Medieval Transport and the Great North Road

Knowledge of medieval transport is decidedly patchy. There are precious few maps before that of Ogilby in the 17th century so we have to piece together the picture from scraps: historical records of specific journeys made or goods conveyed; records relating to specific bridges or improvements to roads or rivers; deduction from the growth of specific towns or industries.

There was significant evolution of transport systems during the 700 years from 800 to 1500AD. There was a transition to use of horses rather than oxen. There were innovations in horseshoes, harnesses, horse breeding, wheels, carts and bridge building. Navigability of rivers was impeded by increasing numbers of mills and weirs. There was increasing trade and industry and a gradual commercialisation of the economy. Our focus is on the evolution and history of the Great North Road but many of the themes are more broadly seen across England – and indeed Europe.

One broad conclusion is that the highest point of navigation of many of the rivers of the east of England diminished. At the same time the network of bridges expanded, first built of wood and later stone, allowing reliable crossing points further to the east.

The Great North Road through Huntingdon was definitely used during the medieval period but it was often not the favoured route from London to the north east in the early years. The 13th century Mathew Paris maps suggest a more westerly route crossing the Great Ouse at Stony Stratford (Milton Keynes) then via Northampton and Leicester. Analysis of the itineraries of the kings of the 13th – 14th centuries (John, Henry III, Edward I & Edward II) shows them more typically passing through Leicester, Nottingham then Doncaster.

A bridge across the Trent at Newark was constructed in the second half of the 12th century, and there was a bridge across the Nene at Wansford by 1221. The late 14th century Gough map shows our familiar Old North Road. By the time Margaret Tudor travelled north to become Queen of Scotland in 1503 the route through Stamford was the obvious choice. Interestingly, the re-established North Road just happened to pass through towns marking the upper limits of river transport such as Wansford, Stamford, and Elkesley – so helping to provide an integrated transport network for the region.

While there had been a return towards the Roman military route during the later medieval period, there were deviations. An example is where the Gough map shows the road passing through Ogerston between Huntingdon and Wansford – a few miles west of the ancient route. This would have reflected a wish to avoid the lower ground close to the Fen edge near Stilton and the demise (many centuries before) of the Roman Nene bridge at Water Newton. [This inland route through Huntingdonshire continued to be used by drovers avoiding the traffic and tolls on the main road and it came to be known as Bullock Road.]

North of Stilton at Water Newton the medieval road (and current A1) kinks west, away from the straight line of Ermine Street, to cross the Nene at Wansford before re-joining the old alignment at Stamford. (Photo Credit – Rex Gibson)

Medieval Transport – Readiness to Travel

Medieval people were surprisingly ready to travel. This is despite the fact that travelling at this time would have brought physical discomfort, navigation challenges, and risk from accidents and crime.

Some made their living by transporting goods in vehicles or boats. Others such as crown and monastic officials had to keep tabs on far flung estates. As traditional ties to the land were eroded some were prepared to travel to find work and opportunity. For many more, the urge to travel was driven by pilgrimage or crusade.

Perhaps the discomforts and risks seemed minor compared to the normal travails of everyday life. Perhaps without the prospects of the holidays we expect, any opportunity to explore the wider world was a bonus. Perhaps the welcome given to strangers and travellers reduced the costs and made travelling an enjoyable activity.

Medieval Pilgrims to the shrine of Thomas Becket (1465-67), John Lydgate, Siege of Thebes ff. 148, British Library

The motivation for pilgrimage in medieval Britain was essentially to encounter God and his saints and find spiritual and practical benefits through that contact. Dee Dyas (Professor of the History of Christianity, University of York):

“Many pilgrims were looking to strengthen their faith or seek forgiveness for sins. Shrines increasingly offered indulgences – a means to gain remission from time spent in purgatory – during the Middle Ages. Some people were sent to particular holy sites as a punishment for serious sins. And in an age where medicinal cures were few, many people embarked on pilgrimages in search of healing, either for themselves or for family and friends. Women wanting to conceive made up a large number of these.”

A medieval manuscript found in the Durham monastic library describes how the heavy, painted cover hiding the shrine containing the relics of St Cuthbert would have been lifted. As the canopy slowly ascended, six attached silver bells rang out and the Magnificat was sung. Covered with gold, intricate figures and masses of rich jewels, the feretory would have been incredible to behold.

