Dick Turpin and the Great North Road

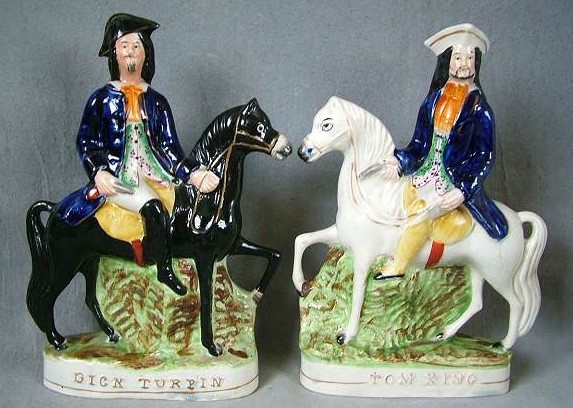

The “Flying Highwayman” was famed for his bravery, resolution and generosity. A scoundrel and a thief but also a gentleman who minimised any harm to those “upon whom he levied his contributions”. Women were attracted by his manly beauty, debonair deportment and extravagant red whiskers.

His beloved coal-black horse, Bess, was legendary. Every point was perfect; beautiful, compact, modelled for strength and speed. Together they were repeatedly able to evade pursuers, leaping locked toll gates and charging the length of the country to establish strong alibis. Alas, despite generous rations of ale poor Bess finally collapsed on the outskirts of York after a 200 mile ride from London in under 12 hours.

Dick Turpin pursued his trade in many of the well known robbery hot-spots between London and York; Epping Forest, Gunnerby Hill (near Grantham) and Thorne (near Doncaster) were amongst his hide-outs.

Charles Harper describes (and draws) an ancient oak at Brown’s Well, Finchley Common. Known as Turpin’s oak, visitors came to see pistol bullets in the trunk fired by travellers just in case it concealed a highwayman.

Dick is associated with many of the coaching inns along the Great North Road.

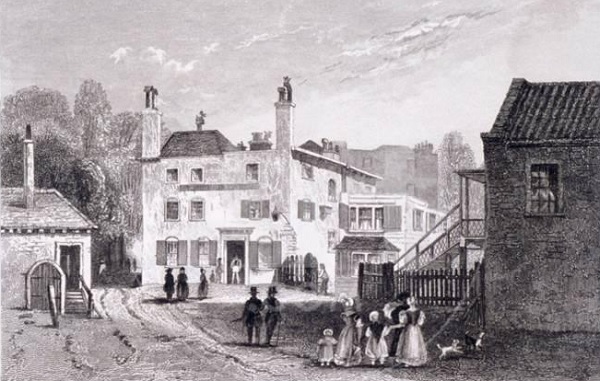

The Spaniards Inn in Hampstead is haunted by Dick Turpin. His father was once the landlord, and the inn was used as a hiding place by Dick. Black Bess was kept at the nearby toll keeper’s cottage where there is a horse trough to this day.

At Stevenage, both the Roebuck and the White Lion were refuges. With other miscreants Dick escaped using tunnels beneath the inns. He hid for 9 weeks at the Bell in Stilton; when forced to leave he leapt from an upstairs window onto the Black Bess who was waiting below.

The Spaniards Tavern, Hampstead

He is even responsible for the naming of the Ram Jam Inn for it was he who incapacitated the publican’s wife by having her “ram” her thumb in a beer barrel whilst “jamming” her other thumb in a hole at the other end.

A little further north a favourite haunt was the Jockey House near Markham Moor. A secret compartment was discovered in the 1960s. This had been used by Dick Turpin when the law was after him.

His most efficient enemies were the Bow Street Runners. One narrow escape involved him taking the Cawood Ferry across the Ouse (between Tadcaster and Selby).

Dick Turpin defying the Bow Street runners

Eventually his criminal tendencies caught up with him after he accidentally killed a friend whilst trying to save his life in a gun fight. He remained refined and distinguished to the last. His gaoler earned £100 selling drinks to Turpin and his guests.

His body was taken from the gallows in York to his final resting place at the Blue Boar. His ghost is regularly seen there. A prominent headstone was erected nearby.

One of Dick Turpin’s great journeys from London to York is commemorated in the following ballad by Alfred Noyes:

The daylight moon looked quietly down

Through the gathering dusk on London townA smock-frocked yokel hobbled along

By Newgate, humming a country song.Chewing a straw, he stood to stare

At the proclamation posted there:“Three hundred guineas on Turpins head,

Trap him alive or shoot him dead;And a hundred more for his mate, Tom King.”

He crouched like a tiger about to spring.Then he looked up, and he looked down;

And chuckling low, like a country clown,Dick Turpin painfully hobbled away

In quest of his inn – “The Load of Hay”…Alone in her stall, his mare, Black Bess,

Lifted her head in mute distress;For five strange men had entered the yard

And looked at her long, and looked at her hard.They went out, muttering under their breath;

And then – the dusk grew still as death.But the velvet ears of the listening mare

Lifted and twitched. They were there – still there;Hidden and waiting; for whom? And why?

