Danelaw and the Great North Road

Danelaw arose from a peace deal in the late 9th century between King Alfred and Viking invaders. It placed half of England under Danish law and customs. The area ranged from London to East Anglia, through the East Midlands and up to North Yorkshire. It operated for some 50 years.

Maps illustrating this territory imply that the route of the Great North Road might have been significant since the Danelaw area neatly straddles it. Moreover, the five boroughs of Danelaw included Stamford and Lincoln. York was its principal town.

How much do we really know about Danelaw? To what extent were the differences between the east of the country and the rest of Britain a function of Vikings and Danelaw? What did roads look like at this time and was there anything resembling a north-south arterial route? This article generates far more questions than answers but it is a part of our history where new evidence and techniques are starting to shed important light.

Any thoughts and new material are welcome. I hope this account can evolve as additional information becomes available.

Danelaw – Economic and Political Back Drop

The traditional view of Anglo Saxon England emphasises the impact of a succession of invaders from northern Europe and Scandinavia filling the power vacuum created following the demise of Roman influence in the 5th century. Combined with this was the spread of Christianity and religious influence from southern Europe. Then came more aggressive Danish influence interrupting development of Christianity and extracting “Danegeld” as the price of security. Wealth, trade, technology, science and arts were all in decline. The “Dark Ages”.

We now know that this perspective is oversimplified and flawed. The scant historical and material records point to surprising continuity of agricultural practices, landholding and obligations. Yes, the practice of building in stone left with the Romans but wood was being used in sophisticated ways to create houses, barns, halls, and churches. Wealth accumulated significantly for certain groups, at certain times – not least for many of the new religious establishments with large estates. There were very few towns and most people made their living from agriculture working in largely self sufficient small communities. However, there were leaps forward in agricultural productivity from the 8th century with innovations such as the mould-board plough, free-threshing wheat and crop rotation. Wool became a profitable export commodity. Trade developed around products such as salt from Droitwich and lead from the Pennines. Albeit on a small scale new commercial centres expanded, specialising in production and trade (often with place names ending in”wic” eg Ipswich, Lundenwic, Eoforwic). Water mills, malt houses and other rural industries were developing.

We also see that there were marked regional differences in land holdings, social structure and political oversight which stretch back many centuries and which were not simply the result of specific migrations or invasions. This is particularly true of the area which came to fall under Danelaw. The east of England had since before Roman times had a closer affinity to northern Europe and Scandinavia. The North Sea gave relatively easy linkage to the resources and markets of northern Europe. The river systems reaching the North Sea at the Humber and Wash gave access to large areas of England.

So when the Vikings invaded they were largely imposing themselves upon people with whom they shared ancestry and outlook. Their tactics were “shock and awe” and they had a lust for silver, but when they chose to remain it was not the sudden cultural break which many assume. They arrived as “pagans” but Alfred’s primary condition in establishing Danelaw was that Christianity be respected. Research suggests that the Danelaw area did not have a high level of interaction with the English regions to the south and west, but that may well simply reflect a division that had long existed.

One of the ironies of the Danelaw period is that it helped to consolidate the tribal groups of the east – and made it that much easier for the subsequent unification of England. Alfred’s grandson, Aethelstan, is credited with being the first king of all England following the battle of Brunanburh against a Celtic/Norse army in 937. However, the fragility and complexity of anglo-scandinavian relations was such that by the early 11th century Cnut, a Dane, was King of England, Denmark and Norway.

Danelaw – Organisation

Viking raids were sporadic and opportunistic in the late 8th and early 9th centuries – including the infamous sacking of Lindisfarne in 793. The “Great Heathen Army” under Halfdan Ragnarsson, his brother Ivar the Boneless and warlord Guthrum arrived in 865 starting a more sustained land grab. The Vikings captured York (Eoforwic) in March 867. By 870, the Northmen had also conquered the kingdoms of Northumbria and East Anglia. The reconstruction at top of page is based on excavation of their winter camp at Repton in 873-4. The Danelaw peace settlement agreed in the 880s came after years of inconclusive sparing between the Vikings and King Alfred of Wessex. Guthrum agreed to convert to Christianity, taking the name Aethelstan and settling in East Anglia until his death in 890. Halfdan Ragnarsson assumed control in York.

The Danelaw consisted of 15 shires encompassing the modern counties of York, Nottingham, Derby, Lincoln, Northampton, Cambridge, Huntingdon, Norfolk, Suffolk, Buckingham, Bedford, Hertford, Essex and Middlesex. [Northumbria also came under Danish influence but was ruled separately.]

In the Mercian central area, five fortified towns (“burhs”) served as important bases for political power – Lincoln, Stamford, Derby, Leicester and Nottingham. Each borough was ruled as a Danish Jarldom, with authority to control the lands whilst ultimately answering to York (“Eoforwic or Jorvik”).

The nucleus of York comprised the abbey which coincided with the old Roman fort. A sizeable commercial zone developed close to the river a mile to the south. The population of the town grew from under 2,000 to over 10,000. There is archaeological evidence of ferrous and non-ferrous metal work, textile manufacturing and trade in materials as exotic as amber and silk. There was similar expansion at Lincoln.

At Flixborough on the River Trent, close to where Ermine Street meets the Humber, recent excavation has provided detail on a “productive” Anglo Saxon settlement. It grew by connecting its large hinterland with southern England and northern Europe by river and sea. By the 10th century its connections by land to other emerging towns seem to have been of increasing importance.

Following the death of Halfdan Ragnarsson control in York was taken by Ragnald, a Norwegian Viking from Dublin. He had accepted Alfred’s son, Edward the Elder, as his overlord in 920 although the Danish Kingdom retained a degree of independence from England until 954 when then leader Eric Bloodaxe was killed in an ambush high in the Pennines at Stainmore.

The Anglo Saxon Chronicles are one of the few sources with respect to the battles and politics of this time. There’s even less to guide our understanding of where and how people travelled.