Then, as before and since, pilgrimage was theatrical and carefully orchestrated.

Medieval Transport – Maps & Itineraries

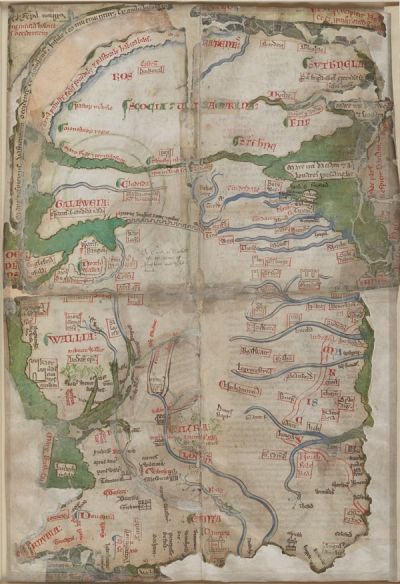

A stepping stone towards the maps of today was created in the 13th century by Matthew Paris, a monk at St Albans. His maps retain east at the top of the map but there is moderately reliable identification of towns and rivers. There is little representation of roads though the route north through England is a virtual straight line across the middle of the map.

Matthew Paris’ Map of Britain, from a collection of historical works, c. 1255-1259, St Albans (Cotton MS Claudius D VI/1)

A second step came with what is known as the Gough map. Its exact date and author are not known but it is believed to date from the late 14th century. London and York are the most prominent towns, highlighted with gold leaf. There is generally more detail and what might be described as roads are indicated between some of the towns, along with distances measured in leuga (about 10 furlongs). The routes radiating from London include one to Carlisle.

“London XII Waltham Abbey VIII Ware XIII Royston IX Caxton VIII Huntingdon XIII’ Ogerston V Wansford V Stamford XVI Grantham X Newark X Tuxford X Blyth VIII Doncaster X Pontefract XX Wetherby VIII Boroughbridge XIIII Leeming X Gilling X Bowes XIII Brough XI Appleby X Pehrith XVI Carlisle.”

There are also “itineraries” being written down as longer distance travel becomes more commonplace. These list the waypoints of a journey and may include distances and other route guidance. A good example are those of about 1400 from Tichfield Abbey in Hampshire to other houses of Premonstratension Canons the length of the country including Shap and Alnwick. The route to Alnwick is via Leicester, Worksop and York.

It is only in the 17th century that publications such as Ogilby’s road maps of England and Wales give the kind of accuracy and detail we expect of a road atlas.

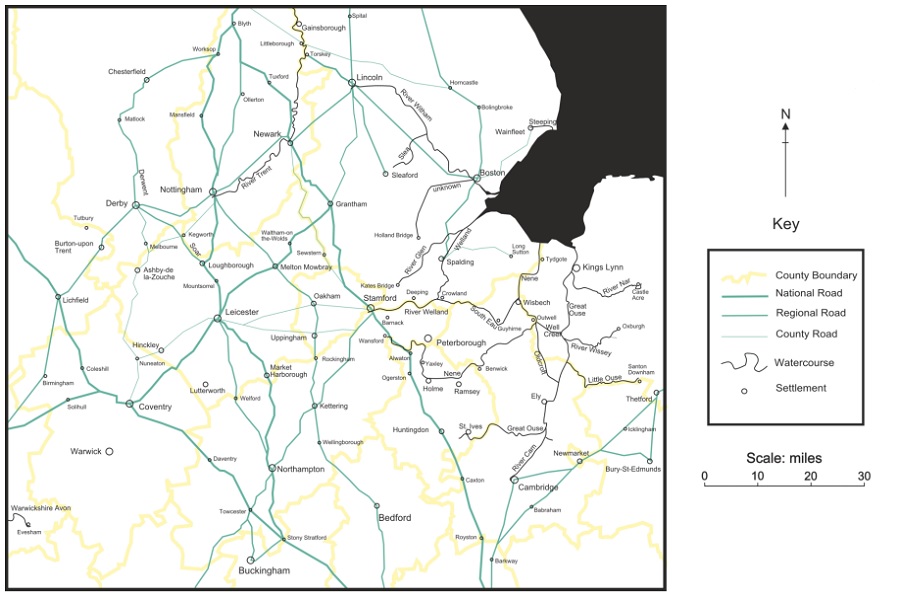

Evan Jones has sought to consolidate the information from the maps and other sources:

