Eleanor Crosses and the Great North Road

Queen Eleanor, the beloved wife of Edward I, died at Harby near the Nottinghamshire-Lincolnshire border in November 1290. After three days of mourning, she was taken to St Katherine’s Priory at Lincoln where her body was embalmed. The cortège set off from Lincoln on Monday 4th December heading to Westminster Abbey in London. Initially, the route followed the ancient Ermine Street, though from Stamford the royal party travelled west to the safer winter crossing point of the Great Ouse at Stony Stratford.

Eleanor’s coffin was carried by horse drawn cart; Edward accompanied on foot as a mark of respect. It is believed that the royal party would have comprised up to a hundred including nobles, armed knights, religious officials, courtiers, and servants. The convoy with perhaps a dozen carts travelled 10 to 25 miles each day typically resting in abbeys and monasteries.

In January 1291 Edward requested the presence of Richard of Crundale and other royal master masons to plan the building of crosses to be erected at the overnight resting places of Eleanor’s coffin. Each cross had a flight of steps and was built in three stages, the first stage consisting of 3, 6 or 8 sides bearing carved heraldic shields of England, Castille, Leon and Ponthieu. The second stage was a platform upon which stood as many statues of Eleanor as there were sides. A tabernacle encased each statue to give the impression of a shrine. The third stage continued the column and was surmounted by a wooden cross. The style of the crosses reflected the architectural transition at the end of the 13th Century from “Early English” to “Decorated” Gothic.

Their total height was 49 feet and this is suggested to have represented Eleanor’s age when she died. At a time when few manmade structures stood higher than a one or two storey cottage, the Eleanor Crosses would have made a striking impact on the landscape.

The surviving Eleanor Cross at Geddington near Corby (Image credit: Rex Gibson)

For centuries, the crosses formed prominent landmarks along the Great North Road. Though only three of the original crosses remain they have provided a long-lasting memorial to a feisty queen. They have found their way into popular culture; they are remembered in place names: and they have been imitated repeatedly.

In the 19th century architect George Gilbert Scott helped popularise the Eleanor crosses and drew heavily on them when designing a new gothic cross for Oxford and indeed later, the Albert Memorial of 1872.

All aspects of Eleanor’s passing were on an elaborate scale, planned by a grieving monarch who sought salvation for her soul and respect from his subjects. Her body was buried at the newly built Westminster Abbey but there were separate internments for her viscera in the Angel Choir of Lincoln Abbey, and for her heart at Black Friars, London. The leading goldsmith, William Torel created the most magnificent effigies of Eleanor for her Westminster and Lincoln tombs. The life-size gilded bronze castings were unique at this time. Edward endowed Westminster Abbey with 7 of Eleanor’s properties to fund a lavish memorial service each year. A chantry chapel was added to the church at Harby.

This single aisled rectangular building retaining elements of the original church and chantry chapel was replaced in the 1870s by the current Harby All Saints’ parish church.

About Queen Eleanor of Castile

The remarkable wife of King Edward I, Eleanor was a dynamic and forceful personality who, with her husband, helped shape Britain in the second half of the 13th century.

Eleanor was daughter of Ferdinand III, King of Castille, whose family had been instrumental in bringing the power of the Almohads to an end in the Iberian peninsula, creating in Castille the platform for Spanish union.

Edward was eldest son of Henry III, who ruled (not very effectively) a kingdom which spanned both England and the Plantagenet dominions of western France. His mother was Eleanor of Provence (she in fact originated from Saxony). Both Edward and Eleanor shared another famous ancestor, Eleanor of Aquitaine, who had been a powerful Queen of France then England in the 12th century.

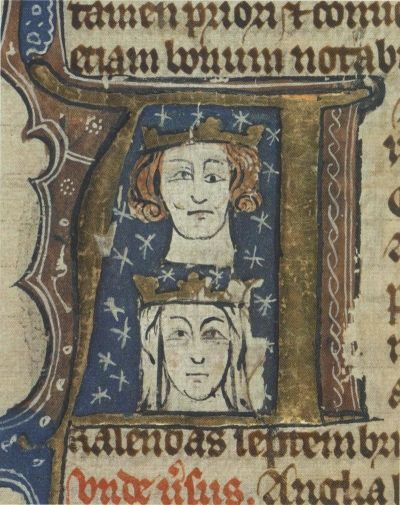

Image of Edward and Eleanor from a 14th century manuscript

Eleanor first met Edward at the time of their wedding in Burgos in 1254 when she was just 12 and he was 15. They started married life as they would often continue it, travelling and networking, with a journey to assert his authority over Gascony. Eleanor arrived in England a in late 1255, greeted with a ceremonial parade and feasting, followed by a tour around their future kingdom.

Eleanor was intelligent, well-educated and enjoyed the comforts of court life. She is credited with introducing tapestries and carpets to England and her preferences regarding architecture and gardens drew on her Spanish background. Edward was tall, strong, charismatic and brought up on Arthurian legends of chivalry and knighthood. He greatly enjoyed tournaments and one is recorded at Blyth (near Bawtry, south of Doncaster) in 1256. It is likely Eleanor was present and then travelled on to Scotland to meet Edward’s sister Margaret and her husband Alexander of Scotland. Whilst in their 20s both Edward and Eleanor were imprisoned during the second Barons’ War; Edward escaped and rallied support against the rising culminating in the defeat of the rebels under De Montfort.

The initial dower lands provided to Eleanor upon her marriage to provide a level of financial independence included the towns of Stamford and Grantham. She built on this foundation throughout her life, personally involved in many of the investment and management decisions, until by her death the estate was providing an income of £2,500 per annum. Her properties were widely spread but included concentrations in south Lincolnshire and Northamptonshire. Some were conveniently located to facilitate her passion for hunting.

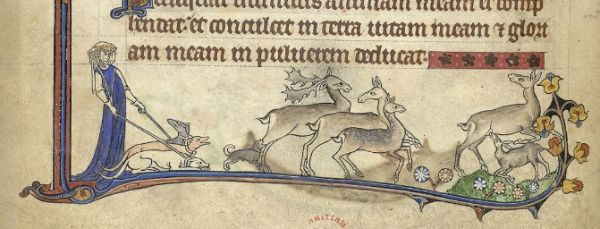

The psalter commissioned by Eleanor for her son Alphonso includes this image of a hunting lady with dogs (Image Credit – British Library)

Edward’s father died whilst he and Eleanor were returning from crusade in late 1272. The couple travelled with their latest son, Alphonso (born at Dacre), and enjoyed fine hospitality as they made their way slowly home, not arriving until August 1274. They were crowned a month later in the impressive Westminster Abbey, recently completed by Edward’s father, with its shrine to Edward the Confessor underlining the primacy of the English royalty. A busy and eventful reign followed. Eleanor gave birth to 15 children (many of whom died early). Edward and Eleanor were forever travelling, holding court across the country, visiting newly founded abbeys, networking with influential nobles and supervising the royal estate. Welsh uprisings were suppressed in the 1270s and 1280s, and the great castles of North Wales established. It was at Caernarvon in 1284 that Eleanor’s last child, the future Edward II was born. Later that year the couple were in Lincoln for the consecration of the shrine of St Hugh. Leeds Castle in Kent was acquired by the couple and was upgraded under the influence of Eleanor with suites of private rooms, a Castilian style bathroom, new gardens and a lake. Eleanor became Countess of Ponthieu in 1279 (a small enclave in northwest France) which she soon visited and where she continued her habit of acquiring property.

The late 1280s were spent in Gascony, then a return home for the strategic weddings of two of their daughters. In 1290 the royal couple meandered north, visiting Eleanor’s midland properties and then attending a parliament in Clipstone, a hunting lodge in Sherwood Forest. Eleanor fell ill, to the point that her younger children were summoned from London. Plans to travel to Scotland were abandoned and instead the royal party headed the 20 miles towards Lincoln. Even this modest journey proved impossible and 2 weeks later Eleanor died aged 49 in a modest manor house at Harby.