The clock struck four, a set drew nigh.It was King! Dick Turpins’ mate.

The black mare whinnied. Too late! Too late!They rose like shadows out of the ground

And grappled him there, without a sound.“Throttle him – quietly – choke him dead!

Or we lose this hawk for a jay, they said.”They wrestled and heaved, five men to one;

And a yokel entered the yard, alone;A smock-frocked yokel, hobbling slow;

But a fight is physic as all men know.His age dropped off, he stood upright.

He leapt like a tiger into the fight.Hand to hand, they fought in the dark;

For none could fire at a twisting mark.Where he that shot at a foe might send

His pistol ball through the skull of a friend.But “Shoot Dick, Shoot” gasped out Tom King

“Shoot! Or damn it we both shall swing!Shoot and chance it!” Dick leapt back.

He drew. He fired. At the pistols crackThe wrestlers whirled. They scattered apart

And the bullet drilled through Tom King’s heart…Dick Turpin dropped his smoking gun.

They had trapped him five men to one.A gun in the hand of the crouching five.

They could take Dick Turpin now alive;Take him and bind him and tell their tale

As a pot house boast, when they drank their ale.He whistled, soft as a bird might call

And a head rope snapped in his birds dark stall.He whistled, soft as a nightingale

He heard the swish of her swinging tail.There was no way out that the five could see

To heaven or hell, but the Tyburn tree;No door but death; and yet once more

He whistled, as though at a sweethearts door.The five men laughed at him, trapped alive;

And – the door crashed open behind the five!Out of the stable, a wave of thunder,

Swept Black Bess, and the five went under.He leapt to the saddle, a hoof turned stone,

Flashed blue fire, and their prize was gone…Away, through the ringing cobbled street, and out by the Northern Gate,

He rode that night, like a ghost in flight, from the dogs of his own fate.By Crackskull Common, and Highgate Heath, he heard the chase behind;

But he rode to forget — forget — forget — the hounds of his own mind.And cherry-black Bess on the Enfield Road flew light as a bird to her goal;

But her Rider carried a heavier load, in his own struggling soul.He needed neither spur nor whip. He was borne on a darker gale.

He rode like a hurricane-hunted ship, with the doom-wind in her sail.He rode for one impossible thing; that in the morning light

The towers of York might waken him — from London and last night.He rode to prove himself another, and leave himself behind.

And the hunted self was like a cloud; but the hunter like the wind.Neck and neck they rode together; that, in the day’s first gleam,

each might prove that the other self was but a mocking dream.And the little sleeping villages, and the breathless country side

Woke to the drum of the ghostly hooves, but missed that ghostly ride.The did not see, they did not hear as the ghostly hooves drew nigh,

The dark magnificent thief in the night that rode so subtly by.They woke, they rushed to the way-side door, They saw what the midnight showed,—

A mare that came like a crested wave along the Great North Road.A flying spark in the formless dark, a flash from the hoof-spurned stone,

And the lifted face of a man – that took the starlight and was gone.The heard the sound of a pounding chase three hundred yards away

There were fourteen men in a stream of sweat and a plaster of Midland clay.The starlight struck their pistol-butts as they passed in the clattering crowd

But the hunting wraith was away like the wind at the heels of the hunted cloud.He rode by the walls of Nottingham, and over him as he went

Like ghosts across the Great North Road, the boughs of Sherwood bent.By Bawtry, all the chase but one has dropped a league behind,

Yet, one rider haunted him, invisibly, as the wind.And northward, like a blacker night, he saw the moors up-loom

And Don and Derwent sang to him, like memory in the gloom.And northward, northward as he rode, and sweeter than a prayer

The voices of those hidden streams, the Trent, and Ouse and Aire;Streams that could never slake his thirst. He heard them as they flowed.

But one dumb shadow haunted him along the Great North Road.Till now, at dawn, the towers of York rose on the reddening sky.

And Bess went down between his knees, like a breaking wave to die.He lay beside her in the ditch, he kissed her lovely head,

And a shadow passed him like the wind and left him with his dead.He saw, but not that one as wakes, the city that he sought,

He had escaped from London town, but not from his own thought.He strode up to the Mickle-gate, with none to say him nay.

And there he met his Other Self in the stranger light of day.He strode up to the dreadful thing that in the gateway stood

And it stretched out a ghostly hand that the dawn had stained with blood.It stood as in the gates of hell, with none to hear or see,

“Welcome,” it said, “Thou’st ridden well, and outstript all but me”.

About Dick Turpin

All of the above is utter nonsense. Fake news is not such a new phenomenon. Even the pamphlets which circulated and informed the newspaper reports immediately after his death contained inaccuracies. The drivers and guards on the stage-coaches peddled more and more outlandish stories in return for applause and tips. Inn keepers were always after ways to build the reputation of their establishments. And by the time William Harrison Ainsworth wrote his popular gothic novel, Rockwood, facts were never going to interfere with a first-class adventure yarn which could rival James Bond. Repeated regularly over the centuries, it is this web of fantasy which has come to characterise Dick Turpin.

Dick Turpin was born on 21st September 1705 in Hempstead, Essex (east of Saffron Walden), not in Hampstead.

His father was indeed an inn keeper and also a butcher. Dick became apprenticed as a butcher in London.

In about 1725 he married Elizabeth Millington.

In the early 1730s he was able to combine his butchery skills with membership of the “Essex Gang” which specialised in the theft of deer from Epping Forest. By 1734 this group was undertaking regular armed burglaries in and around London. They regularly featured in newspaper reports and named members assumed notoriety. While many of his accomplices were apprehended and executed or deported, Turpin managed repeatedly to escape.

He was first named as a suspect in a case of highway robbery following an attack on 12th July 1735. His involvement in further robberies on Barnes Common, Putney, Kingston Hill and Hounslow Heath were reported in the following months.

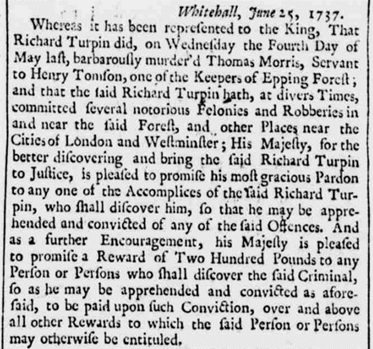

In 1737 he was working with two other highwaymen, Stephen Potter and Matthew King (dubbed Tom King in later accounts). Following a string of robberies they were spotted and King was fatally shot, though not by Turpin as initially reported. Turpin sought refuge in Epping Forest, then shot and killed a gamekeeper who recognised him. A £200 price was put on his head.

Stamford Mercury – Thursday 30 June 1737

By this time there were regular newspaper reports where Turpin was accused of robberies, or of being seen as far afield as Holland and Scotland.

E-fit of Turpin produced by North Yorkshire police provided forensic specialists in 2009

Turpin fled north and assumed a new identity as John Palmer. He visited his father in July 1737 riding a horse stolen from Pinchbeck; he stole 3 more on his return trip. It is for these horse thefts that he was ultimately hanged. He is known to have lived 9 months at Long Sutton in Lincolnshire but was accused of sheep stealing and moved on. He was later posing as a horse trader in the East Riding of Yorkshire. Following an altercation in 1738 he was committed to the House of Correction at Beverley. Depositions provided to local justices making enquiries into Palmer’s background suggested he was guilty of horse stealing (a capital offence). This prompted a transfer to York Castle.

It was only the chance interception of a letter sent to his brother-in-law which caused Turpin’s true identity to be revealed. The handwriting was recognised by James Smith, who had taught his younger schoolmate to write; Smith travelled to York Castle to identify him and successfully claimed the £200 reward.

At his trial Turpin repeatedly claimed that proceedings should be delayed until he could call his witnesses, and that the trial should be held at Essex. The judge did not agree and he was sentenced to death.

His plight certainly did attract publicity and it is true that Turpin demonstrated a certain swagger. He bought a new frock coat and shoes, and on the day before his execution hired five mourners for three pounds and ten shillings.

Along with another horse thief he was taken to the Knavesmire on 7th April. He was led to the gallows by a pardoned highwayman, York at that time having no permanent hangman.

“Turpin behaved in an undaunted manner; as he mounted the ladder, feeling his right leg tremble, he spoke a few words to the topsman, then threw himself off, and expir’d in five minutes.”

The Gentleman’s Magazine

His body was indeed taken to the Blue Boar tavern in Castlegate, York but he was buried opposite St George’s near Walmgate Bar. His body almost fell prey to grave robbers, with Marmaduke Palms (York surgeon) bound over for the offence. The large headstone which can be seen today was erected after 1918 to boost the tourist trade – and is probably in the wrong place.

The Bow Street Runners were formed in 1749 and can never have had any involvement with Turpin.

The sprint from London to York is in all likelihood borrowed from the life of another highwayman, John Nevison who established an alibi in this way some years earlier.

In appearance Turpin was described by a former associate as

“a fresh coloured man, very much marked with the small pox, about five feet nine inches high, his cheek-bones broad, his face thinner towards the bottom, his visage short, pretty upright, and broad about the shoulders.”

Though not a comprehensive list, none of Dick Turpin’s highway robberies mentioned above took place on the Great North Road.

Turpin’s more recent biographer, James Sharpe:

“Turpin was a hard man capable of acts of cruelty, who had an uncertain temper and was prone to violence, who had no reservations by the end of his career about using firearms, and who also far from being the daredevil of later fiction, knew when the best policy was to cut and run.”

Execution day in York, Thomas Rowlandson, 1820. The prison wagon with the condemned and their coffins passes through Micklegate on the way from York Castle Gaol to Knavesmire. (Image credit: York Museums Trust)

More Information about Dick Turpin

Dick Turpin – The Myth of the English Highwayman, James Sharpe

Top of page image: Dick Turpin’s Ride to York, Ronald Simmons