“While there is evidence to suggest that the importance of individual roads changed between 1360 and 1675, the actual line taken by particular roads seems to have altered little over this period. This becomes obvious when those roads that are detailed in both the Gough map and the Ogilby survey are examined…. In every case where a comparison is possible, the line taken by individual roads was almost exactly the same in 1675 as it was in 1360. The most likely reason for this is that there was little new investment in road transport infrastructure between the late medieval period and the 18th century. As a result, very few new road bridges were built during the early modern period and in general it appears that the road transport infrastructure of the early modern period was largely high medieval in origin.”

Late Medieval Roads & Rivers in the East Midlands, Evan Jones

Medieval Bridges

Medieval bridge replacement – artists re-construction, Tomas Honz

Whilst the evidence of transport networks from maps is scant, there is a lot more evidence about medieval bridges. The crossing points of rivers are of practical and strategic importance. Their location has a major impact on the routing of transport and the prosperity of towns. They have always been expensive both to build and to maintain – so records often survive.

The Romans built virtually no stone arched bridges. They bridged major rivers but the technique was usually to use stone piers to carry wooden beams, which in turn supported a wooden carriageway. However well constructed these would have limited life unless regularly maintained. In reality, many of the engineering skills quickly dissipated, and without a central governing body the system of river crossings reverted to the norms that had previously existed – fords and ferries.

A new era of bridge building was on the move by the 9th and 10th centuries. Evidence includes references to them in an increasing number of Anglo Saxon charters. It was at a time when the network of Burhs was developing, and more centralised administration evolved. The liability to build and repair bridges became more important. Often strategic issues came into play; the Anglo Saxon chronicle records the building of a bridge over the Trent at Nottingham at about the time Edward the Elder went there with an army in 920AD (a bridge downstream on the Trent would not be built for another 200 years). The bridge at Huntingdon was also built at this time when Edward also ordered construction of the nearby castle.

A bridge over the Thames in London was built in about 1000AD. Though not recorded until a century later it is likely that the bridges at Stamford and York were products of the 10th centuries. William’s securing of the conquest is also likely to have had an effect; he did not want to repeat his frustration of 1069 when his way north to York was blocked at Pontefract (broken bridge) where the River Aire was swollen by heavy rain. By the end of the 13th century other bridge projects included Stratford (Lea), Newark (Trent), Croft (Tees), Durham (two over the Wear), Hexham (Tyne) and Berwick (Tweed). This period also saw construction of causeways across flood plains, important for roads since rivers were less confined to narrow channels and more likely to flood.

David Harrison has provided the most authoritative perspective on medieval bridges and, based on good historical documentation for certain rivers such as the Great Ouse and the Thames, his view is that:

“The majority of the pre-industrial bridge network had been built by the first half of the 13th century”

“Many of these new bridges were on different sites from those of the Roman river crossings. Together with major new centres, they were the focal points of a new road system which was significantly different from the Roman network.”

An exception to the pattern of fewer new bridges was that over the Great Ouse at Barford built in about 1430. This was instrumental in opening up the Hertfordshire-Bedfordshire route of the Great North Road – gradually displacing the Old North Road via Royston.

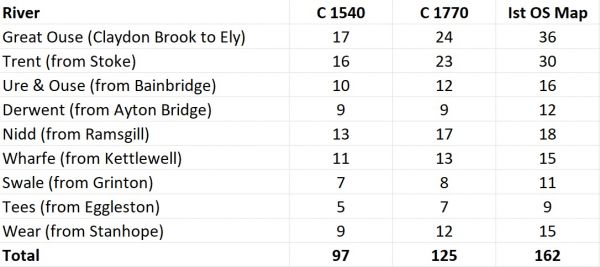

Number of Known Bridges (Selected Rivers)

After Harrison, The Bridges of Medieval England

Whilst bridges were present at many of the key crossing points by 1300 these were often still constructed of wood and regular repair and replacement was necessary. When bridges failed it might take several years (or decades) for a new one to take its place necessitating significant diversion of traffic.

