Lindisfarne and the Great North Road

The Holy Island of Lindisfarne lies 4 miles from the Great North Road between Berwick and Newcastle. The Northumberland coast is magnificent, and Lindisfarne is one of its most magical features.

As well as being a striking tidal island, travellers along the Great North Road have been absorbed for more than a millennium by its prominent role in early British Christianity and its infamous reputation as the scene of a gruesome Viking massacre.

To avoid the loss of one of the most holy of relics, the remains of Saint Cuthbert were taken from Lindisfarne by monks – ending up more than 100 years later at Durham, 60 miles to the south.

The golden sands between Berwick and Lindisfarne have enticed those seeking a direct and less hilly route than the Great North Road. Harper relates the story of the postboy carrying the mails from Edinburgh on 20th November 1725. Neither he nor his mailbags were heard of again after leaving Berwick, and it was concluded he was lost on the quicksands in a sea fog.

If you are planning to visit, the first essential thing to do is to check the tide table. Lindisfarne is connected to the mainland by a one-mile causeway for 6 to 9 hours twice per day. The road from the A1 is via the small village of Beal.

Image credit – Belvue Guesthouse Holy Island, 2017

Sir Walter Scott, the Scottish historical novelist, playwright and poet described Lindisfarne in poetic terms:

The tide did now its flood-mark gain,

And girdled in the saint’s domain:

For, with the flow and ebb, its style

Varies from continent to isle;

Dry-shod, o’er sands, twice every day,

The pilgrims to the shrine find way;

Twice every day, the waves efface

Of staves and sandalled feet the trace.

As to the port the galley flew,

Higher and higher rose to view

The castle with its battled walls,

The ancient monastery’s halls,

A solemn, huge, and dark red pile,

Placed on the margin of the isle.

About Lindisfarne

Mont-Saint-Michel, Iona, St Michael’s Mount, Capri, Lindisfarne. On the edge, exposed to the elements and offering degrees of isolation. There is something evocative in small close to shore islands which defines them as special places and draws people to them. They can also be very useful when it comes to defence.

Drawn and engraved by William Woolnoth, c1830

Lindisfarne has seen long term settlement since the Mesolthic but it was during the early medieval period that it came to make its mark on British history.

Hadrian’s Wall and control of the Scottish border lands was of great importance to Roman imperial rulers. When the military presence collapsed in the early 5th century, smaller kingdoms emerged. In the 6th century Lindisfarne (referred to then as The Isle of the Winds) was in the hands of King Uriens of Rheged and there was a small fort on the island. In about AD 550, a 3-day battle focused on Lindisfarne saw Uriens betrayed by an ally – handing victory to the Anglo-Saxon King Ida who had already taken over Bamburgh, the capital of Bernicia. Ida’s great grandson, Oswald came to power in 634. By this time the Northumbrian kingdom dominated Britain, consisting of two parts: Deira, centred on the old Roman city of York, and Bernicia further north. Oswald’s accession focused Northumbrian power in Bernicia, around the royal palaces at Yeavering, Mælmin (Milfield) and Bamburgh.

Early in the 7th century Christianity was making intermittent inroads into royal circles, some taking the Roman path, some the Irish, and others sticking to tradition. Oswald had been exiled with his mother to the Scottish Kingdom of Dal Riada at the age of 12; he was sent to the Christian island of Iona for his education. He returned in 634 upon the death of his pagan older brother, Eanfrith.

Oswald brought St Aidan, an Irish monk from Iona, to re-establish Christianity in Northumbria. A monastery was set up on Lindisfarne with Aidan the first bishop. Other monasteries followed at Hartlepool, York and Lastingham. Oswald was convinced that his faith was key to his military success, but eventually his luck ran out and he was killed in 642 in a battle with the pagan Mercians under Penda. His bones were moved to Bardney Abbey near Lincoln in Lindsey where he was venerated as a saint.

The origin of the name Lindisfarne may well originate from Lincolnshire. Lindisfaran is believed by some to be the Anglo-Saxon group name of the people who migrated (faran) to the territory of Lindis (loosely, the northern part of today’s Lincolnshire). There is plausible evidence that a group of Anglo-Saxon settlers may have sailed north to establish a coastal settlement in the area of Lindisfarne and Bamburgh in the 6th century.

Northern Britain in the early Middle Ages (English Heritage)

Cuthbert came to Lindisfarne in the 7th century, where his reputed gift of healing and miracle working brought long and far-reaching fame for the island. Born near Lauderdale (upper Tweed valley) Cuthbert helped found a monastery at Ripon where he became Prior in 664. He participated in the famous synod of Whitby in 674 seemingly accepting the integration of various aspects of Roman and Celtic Christianity. He retreated to live the life of a hermit but was appointed a Bishop in 684; he would only accept this role if it was to be at Lindisfarne. He died two years later.

Medieval wall painting of St. Cuthbert from Durham Cathedral’s Galilee Chapel

In 698 the monastery’s monks exhumed his body so that it could be reburied. Bede wrote:

“When they opened the grave they found the body whole and incorrupt … the brothers were awestruck, and hastened to inform the bishop of their discovery, [the brothers then] clothed the body in fresh garments, they laid it in a new coffin which they placed on the floor of the sanctuary”

The monks were now even more convinced that Cuthbert was a saint and pilgrims flocked to Lindisfarne.

For the next century the monastery at Lindisfarne remained a centre for Christianity in Britain. One of its most notable achievements was the early 8th century illuminated manuscript known as the Lindisfarne Gospels. The unique style of the beautiful illustrations combines Anglo-Saxon, Celtic and Mediterranean elements, using inks sourced from across the western world. In the late 10th century an Anglo-Saxon text was added making them the earliest surviving Old English version of the Gospels. The Lindisfarne Gospels now reside in the British Library in London.