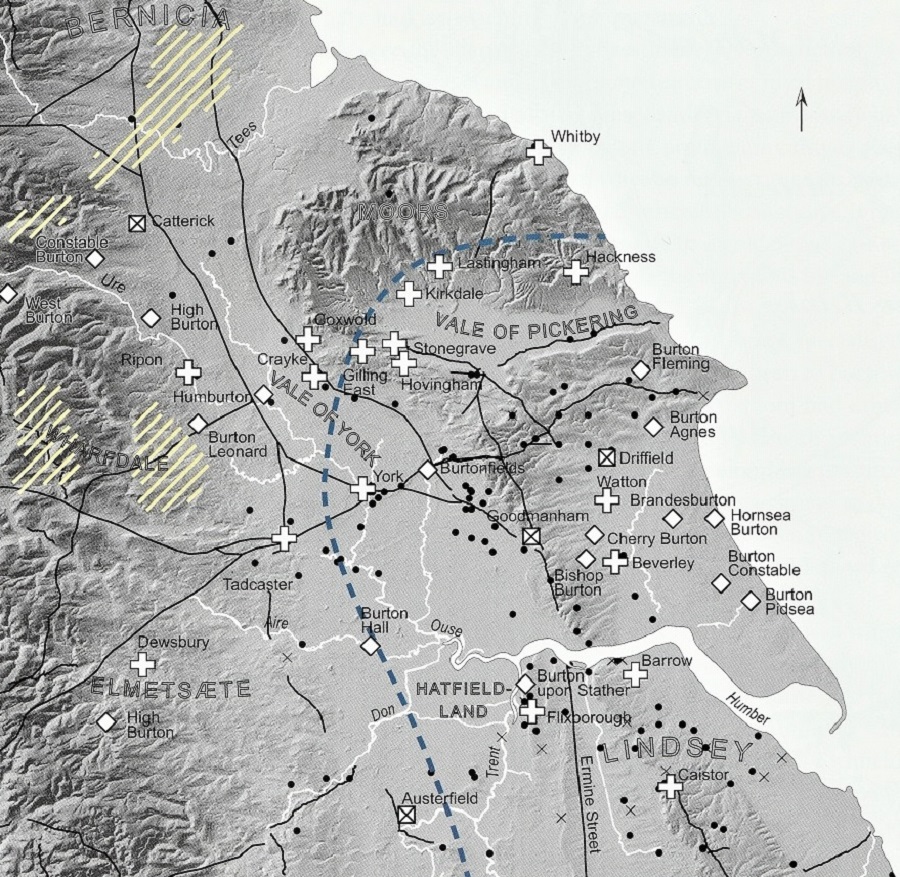

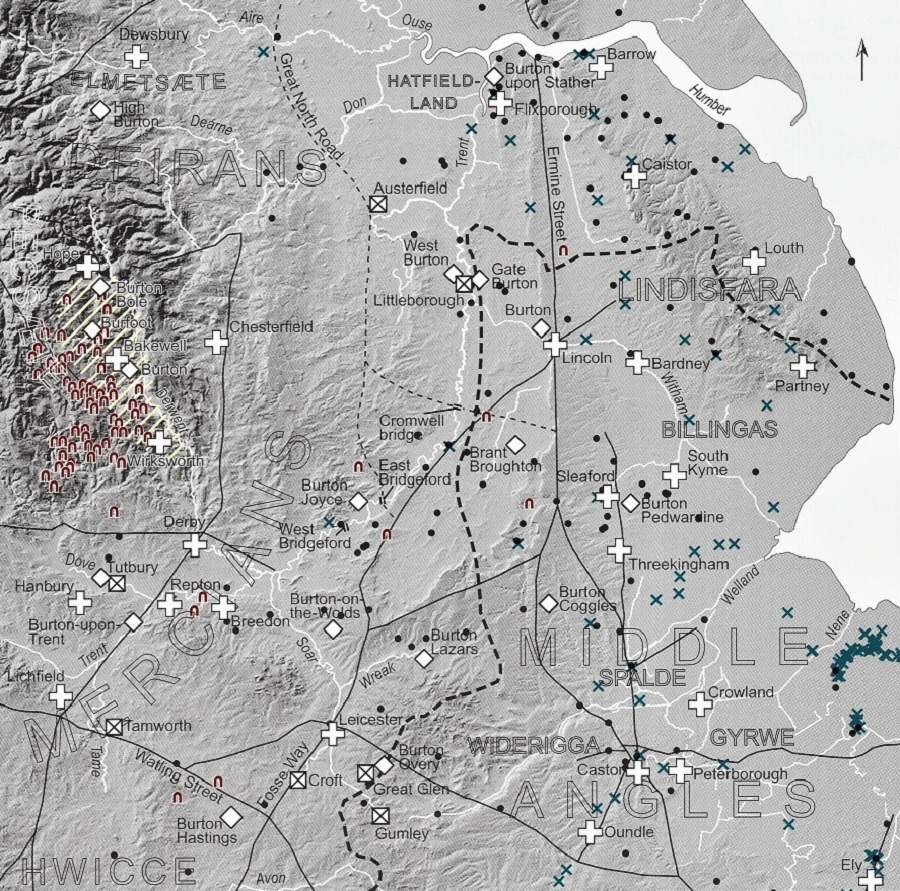

Eighth Century Deira and Mercia. Credit – J Blair

Late Anglo Saxon – Roads and Communication

The amount of communication was clearly massively less than we think of today. Most food and other goods were still produced locally. The total population of England was less than 2m. Towns were still mostly for administration and control rather than trade. Political and legal power was heavily devolved.

There was a legacy of Roman roads in the landscape and these would have been quite adequate for most purposes. Often trips would be on foot or by horse. Hand and animal drawn carts would mainly be only for short distances.

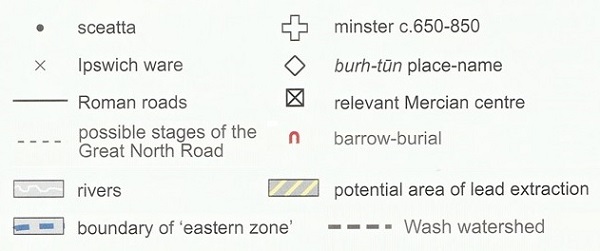

Bridges would be the weak point. Even the Romans built bridges mainly of wood so inevitably few would have survived more than a 100 years. However, by the 8th century there are signs that leaders and the church were once again starting to tackle bridge building and maintenance. In a decree of 749, King Aethelbald of Mercia imposed an obligation for monastic manpower to contribute to bridge building. It is likely that his primary concern would have been those crossing the major river in his own kingdom, the Trent. There are indeed remains of a long wooden bridge at Cromwell (Ogilby mile post 124) north of Newark which has been dated to circa 740-50 by dendrochronology. John Blair observes that:

“The local topography suggests that the Cromwell bridge connected westwards with the Great North Road, or an earlier version of it, and eastwards with routes to Lincoln and the east, taking advantage of a minor Roman road”

During earlier Anglo Saxon times one of the primary roads was Fosse Way between Lincoln and the south-west, running through much of Mercia. It is likely that Danelaw would have placed more emphasis on the north-south route connecting key towns such as York, Lincoln and Stamford with London and East Anglia. Longer trips and heavier loads would be by river and sea. Rivers were less disrupted by weirs and mills and shallow bottomed boats could reach into much of the Danelaw region. Sea-going boats would be used not only for trips to and from Scandinavia but also as the simplest means of travel and transport the length of the east coast.

Other clues as to the state of roads by the 10th and 11th centuries come from the routes taken by marauding factional armies as they attacked and defended territories. Not least is the remarkable speed with which King Harold was able to travel from London to York in 1066 to head off the attack by Hardrada and Tostig prior to William’s arrival in Kent.

More Information

John Blair, Building Anglo-Saxon England

Chris Loveluck, Rural Settlement, Lifestyles and Social Change – Anglo-Saxon Flixborough