Huntingdon bridge is a well documented example. In 1276 it was “so broken that it is almost impassable for passengers on horseback or on foot”. It was destroyed by flood waters laden with ice during the winter of 1293-4. It was rebuilt at the turn of the century but within 30 years it was again described as being in a “ruinous state”. The six arched stone bridge which is still in use dates from this time. As well as the new bridge, permission was granted to build a causeway across the king’s land from the bridge to Godmanchester.

The Barford bridge over the Great Ouse from about 1440 (partially obscured by later widening)

Medieval Transport – Rivers v Roads

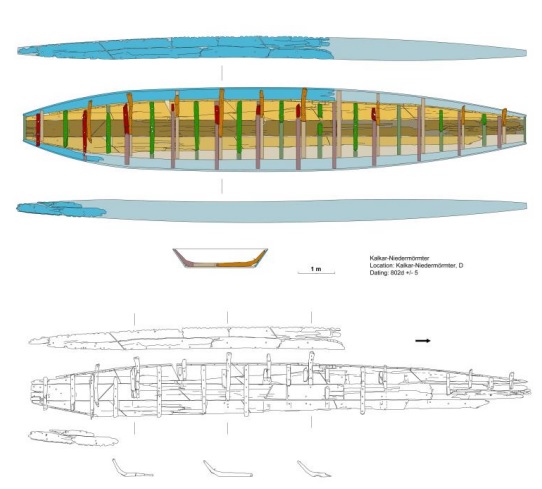

14m long River Barge from Kalkar-Niedermörmter, 800AD

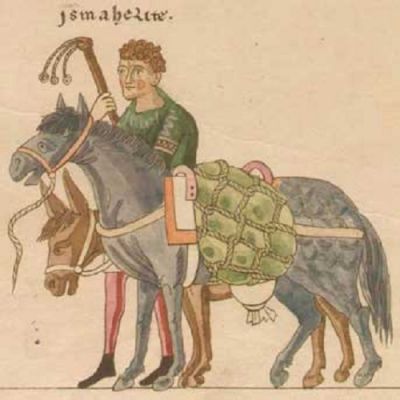

12th century illumination showing pack animals – a mule and a donkey with driver on foot

Road transport for both people and goods increased in importance relative to river transport during the medieval period, but the balance between roads and rivers was an evolving and complex one. During the early period recent evidence from John Blair suggests the “purposeful and dynamic” improvement of navigable waterways before about 1250 with their “fragmented and incoherent” attrition thereafter. While navigation of rivers was becoming more problematic so the road network was being improved by the construction of bridges, first of wood and later of stone.

An example of declining navigability is the Foss Dyke – a Roman waterway connecting the Witham at Lincoln to the Trent at Torksey. The Foss Dyke was clearly navigable until the 13th century but during the 14th century there is evidence that it became blocked. Renewed efforts to clear obstructions began in 1518 but it was not fully reopened until 1672.

Navigability of rivers was also obstructed by the building of water mills and their associated weirs. There are suggestions that the Great Ouse was formerly navigable as far as Bedford or beyond, based in part on the presence of a 10th century Danish dock at Willington. Others claim only the smallest boats could travel further than St Ives. The different perspectives may purely be down to change over the centuries. A complaint was made in 1287 by merchants that obstructions on the river between St Ives and Huntingdon had blocked the river so “that ships and boats laden with merchandise can no longer pass as they were wont”. This was followed in 1370 by a complaint from merchants of a number of counties about “weirs mills and stanks” built on the river since the time of the King’s grandfather (ie 1272).

Illustration from the Luttrell Psalter (c1325-1345) showing an overshot watermill with fish and eel traps in the millpond

Where available, river transport remained the far cheaper option – particularly with respect to heavy and bulky goods. During the winter of 1258, Henry III granted 34 tuns of wine to Eleanor, his queen. This wine had been imported at Boston and was in store at Peterborough. The King ordered the Sheriff of Cambridge to transport the wine

“to Cambridge with all speed by water, and thence by land to Ware”.

At Ware, responsibility for delivery of the wine was to be undertaken by the Sheriff of Essex and Herts, who was to take the cargo from Ware by water to Westminster. This is a complicated multi-stage journey by today’s standards, involving the Rivers Nene, Great Ouse, Cam, Lea and Thames.