A statue of Edward and Eleanor on the south side of Lincoln Cathedral. (Image Credit – Rex Gibson)

Sara Cockerill’s detailed account of Eleanor’s life gives the impression of a closely aligned royal couple managing a multinational corporation through good times and bad, dealing with strategic and operational issues, publicity, finance and succession. They understand power base politics and demonstrate a work hard, play hard, sometimes brutal, culture. Her conclusion is:

“Close examination of the record shows again and again the traces of her subtle touch in directing his political and even his military endeavours.

She was a highly influential adviser to Edward throughout their marriage. She helped to develop in him the abilities which he had and she assisted him with much relevant knowledge as his career progressed. Indeed, one cannot help but wonder whether, without Eleanor, Edward would have become such an outstanding king that the accolade of greatness is often bestowed on him.”

This thoughtful, well researched favourable appraisal of Eleanor is not how she has been portrayed over the centuries. During her lifetime there was plenty of sniping as she accumulated her property empire. Her Spanish, French and Catholic origins were perhaps inevitably held against her in the centuries following her death. More recently she found herself in the shadow of Edward I with people knowing her from the famous crosses but not appreciating the significance of her personal contribution to a new era for the English monarchy.

Route of Queen Eleanor’s Funeral Procession

The interactive map below shows the location of the Eleanor Crosses and the approximate route of the procession. [If you can point to evidence which improves the accuracy of this route please contact me.]

The stops after Lincoln were Grantham and Stamford (in Lincolnshire), Geddington (Northamptonshire), Hardingstone and Stony Stratford (Buckinghamshire), Woburn Abbey (Bedfordshire), and then Dunstable and St Albans (in Hertfordshire). Edward left St Albans to travel to London and the funeral party journeyed to Waltham Abbey (Essex). Entering London through Bishopsgate on Thursday, 14 December, the funeral party stopped at Holy Trinity Priory in the east of the walled city. The following day they travelled westwards along Cheapside, halting at Grey Friars and St Paul’s Cathedral. The next day was the final day of the procession and, after a mass at Black Friars, the coffin arrived at Westminster Abbey on Saturday, 16 December, with the funeral taking place the following day.

The route chosen from Lincoln to London might seem somewhat indirect but there were good reasons. Most importantly, at this time of year it could be problematic to cross the low-lying valleys of the Nene and Great Ouse; many north-south travellers of this era preferred the higher, more westerly roads, crossing the Ouse on the line of the Roman Watling Street. The route through Rockingham Forest between Stamford and Northampton took in estates owned by Eleanor and regularly visited by the royal couple. Prominent religious houses where prayers could be offered were selected for overnight stops. And the route also gave plenty of opportunity for thousands of people to witness the unique funeral procession.

Location of The Eleanor Crosses

Each memorial cross was sited in a prominent position on the funeral journey, near Eleanor’s resting place for that night of the procession. The choice was usually for a significant crossroads, junction or high street where Eleanor’s body had directly passed by, sometimes in the town or village, sometimes outside.

Lincoln

Grantham

Stamford

Geddington (surviving)

Northampton – Hardingstone (surviving)

Stony Stratford

Woburn

Dunstable

St Albans

Waltham (surviving)

London – Cheapside

London – Charing

All 12 memorial crosses and the three tombs were finished within 4 years of Queen Eleanor’s death.

There was a long history of crosses commemorating notable religious figures, events or boundaries dating back to the earliest days of Christianity. Many of the earlier crosses were very modest; the Eleanor Crosses rather less so – building on the precedent of the memorials created in the 1270s for King Louis IX of France, her uncle, who had died on the crusade in which Edward and Eleanor had participated.

The sections below explore in more detail a few of the Eleanor Crosses in places featured on the Great North Road website.

