King James I and the Great North Road

Sting was not thinking of James I when he wrote this but travelling the Great North Road to try a new gig in London seems appropriate.

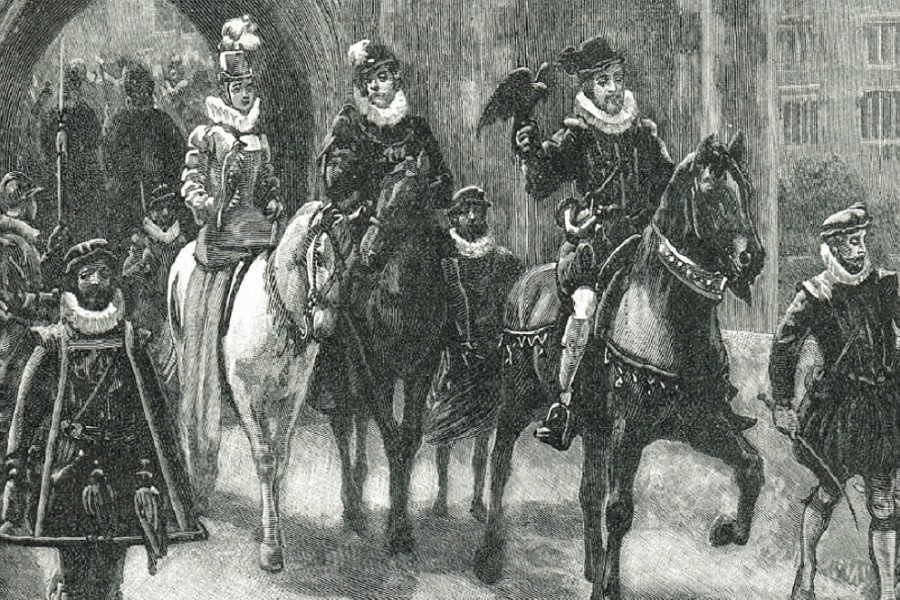

A meandering but triumphant journey south along the Great North Road marked the start of the reign of King James I in 1603. It was his first visit to England and he was impressed by its countryside, prosperity, and fine houses. He was given a warm welcome. He established many connections which remained important to him. A number of places where he stayed were re-visited many times during his reign.

With no direct heir, the succession to the English throne after Elizabeth had been uncertain. She was reluctant to accept the recommendation of James by her secretary, Robert Cecil. It was only on her deathbed in March 1603 that she finally gave way.

Sir Robert Carey was dispatched to Edinburgh on 24th March on the day of Elizabeth’s death. He carried a sapphire ring that was the prearranged proof of the queen’s demise. His first overnight stop was at Doncaster, his second at Widdrington in Northumberland (his own home). He suffered a fall on the third day but arrived in Edinburgh that evening ‘be-blooded and bruised’ and was able to greet James as King of England, Scotland and Ireland.

There followed a frantic week of fund raising, diplomatic manoeuvring and public announcements (James assured his Scottish subjects that he would return every 3 years though in fact he returned just once).

James reached Berwick on 6th April. The shared crown offered the prospect of an end to five centuries of bitter border disputes so, unsurprisingly, it was a very popular prospect at the border town. His arrival was marked with loud canon fire and he was presented with a purse of gold. He went on to stay with Carey at Widdrington Castle.

Widdrington Castle, near Morpeth

At Newcastle, James was treated to a banquet at the palace of Bishop Tobie Mathew. The bishop made his mark; he was made Archbishop of York and Lord President of the Council of the North just three years later.

James arrived in York on 14th April.

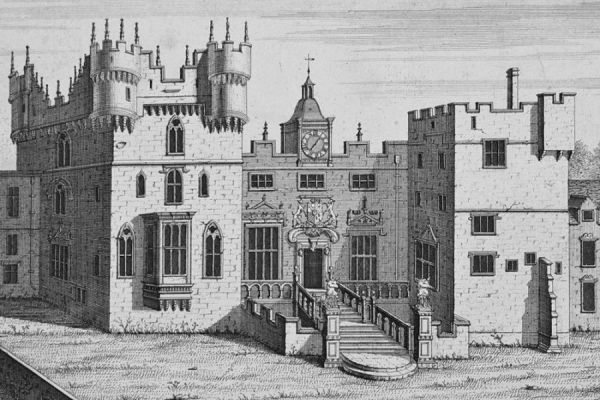

He went on to enjoy an extended stay at Worksop Manor, an impressive mansion owned by the Earl of Shrewsbury and probably designed by Robert Smythson, who had worked on Burghley. There is a retrospective report that during James’ visit, part of the floor in the Great Chamber had fallen down.

Worksop Manor

Near Grantham he was the guest of Roger Manners, 5th Earl of Rutland at his seat, Belvoir Castle.

Belvoir Castle after re-building following the Civil War, with distant views of 1.Bottesford 2.Newark upon Trent 3.Staunton 4.Long Billington 5.Lincoln Minster 6.Denton 7.Sidebroke 8.Barrowby 9.Grantham. Simon and Nathaniel Buck, 1730

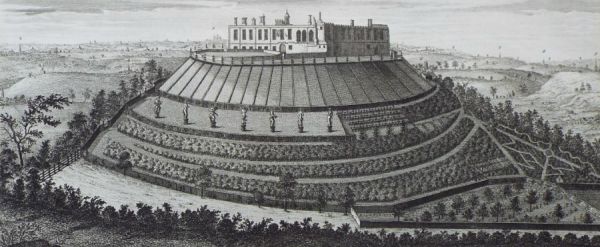

On 27th April James stopped at Sir Anthony Mildmay’s house at Apethorpe 10 miles west of Peterborough. To secure favour with the new King his host presented James with an expensive Barbary horse. A keen huntsman, James returned to Apethorpe 10 times. He encouraged Mildmay’s successor, Fane, to modernise the estate and allowed him to create a 300 acre deer park within Rockingham Forest.

Apethorpe Great Hall. Image Credit – Historic England

At Hinchingbrook he stayed at the home of Oliver Cromwell (uncle of the Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell) describing his stay in his own words as his best reception since he had left Edinburgh. Presents for the king included:

“a cup of gold, goodly horses, deepe-mouthed hounds, divers hawkes of excellent winge,”

while a deputation of the heads of Cambridge University, clad in scarlet gowns and corner caps, attended to present a learned speech in Latin. In return, James I on his Coronation Day made Sir Oliver a Knight of the Bath.

He stayed one night in Royston following the Old North Road to his new capital. Again he was struck by the potential for hunting and liked the town. He returned a few years later, purchasing a number of inns and houses and establishing a favourite though relatively low profile royal residence.

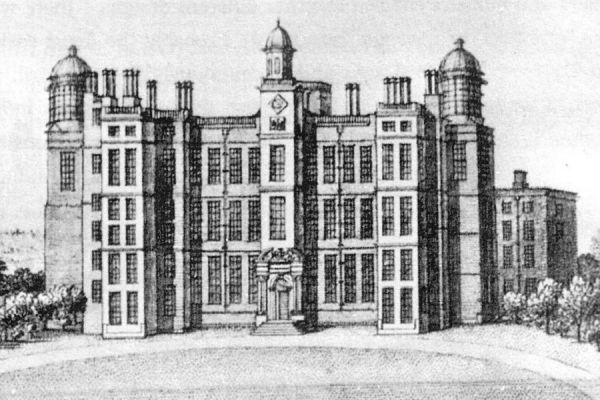

Robert Cecil arranged for the new king to break his journey south at Theobalds House near Cheshunt. A year later James wrote to Cecil requesting stags for him to hunt in the woods and park. In 1607 James acquired Theobalds for his wife, Anne of Denmark, in exchange for Hatfield Palace.

Theobalds Palace

According to the eminent lawyer and Master of Requests, Sir Roger Wilbraham, the king travelled,

“all his way to London entertained with great solemnity and state, all men rejoicing that his lot and their lot had fallen in so good a ground. He was met with great troops of horse and waited on by the sheriff and gentlemen of each shire, in their limits; joyfully received in every city and town; presented with orations and gifts; entertained royally all the way by noblemen and gentlemen at their houses …”.

As a newcomer to England James was keen to establish allies and build on the hopes many had for his reign. Lawrence Stone suggests that some 900 men were knighted in the first 4 months alone.

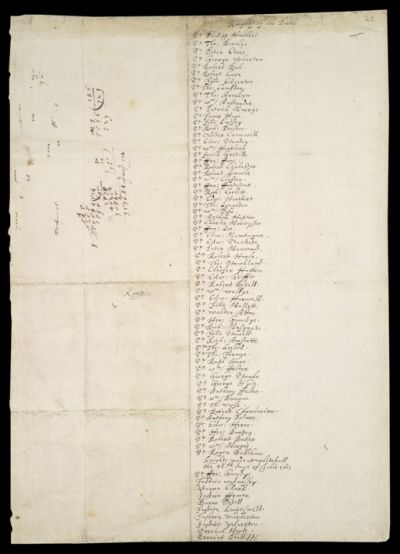

A list by William Cecil, Lord Burghley, of the “Knights of the Bathe” made at the coronation of James I on 25 July 1603

As the king approached London on 7th May (a careful 9 days after the funeral of Elizabeth) he was greeted by the Lord Mayor and Alderman at the top of Stamford Hill. This spot where James first saw the city was later commemorated by a famous inn, “The Three Crowns.”

His coronation as James I of England was held at Westminster Abbey on 25th July. He was the first Scottish king for over 300 years to be crowned sitting on the Stone of Scone (contained within the Coronation Chair).

Public celebrations were deferred until March 1604 because of an epidemic of bubonic plague. This is said to have killed a fifth of London’s citizens: the new king ordered that the sick should isolate for 6 weeks; he also encouraged fund raising for afflicted families. Things improved the following spring and there was enthusiasm to proceed. Gilbert Dugdale described the lavish events to mark his accession:

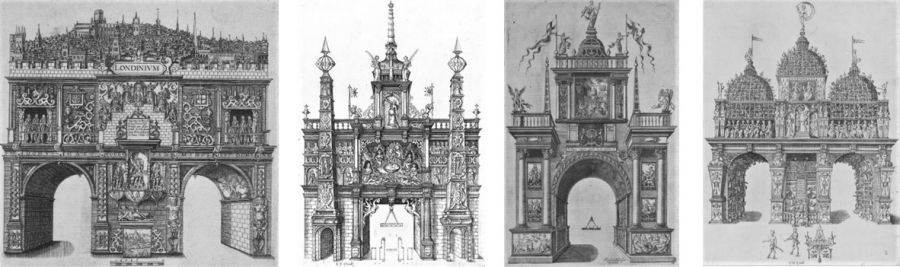

‘fire workes on the water’ and magnificent ‘Pageants’ that were staged on huge wooden arches throughout the city.

There were 7 triumphal arches – imposing constructions, wide enough to span the street, around 25m tall and elaborately decorated with statues, paint and gilding. The arches, funded by London’s multinational merchants, represented different regions, creating a symbolic world tour.

Four of the Triumphal Arches – “Londinium”, “New Arabia”, “The Italians”, “Bower of Plenty”

About King James I of England and King James VI of Scotland

Portrait of James I, c. 1606, by John de Critz (Dulwich Picture Gallery)

James was great grandson of Margaret Tudor who had travelled north along the Great North Road in 1503 to marry James IV and so become Queen of Scotland. He was the son of Mary Queen of Scots. His father Henry, Lord Darnley was assassinated in 1567. He became King James VI of Scotland the same year, when 13 months old, after his mother was compelled to abdicate in his favour.

As an infant, James had councillors ruling in his name, but he took up his personal reign in his mid-teens, in the early 1580s. His childhood was spent at Stirling castle where he was tutored by the stern Presbyterian and humanist George Buchanan.

In 1590, James married Anna, the sister of the Danish king, Christian IV. After her rough crossing of the North Sea several alleged witches from North Berwick were arrested, tortured and executed. Uncovering witches became something of a personal obsession of James.

James was determined to assert his power as king, and to crack down on the ancient custom of “bloodfeuds” between families, and their large armed retinues, particularly in the borders. This was part of his suppression of cross-border raiding in the 1590s as it looked likely that he would succeed Elizabeth on the English throne.

He was a committed Protestant, believing in an episcopalian version where the king was the head of the church, and ruled through bishops. In England James inherited a set of anti-catholic penal laws which he enforced more rigorously than had been expected. The Gunpowder Plot of 1605 served to bring even harsher legislation, though its enforcement later slackened. James’s ecclesiastical legacy endures in his sponsorship of an English translation of the Bible, published in 1611 and subsequently named the Authorised King James Version.

King James maintained his authority despite challenges at home and overseas, and whilst enjoying cultural and recreational pursuits to the full. The finances of the Royal Court were often under pressure; this lay at the heart of a series of stand-offs with Parliament. In fact, he prorogued Parliament in 1604 and again in 1610 and 1621. By luck or by judgement he avoided getting drawn into the Thirty Years War that devastated much of central Europe and his on/off relations with Spain led neither to alliance nor war.

Money raising opportunities were always welcomed. In 1607 James granted a charter to a group of merchants for the formation of the Virginia Company to have a monopoly of the tobacco trade. The company was instrumental in establishing the first permanent English settlement in the Americas. Located on the north-east bank of the James (Powhatan) River it was initially called “James Fort” and later, Jamestown.

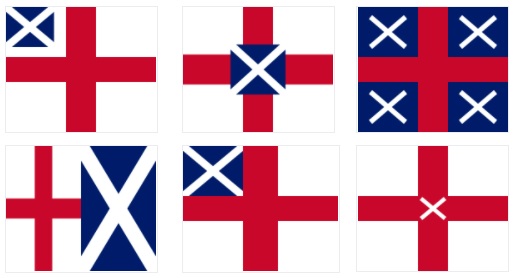

Court culture was cosmopolitan and characterised by conspicuous expenditure. Shakespeare included references to the new king in his works. Flemish painter, John de Critz undertook lavish portraits of the King. Designs for the Union Jack flag were commissioned. Emblematic jewellery, including the “Mirror of Great Britain” was celebrated. Meanwhile, James was ever keen to escape the city and pursue country pursuits and raucous parties with close friends such as George Villiers.

James died in 1625 and was succeeded by his son, Charles.

A range of design proposals were made for a union flag combining the St George’s Cross of England and the Saltire of Scotland. The version below was adopted in 1606.