For most goods, water transport would always have been cheaper than land but it is likely that the differential moved in favour of road transport during the period as the network of roads and bridges was consolidated. The equation is complex and there were other factors such as the introduction of versatile and less expensive flat bottomed and clinker sided vessels on the one hand, and the shift towards horses rather than oxen on the other. An estimate by Masschaele based on early 14th century data is that river costs were half those of road, and coastal shipping an eighth.

The reality in many cases would be a hybrid of land and river and coastal transport, giving importance to the towns and hythes where goods were trans-shipped. An indication is given by Uhler who analysed the transportation of produce during the fourteenth century. The evidence for Yorkshire shows that in 1298, 1301 and 1309 grain, corn, oats, malt, flour, barley and peas were shipped to Scotland from Hull, Selby and Yarm. The produce completed the first leg of the journey by cart from a small inland centre to a larger one, from where the journey continued to the leading collection centres in the county, which were closely linked by river with the customs ports.

For people, too, the waterways often remained a viable option. In 1319 a group of 33 Cambridge students were invited to spend time with the King’s household in York. Seven travelled over land on horseback; departing on Thursday 20th December they reached York on Christmas Eve. The others needed to navigate the Great Ouse, Witham, Foss Dyke, Trent and Ouse; they arrived on 28th December having spent Christmas day in Lincoln.

Medieval Transport – Horses

A lot of travellers walked. Many animals walked to market. In the early medieval period any wagons are likely to have been pulled by oxen. However, the trend through the medieval period was towards the use of horsepower.

The numbers of mounted infantry grew in the 9th and 10th centuries, and cavalry came to have a major role in medieval warfare. By the 11th century horses were starting to share the burden of the plough with oxen. By the 12th century, horses had begun to play a more prominent role in the transport of goods. By the 13th century horses were regularly pulling carts.

Quality horses were imported from Spain, Lombardy, and the Low Countries. The primary focus may have been on the warhorse, but the effect of selective breeding was equally felt by the agriculture and transport sectors. Large horse-fairs emerged, serving to improve and distribute the animals. A peasant work horse was very different to a “destrier” warhorse but the upshot was that horses became the primary power source for the medieval economy.

John Langdon investigated the animal-power basis for hauling and carrying on English farms from the 11th to the 15th centuries. Generally speaking over this period, and particularly for the 12th and 13th centuries, there was a significant increase in the use of horses as a replacement for oxen. This was facilitated by the development of the padded horse collar and other associated improvements in horse traction, such as improved wheels designs for lighter and more flexible carts. The increase of hauling speed from about 1½–2 to 3–4 miles per hour by transitioning from oxen to horses seems modest, it had the potential to double the speed of transport.

Stirrups and horseshoes both became the norm during the medieval period. Initially horseshoes were likely to be bronze but iron horseshoes became widespread in the 13th and 14th centuries.

We start to see concerns about the speed of carts and wagons. In what might be the first speeding law, the city of London had this ordinance included in its 15th century Liber Albus:

“no carter within the liberties shall drive his cart more quickly when it is unloaded, than when it is loaded; for the avoiding of divers perils and grievances, under pain of paying forty pence unto the Chamber, and of having his body committed to prison at the will of the Mayor.”

Transport and the Medieval Economy

We know the importance of both local and international trade was increasing. Industries such as wool and cloth became major drivers of prosperity. However, later medieval economic history has long been defined by negativity, with studies focusing upon declining tithe incomes, falling or stagnant populations, declining credit and money supply and falling productivity. More recently, historians have examined the microeconomic detail and a different picture emerges. Per capita incomes were not necessarily falling after the Black Death.

Dyer finds a “hidden trading network” was well established by the 11th century.

“London’s tentacles in the 15th century spread over the whole kingdom…. Even the bishop of Carlisle and the cellarer of Durham Priory bought spices from merchants in the capital.”

Whilst the population of the country was well under a tenth of today’s and urban living very much the exception, the move away from feudal subsistence lifestyles was significant and the importance of trade, travel and transport easy to underestimate.

Medieval Transport – Additional Information

Transport Systems in and Around the East Midlands c1300-1550, Evan Jones

The Bridges of Medieval England, David Harrison, Clarendon Press, 2004

Transport in Medieval England, John Langdon and Jordan Claridge, University of Alberta