Lincoln

The cross at Lincoln was placed outside the walls at the gates of St Katherine’s Priory at Swine Green at the foot of Cross-o-cliff Hill. This was close to the junction of Fosse Way and Ermine Street. The cross was built by mason Richard of Stow. Records show that it was repaired by the city authorities in 1624, though it was destroyed during the Civil War about 20 years later. A fragment of a statue of Eleanor was rescued from use as a footbridge in the 19th century and can now be seen in the grounds of Lincoln Castle.

Remnant of the Lincoln Cross (Image Credit – Rex Gibson)

Grantham

Grantham Cross stood on what is now St Peter’s Hill on the High Street. It was destroyed during the Civil War and no traces remain.

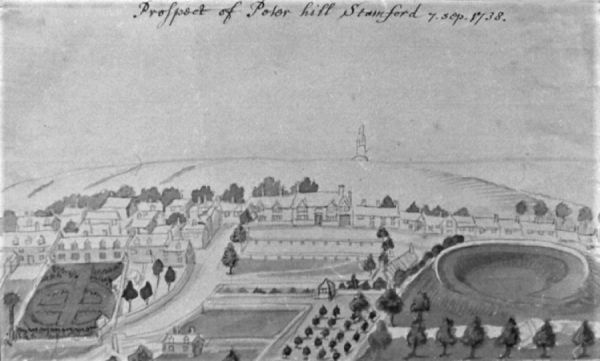

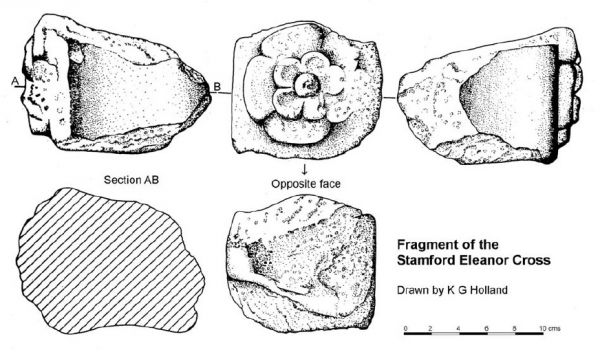

Stamford

For 350 years The Queen’s Cross was a prominent landmark close to the Great North Road just north of Stamford. Until destroyed by Cromwellian forces it stood to the southwest of the road on higher ground then known then as Anemone Hill between Stamford and Great Casterton. The date of its demise suggests that the image above involved artistic licence.

Captain Richard Symonds of the Royalist army visited Stamford on his way from Newark to Huntingdon on 22 August 1645. He wrote:

“In the hill before ye into the towne stands a lofty large cross, built by Edward I in memory of Eleanor whose corps rested there coming from the north. Upon the top of this cross these three shields shields are often carved: England; three bends sinister; a bordure (Ponthieu); Quarterly Castile and Leon”

A year later in The Survey and Antiquitie of the Towne of Stamford, Richard Butcher writes:

Not farre from hence upon the Northe side of the Town unto York highway and about twelvescore from the Town gate, which is called Clement-gate, stands an ancient Crosse of free stone of a very curious fabrick, having many ancient scutchions of Armes insculped in the stone, about it; as the Armes of Castile and Leon, quartered, being the paternall coat of the King of Spain, and divers other Hatchments belonging to that Crown, which envious time hath so defaced, that only the ruins appeare to my eye, and therefore not to be described by my pen. This Crosse is called the Queens Crosse, and was erected in this place by King Edward the first about Anno Dom. 1293.

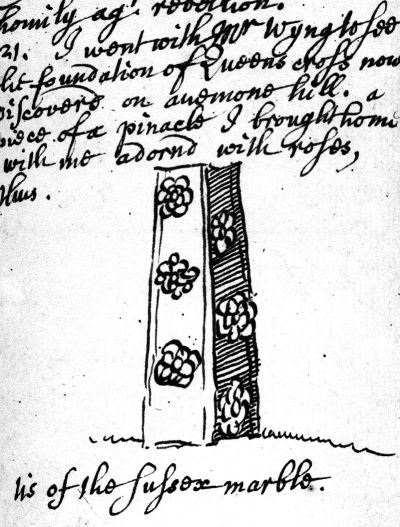

The base of the Stamford cross was excavated by local antiquarian, William Stukeley, vicar of All Saints in 1745. He had long suspected that a tumulus on the Casterton Road marked the base of the cross, and when the turnpike surveyor began digging in the area for road stone, he was able to excavate the foundations. His reports describe the base as having 6 or 8 sides.

