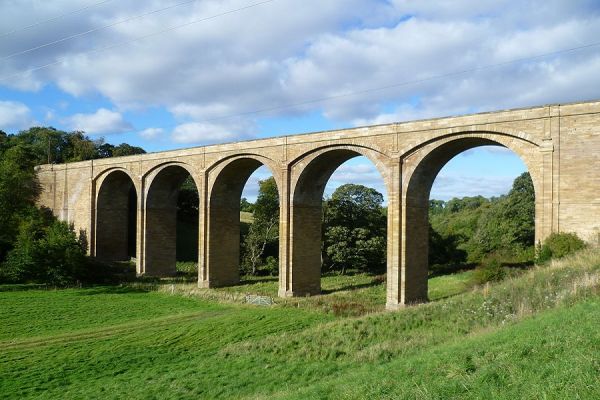

Smeaton was an innovator drawn into road engineering. Born in 1724 he started his career as an inventor and manufacturer of navigation instruments. In his 30s he turned increasingly to civil engineering; he was responsible for the Eddystone lighthouse and worked on the Forth and Clyde Canal. In 1770 he built the Great North Road viaduct at Newark and in 1776 the six-arched bridge over the Tweed at Coldstream.

Thomas Telford

Telford started his working life as a stone mason for Edinburgh’s New Town in the 1770s, worked on Admiralty construction projects in Portsmouth, was county surveyor for Shropshire, and became heavily involved in canal construction for 40 years.

Road building became one of his many specialisms, using a method he developed from that detailed in 1775 by French road engineer, Pierre-Marie-Jérôme Trésaguet. The need for good drainage was part of the solution but the key feature was a 7 inch sub-base of large stones designed to spread the load and reduce deformation of the ground. A second 7 inch layer of coarse broken stone was topped with gravel or more finely broken stone. He developed guidelines on gradients, too, looking to keep inclines to no more than 1 in 30.

A well-preserved section of a Telford road. Image Credit: roads.org.uk

Continuing the work started in the Scottish Highlands by General George Wade and William Caulfeild he is said to have built 900 miles of roads and 1,200 bridges north of the border. Elsewhere, and perhaps most famously, he was responsible for the Holyhead road, including the Britannia Bridge over the Menai Strait. He made major improvements to the Carlisle to Glasgow road and, having done so, proposed improvements to the Morpeth-Coldstream-Edinburgh route.

The dramatic Pathhead bridge (on the now A68) about 11 miles south of Edinburgh. Image credit: Kim Traynor, CC BY-SA 3.0 DEED

In the 1820s his sights turned to wholesale re-engineering of the Great North Road further south but these plans were dropped once the effectiveness of rail transport started to be demonstrated.

John McAdam

In contrast to Telford’s humble origins John Loudon McAdam was born in 1756 to a wealthy family. His father owned the Bank of Ayr but the bank failed and his father died; John was sent to stay with his uncle in the USA where he developed a successful business career. This spell was cut short by the War of Independence after which McAdam returned to Scotland. He experimented with road construction on his family’s Ayrshire estate but it was in 1801 that his road-building career took off when he was appointed surveyor to the Bristol turnpike trustees. Twenty years later he was consulting surveyor to about 70 trusts, many of which were managed by the McAdam family. In 1827 he assumed even greater prominence as the General Surveyor of Roads.

McAdam in about 1830.

The success of his road building was in large measure down to simplicity. He documented this in his 1820 publication, Remarks on the Present System of Road Making:

..it is the native soil which really supports the weight of traffic: that while it is preserved in a dry state, it will carry any weight without sinking, and that it does in fact carry the road and the carriages also; that this native soil must previously be made quite dry, and a covering impenetrable to rain must then be placed over it, to preserve it in that dry state; that the thickness of a road should only be regulated by the quantity of material necessary to form such impervious covering, and never by any reference to its own power of carrying weight.

The over-riding concern becomes drainage and the need for a sophisticated base layer is avoided. As with Telford’s roads, McAdam used crushed stone to create the water resisting top layer. McAdam’s roads did not use tar. The camber needed to be carefully gauged – though he advocated less of a slope than used by others; this was to discourage coaches from always looking to follow the same central section of the road in order to keep upright.

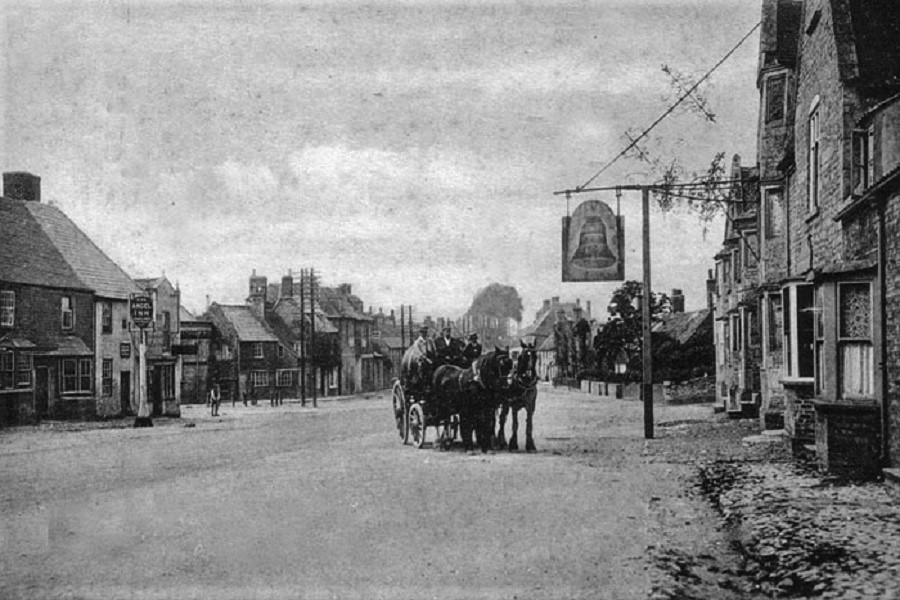

Early photo of a “Macadam Road” from around 1850 in North America. The main photo at top of page shows the Great North Road with a similar surface in Stilton at about the turn of the 20th century.

New Surfaces in Towns and Cities

Road surfaces through the towns had been a source of much anguish for centuries. Cattle markets, butchers, absence of proper drains, and rising population resulted in smelly, muddy and unhygienic conditions. By the 18th century efforts were being made by newly formed local authorities to make improvements. An archaeological study of Peterborough market square revealed a succession of new surfaces laid over putrid medieval layers.

In the 19th century London was regularly experimenting with innovative new surfaces to find those that might cope with the heavy traffic. A 12 hour vehicle count along Ludgate Hill in March 1843 recorded 1,516 one-horse carts, 1,238 cabs and gigs, 1,174 omnibuses and stages, 990 other vehicles, 204 horses and 80 hand-trucks.

McAdam noted that:

“the gravel of which the roads around London are formed is the worst; because it is mixed with a large proportion of clay, and because the component parts of gravel are round, and want the angular points of contact, by which the broken stone unites and forms a solid body; the loose state of the roads near London, is a consequence of this quality of material, and of the entire neglect, or ignorance of the method of amending it.”

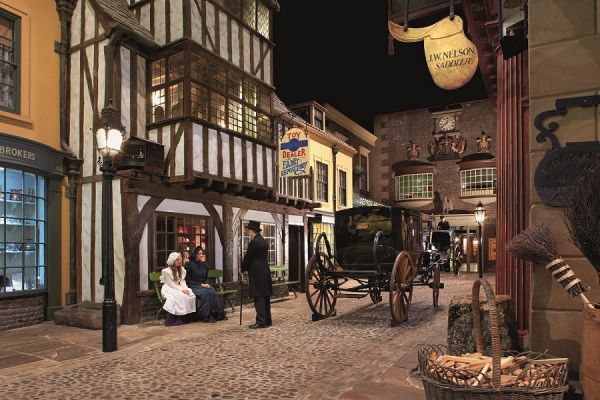

Surfaces of gravel and natural rounded cobbles were progressively (and sometimes repeatedly) replaced with granite setts.

A cobbled street re-created at York Castle Museum

Once the best sources of rock and methods of laying had been determined, granite setts were a hardwearing solution. However, there were regular complaints about noise and dust. Towards the end of the century wooden setts and asphalt surfaces started to prevail though granite was retained for more demanding situations.

Bitumen and Asphalt

Bitumen (or pitch) is a naturally occurring black, viscous hydrocarbon, used as an adhesive and sealant since pre-history. Tar can be derived from bitumen (and other hydrocarbons) through distillation. The term asphalt is reserved (in Britain) for mixtures containing both bitumen and construction aggregates.

There is no evidence for the use of bitumen and asphalt for road building before the 19th century (with the possible exception of the processional way in ancient Babylon where large stones were laid in a bed of bitumen). There were then multiple experiments in France, Britain and the USA.

One of the earlier examples was Huntingdon High Street where a tarred gravel surface was introduced in 1845. The first record of a significant road being constructed with impervious material was that from Paris to Perpignan in 1852, using Swiss Val de Travers ‘rock asphalte’ (a limestone impregnated with bitumen). In London, Threadneedle street was paved with compressed asphalt in 1869; the new surface could be very slippery when damp. A report in the New York Sun:

“Several other varieties of asphalt pavement have been tried, but the Val de Travers is the only one that has come into extensive use. It is as smooth as marble slabs and not noisy, and the only objection to it comes from horse owners, members of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, and the horses themselves.”

During the 1870s Edward de Smedt patented an asphalt pavement which was laid on Fifth Avenue, New York and Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington.

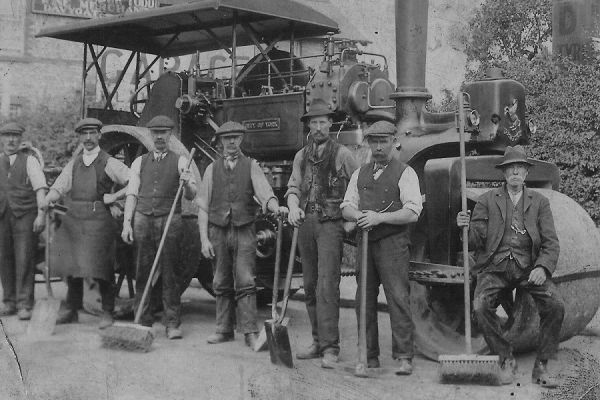

‘Tarmac’ was a form of asphalt patented in 1901 by British civil engineer Edgar Purnell Hooley. He mixed tar, aggregate, and cement resin before laying the material and compacting it with a steam roller. The timing was right since the ‘water-bound’ roads of the past were being rapidly turned to dust by the new motorcars.

Kent was a pioneering county within Britain and by 1911 was spending nearly £30,000 a year on tar spraying and on repairing its roads with bitumen and tar. The county surveyor, Henry Maybury, reported that local roadbuilding materials were not strong enough to withstand the increasing volume and speed of motor traffic, and that the passing of `light cars’ was accompanied by `a shower of flints.’

“Granite was imported at great cost from outside the county to create stronger surfaces, only to crumble under the assault of the anti-skid studs that motorists were now fitting to their tyres; the studs `cut right through the granite surface, leaving saucer-shaped holes which are extremely difficult to repair.”

York’s third Aveling Barford steam roller. Image Credit – Bob Cook