Reconstruction of the 9th century Norwegian Viking ship – Gokstad (Image Credit – Tarje Pladsen)

The fame and influence of Lindisfarne spread far and wide. Its wealth became well known. It started to be the target of unwanted visitors with a first Viking incursion in 787 reported by Bede. In 793 the island became the target of a more serious raid. It is sometimes billed as the start of the Viking invasion of England. Many of the historical records were written long after the event are likely to be exaggerated but there is little doubt that it was a vicious and bloody massacre. There might have been a religious or strategic objective, but it is quite possible that a bounty of silver was the only justification needed by the Scandinavians at this time.

The only contemporary account we have was written by a much-respected monk, Alcuin, in the form of a poem and a series of letters to the King of Northumbria and the Bishop of Lindisfarne. The letters are believed to be responses to letters written to him whilst he was in Germany. Alcuin was Northumbrian by birth but had been called to the Carolingian Court at Aachen by Charlemagne. As well as a theologian, Alcuin was a mathematician, historian and poet. His poem “De clade Lindisfarnensis monasterii” (On the destruction of the monastery of Lindisfarne) places the Lindisfarne attack in the same context as other collapses of civilisation such as Rome and Babylon. His letters request that leaders consider what actions may have brought about such divine retribution.

“Lo, it is nearly 350 years that we and our fathers have inhabited this most lovely land, and never before has such terror appeared in Britain as we have now suffered from a pagan race, nor was it thought that such an inroad from the sea could be made. Behold the church of St Cuthbert spattered with the blood of the priests of God, despoiled of all its ornaments; a place more venerable than all in Britain is given as a prey to pagan peoples…”.

“Consider carefully, brothers, and examine diligently, lest perchance this unaccustomed and unheard-of evil was merited by some unheard-of evil practice… Consider the dress, the way of wearing the hair, the luxurious habits of the princes and people.”

Letter from Alcuin to Ethelred, King of Northumbria.

The 9th-century grave marker found at Lindisfarne, known as the Viking Raider Stone (Image Credit – English Heritage)

Viking raids on Lindisfarne’s wealthy coastal monastery continued throughout the following century and in 875 the monks of Lindisfarne finally fled with the body of Cuthbert. For many years the monks were itinerant. Then after settling for a hundred years in the old Roman fort at Chester-le-Street they moved on to Durham in 995 where St Cuthbert’s body lies to this day in Durham Cathedral.

The monastic community continued at Lindisfarne through the 10th century and indeed in 1069 the Durham monks returned briefly with St Cuthbert’s relics to escape the “harrying of the north” by William the Conqueror. Lindisfarne became a daughter house of the Benedictine monastery at Durham in 1093.

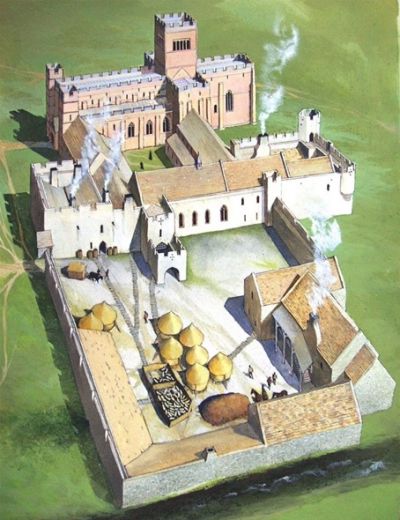

The priory church visible today was built by about 1150 and is probably on the same site as its Anglo-Saxon predecessor; its architecture echoes that of the Romanesque cathedral at Durham. The church contained a cenotaph (an empty tomb) marking the spot where Cuthbert’s body had been buried and this remained a sacred spot which drew many pilgrims.

Battlements and cross-shaped arrowslits were added in the 14th century when the whole priory was fortified in response to the outbreak of war with the Scots.

Reconstruction showing how the priory buildings may have looked in about 1500 (Image Credit – David Simon, Historic England)

The Benedictine priory continued until its suppression in 1536 after which the buildings surrounding the church were used as a naval storehouse. In 1542–5 three earth-and-timber defences were built around the harbour to the east of the priory.

By the 18th century the ruinous but recognisable remains had become a popular tourist attraction for antiquarians, artists and travellers along the Great North Road. Drawings and descriptions show that until about 1780 the church survived virtually intact but soon after the central tower and south aisle had collapsed.

Holy Island Monastery, Lindisfarne, 1785

Lindisfarne Priory today. Just offshore is St Cuthbert’s Isle (Image Credit – English Heritage)

The priory was located on the low lying “tail” of the island. The building perched on top of its highpoint is Lindisfarne Castle, built in the mid-16th century as a defence against border raids by the Scots. Its military importance was diminished after the unification of England and Scotland under James I though it continued to be occupied by garrisons of soldiers on detachment from the larger force based at nearby Berwick.

During the Jacobite Rising of 1715 a small group of local sympathisers overpowered the three soldiers left in charge of the castle. They claimed the castle as a landing site for the Jacobite group led by Northumberland MP, Thomas Forster. When 100 men arrived from Berwick to retake the castle, the rebels were only able to hold out for one day. Fleeing, they were captured at the tollbooth at Berwick.

The remnants of the castle were converted into a romantic Edwardian retreat by Edward Hudson, founder and proprietor of the Country Life magazine. Architect, Edwin Lutyens emphasised the buildings organic relationship with the rock from which it emerges. Inside, he created a labyrinth of reception rooms and bedrooms, reached by stone ramps, twisting passageways and narrow stairs.

The castle, garden and nearby lime kilns are cared for by the National Trust.

Lindisfarne Priory is an English Heritage property.

More Information about Lindisfarne

Top of page Image Credit: Man of Yorkshire, flickr.com