Stukeley’s sketch suggests a substantial pyramidal section adorned with roses (Edward’s personal emblem) was seen by him before being removed to his garden. A marble rose was rediscovered in the 1990s and prompted the 2009 homage to the cross by Wolfgang Buttress. It stands in Sheepmarket in Stamford.

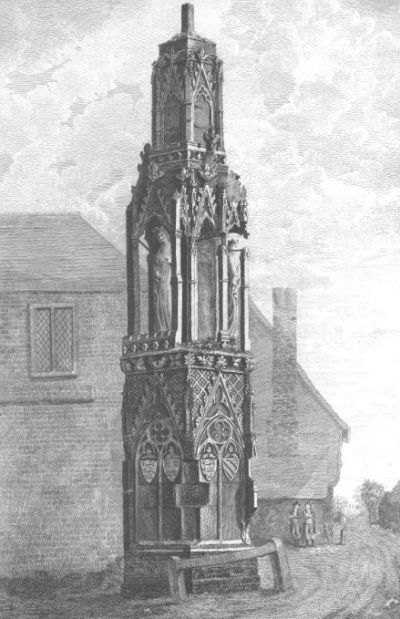

Waltham Cross

The cross built a mile west of Eleanor’s overnight resting place at Waltham Abbey would later give the area around it its name. The much restored and modified monument now stands incongruously in the centre of Waltham Cross.

[Image Credit – Hertfordshire CCTV Partnership]

These sketches of the figures on the Eleanor Cross at Waltham show why they are often considered to be the finest; the statues visible today are replicas, the originals were removed to the Victoria & Albert Museum

As early as 1721 the Society of Antiquaries had expressed concern at the damage being caused to the monument by rapidly increasing road traffic. Antiquarian and future Society president, William Stukeley, sketched the cross, and oak bollards were set in the road to prevent vehicles driving too close.

The cross was the work of masons Roger of Crundale and Nicholas Dymenge. It was originally a five-stage cross, hexagonal in plan.

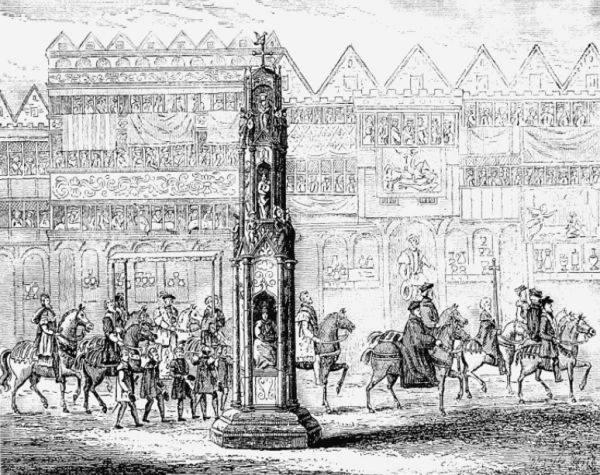

London – Cheapside

Procession of Edward VI to his coronation in 1547, James Basire (18th century)

The West Cheap or Cheapside cross was prominently located outside St Peter’s, opposite the entrance to Wood Street. It cost 3 times as much as the less lavish Lincoln cross; it featured regularly in ceremonial occasions, including the celebration of Henry V’s victory at Agincourt in 1415. In fact the cross was re-gilded for the occasion. Maintenance and reconstruction continued over the centuries.

A 1638 image by La Serre depicting the Procession of Mary de Medici

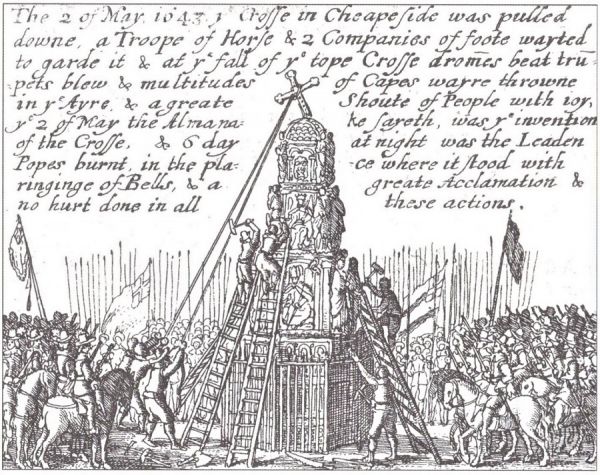

During the Civil War the Cheapside Cross became the focus of fierce dispute. The Parliamentarians saw it as a representation of all things “Papistry” and the monarchy. In 1643 a warrant was issued by Parliament for the demolition of the cross. On 2nd May Sir Robert Harlow with a troop of horse and two companies of foot toppled the idolatrous Cheapside cross – seemingly watched by a large and jubilant crowd.

The demolition of the Cheapside Cross, Besant, 1903

Fragments of the Cheapside Cross showing the arms of England and Castille are held by the Museum of London.

London – Charing Cross

For centuries, this Eleanor Cross became the reference point for measing distances to London. Even today, Google Maps locate London just a few metres away.

The original Charing Cross suffered the same fate as that at Cheapside, by order of the anti-monarchist Parliament. It was replaced in 1675 by an equestrian statue of King Charles I, fifteen years after the monarchy was restored.

King Charles I in the shadow of Nelson’s Column facing toward the Houses of Parliament. The oldest bronze statue in London. [Image Credit – Tracy Jenkins, Art UK, CC BY-NC 4.0 DEED]

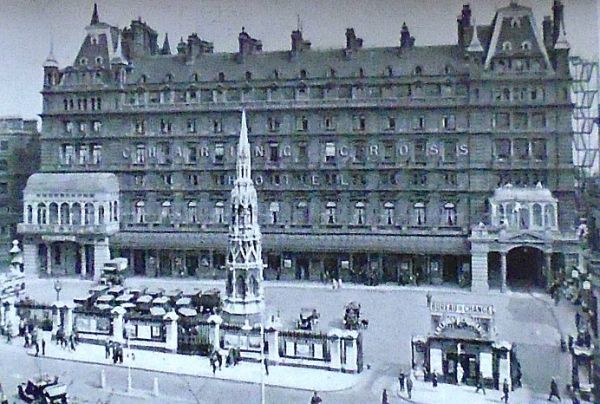

In the 19th century a grand reproduction was carved by Thomas Earp: it was designed by Edward Middleton Barry who was also the architect of the Charing Cross hotel in front of which it stands.

The replica “Charing Cross” in front of Charing Cross station

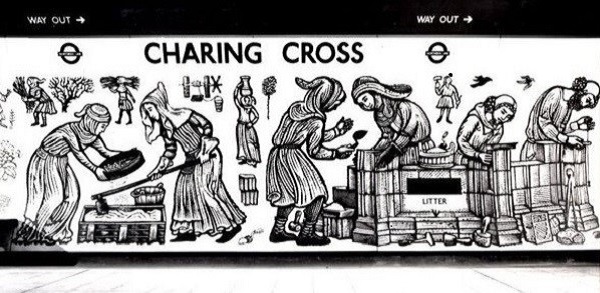

Construction of the original cross is remembered by the murals along the platform of the Northern Line

More Information about the Eleanor Crosses

Eleanor of Castille, Sara Cockerill, 2014

The Eleanor Crosses, Decca Warrington, 2018

Top of page Image Credit: Westminster Abbey