Hadrian’s Wall and the Great North Road

Hadrian’s Wall embodies one of the key reasons for the existence of the Roman Roads north through Britain which were the precursors to our Great North Road. Lying at the northern boundary of a vast empire ruled from a distance of 1,500 miles it was essential to establish efficient communications and supply lines.

About Hadrian’s Wall

Four decades after the invasion of southern England by Claudius in AD43, the Romans marched north to conquer the native Caledonians. The Romans are said to have won a bloody victory at the Battle of Mons Graupius cAD84. The Gask frontier comprising wooden and turf forts was established in Perthshire.

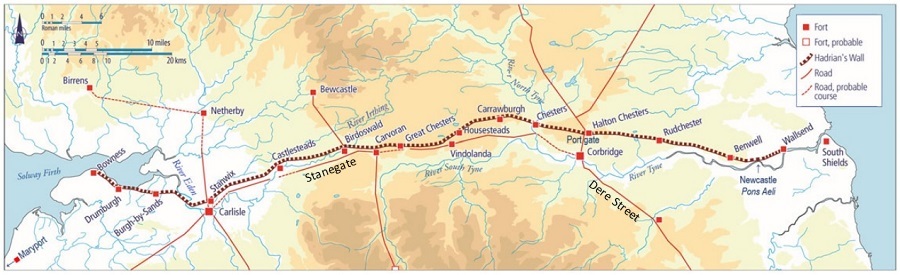

Whilst Roman influence persisted in southern Scotland, military control waned as soldiers were withdrawn to fight on more critical fronts such as the Danube. On becoming Roman Emperor in AD117, Hadrian set about making the Empire more secure, separating Roman and Barbarian territories. The coast to coast wall across northern England was perhaps the most dramatic example. The 73 mile barrier from the Solway Firth in the West to Wallsend in the East was a massive construction and logistical project. Hadrian came to inspect progress in AD122.

Prior to the wall being built a series of forts had been established across the width of the country along the line of a major road – Stanegate. The wall was established immediately to the north of this. Stanegate intersected the north-south Dere Street at Corbridge and the gate through the wall at this point is known as Portgate.

Image Credit – After David Breeze

It is thought to have taken three legions of 5,000 infantrymen around six years to complete the wall. The finished structure had 80 “milecastles”, numerous observation towers and 17 larger forts. The photo above includes milecastle 39 near to Vindolanda. Between the milecastles were two towers so that observation points were created at every third of a mile. Constructed mainly from stone and in parts initially from turf, the wall was up to six metres high and three metres deep. Along the south face of the wall, if there was no river or crag to provide extra defence, a deep ditch was dug.

Hadrian’s Wall itself was abandoned only 25 years after it was built and a new turf and timber wall was constructed further north between Clyde and Forth – the Antonine Wall. After another 25 years Hadrian’s Wall was re-established as the frontier line. A major war took place shortly after AD180, when:

‘the tribes crossed the wall which divided them from the Roman forts and killed a general and the troops he had with him’.

In the early third century the African Emperor Severus led a vast army north of Hadrian’s Wall. He died in York and his sons made a peace with local tribes which lasted for a hundred years. Many of the forts along Hadrian’s Wall continued to be occupied into the 5th and 6th centuries, long after Roman Imperial rule in Britain had ended.

The wall was much robbed of stone over the subsequent centuries, not least by General Wade in the 18th century when rushing to quell the Jacobite insurrection. However, the Roman remains along the length of Hadrian’s Wall continue to offer great insights to archaeologists looking to piece together the lives of those who lived and worked there.

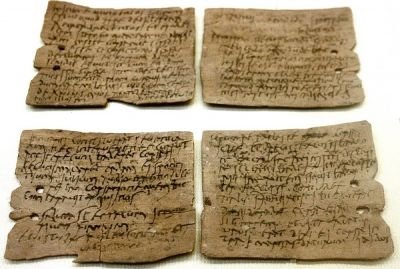

The Vindolanda tablets are the oldest surviving handwritten documents in Britain. The postcard-length messages often concern trivial social and business activities. Perhaps unsurprisingly given its importance in servicing Hadrian’s Wall, places along the Great North Road feature amongst the towns mentioned on the tablets: