Edinburgh Coaching Inns and the Great North Road

Arguably it was the Great North Road and the development of coaching services which was the precursor to the emergence of inns and hotels in Edinburgh. The city did not have the tradition of medieval inns seen in say London, Stamford or Grantham. This had long been a concern more widely in Scotland prompting the government to pass legislation in 1425 to encourage travellers staying in burgh towns to use commercial inns rather than stay with friends and acquaintances. Early visitors from the south complained bitterly that their coaches took them to a “stabler’s”. Guest houses and lodgings within the crowded city tenements often needed to be separately arranged.

Harper relays this tale of a 1770s traveller:

“On my first arrival, my companion and self, after the fatigue of a long day’s journey, were landed at one of these stable-keepers’ in a part of the town which is called the Pleasance; and on entering the house we were conducted by a poor girl without shoes or stockings, and with only a single linsey-woolsey petticoat which just reached half-way to her ankles, into a room where about twenty Scotch drovers had been regaling themselves with whisky and potatoes. You may guess our amazement when we were informed that this was the best inn in the metropolis, and that we could have no beds unless we had an inclination to sleep together, and in the same room with the company which a stage-coach had that moment discharged.”

It should be remembered that the route of the Great North Road was never singularly defined. There have always been very different options for traveller between Edinburgh and North Yorkshire. This is reflected in the location of inns and stables in Edinburgh, which were often located close to the different gates of the old city. The East Road was via Newcastle, Morpeth, Berwick, Dunbar, with the Scottish capital being entered by the Water Gate. The Mid Road cut inland via Wooler or via Kelso and Lauder, entering the city at the Pleasance. The West Road via Carlisle and Selkirk entered at Bristo Port.

About Edinburgh Coaching Inns

Coaching inns did emerge in the 18th century as providers of the horses invested in this opportunity. The early inns were located outside the city walls close to the major routes entering the city: a particular concentration was in Pleasance, or it’s continuation, St Mary’s Wynd (now St. Mary Street). More modern inns with improved facilities were then established in the New Town as it began to take shape from the 1760s.

[Traditionally it was common for inns to be known by both a name (such as White Horse) and the name of the landlord: given the propensity in the 18th century for landlords to migrate from one establishment to another that sometimes makes it difficult to follow the history of individual inns. If you spot any errors do please let me know!]

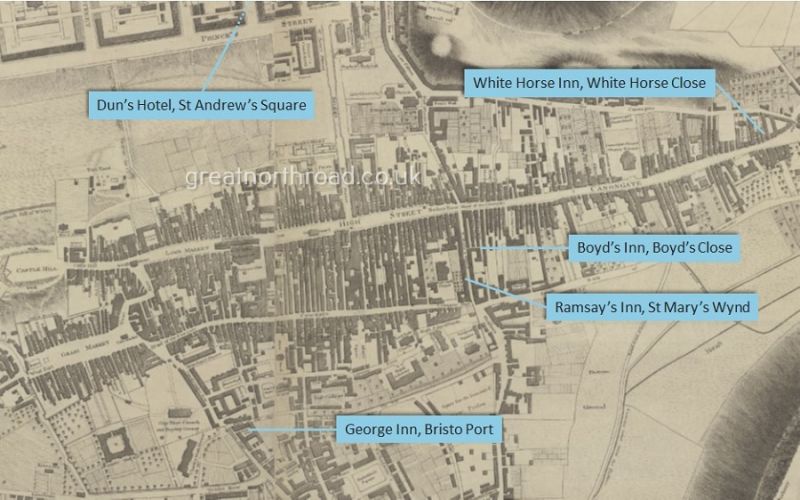

Edinburgh Coaching Inns on Alexander Kincaid’s 1784 Map. An interactive online version of this map can be found at the National Library of Scotland.

The White Horse Inn, Canongate

White House Close in the late 19th century and today

The inn was built in the early 17th century by Lawrence Ord who is said to have adopted the name because Mary Queen of Scots stabled her favourite white horse there. In 1639 the White Horse Inn featured in the “Stoppit Stravaig” incident. King Charles I was seeking peace with the Covenanters and had come to Berwick. A group of Scottish noblemen had gathered at the inn before setting off to negotiate with the king but presbyterian ministers encouraged a mob to lay siege to the inn and prevent them from leaving. Only the Marquis of Montrose escaped to join the king.

The White Horse Inn was positioned well for coaches travelling the coastal route of the Great North Road, but less so for the more popular central routes. This may have been one reason for its relative lack of success in the 18th century. The inn closed in the late 18th century though the building survived. Today White Horse Close is one of the most picturesque parts of Edinburgh’s Old Town: its heavy makeover has prompted the jibe that it is now “a Hollywood dream of the seventeenth century”.

Boyd’s Inn (White Horse), Boyd’s Close

Boyd’s Inn: Canongate entrance and stairs to hall

Another White Horse was more commonly known as Boyd’s Inn. It was located in Boyd’s Close which seems to have had entrances from both Canongate and St Mary’s Wynd. Described as more modern, and larger than Ramsay’s, they both had the principal rooms above the stables. In 1773 Dr Samuel Johnson stayed at Boyd’s Inn and was not impressed.

Johnson “asked to have his lemonade made sweeter, upon which the waiter with his greasy fingers, lifted a lump of sugar, and put it into it. The Doctor, in indignation, threw it out of the window.”

James Boswell, Johnson’s companion on his Hebridean journeys

Caricature of Johnson and Samuel in Edinburgh High Street by Samuel Collings

The site had been used as stablers’ premises since at least the 1630s when it was held by James Hamilton. James Boyd took control in the mid 18th century. A 1771 review was less than complimentary:

“crowded and confused”, the master living in the stable, the mistress “not equal – to the business.”

Boyd had had enough by 1779 and sought a tenant for the inn:

‘To be let immediately and entry to at Whitsunday next for such a term of years as shall be agreed upon that large commodious and well – frequented inn at the head of the Canongate, called Boyd’s Inn, consisting of two dining-rooms, a small outer room or parlour, 13 bedrooms and closets, besides servants’ bedrooms, a small writing-closet, a convenient large kitchen and larder, wine cellar with catacombs, coal and ale cellars; together with stables for upwards of 50 horses wherein are 40 stalls; as also backyard, pump well and coachhouse, which will contain four or five carriages, and a convenient poultry house and other offices. The loft above the stables will hold between two and three thousand stone of hay, and there is an excellent corn loft.’

The inn was let to John Dumbreck, who had previously been in the service of Boyd, and who in 1790 went on to take over Dun’s Hotel in the New Town. Dumbreck built a strong coaching business. The Edinburgh and London Fly left at 2am to reach London in 4 days. It was also the terminus of the Edinburgh and Aberdeen Fly, as well as services to Kelso and Leith.

Ramsay’s Inn (Red Lion), St Mary’s Wynd

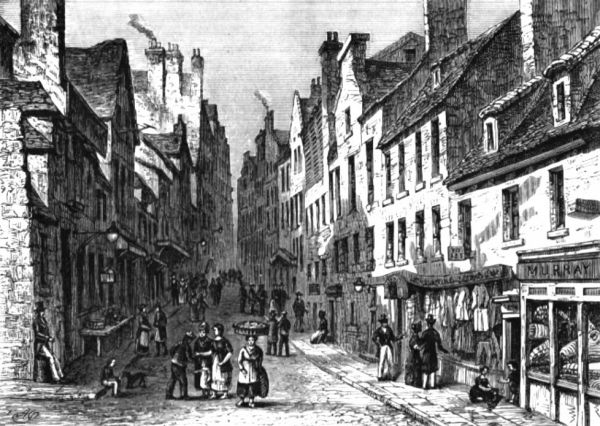

St Mary’s Wynd from the Pleasance – 1829

Peter Ramsay’s Red Lion Inn was an adjunct to his stabling business in St Mary’s Wynd. By all accounts his business was very successful and it was described as follows in 1776:

“a good house for entertainment, good stables for above one hundred horses, and sheds for above twenty carriages.”

Ramsey retired in 1790, and when he died four years later his estate was worth some £30,000. St Mary’s Wynd in the 18th century was a little less genteel than is suggested in the 1829 image above. Ramsey kept pigs which were allowed to roam the street for scraps: there is a story told of the Duchess of Gordon and her sister, when children, riding on the back of pigs! By the 1860s it had become “one of the most wretched slums in the city, a narrow and stifling alley”: targeted by the 1867 Improvement Act, the lane was widened to form St Mary’s Street.

Dun’s Hotel (later Dumbreck’s Hotel), St Andrew Square

James Dun took over the White Hart Inn “at the foot of Pleasance” in 1772, running a coach to Newcastle three times each week. In 1776 Dun was the first to move into the New Town, taking the upper floors above John Neale’s haberdashery shop in St Andrew’s Square. He displayed a gilded sign outside saying “Dun’s Hotel” which prompted a complaint from the Lord Provost objecting to the use of the foreign word “hotel”.

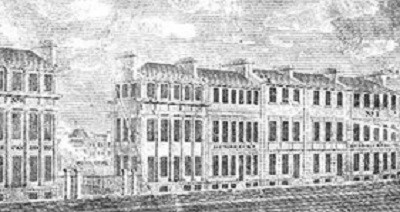

The Dumbreck’s Hotel in St. Andrew Square, Edinburgh. c 1800

Dun’s Hotel is the building on the extreme right of the above image and was acquired in 1790 by John Dumbreck. He also acquired the building on the left. His son then took over both properties creating “Dumbreck’s Hotel”, spreading into the buildings in between. It became the best known hotel in the New Town and regularly featured in literature, including Robert Louis Stevenson’s “St Ives”.

The George Inn, Bristo Port

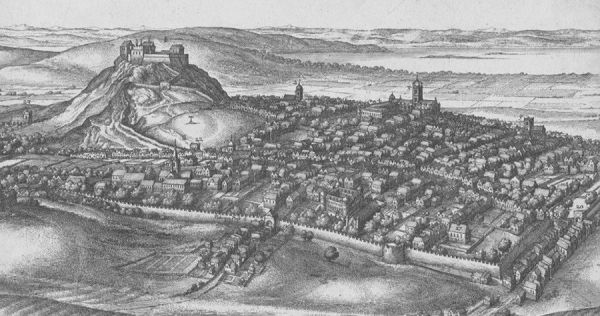

The City of Edinburgh from the South 1670, Wenceslaus Hollar

The inns in Grassmarket near the West Port were less relevant to the coach routes to northeast England, but one close to the southern gate, Bristo Port, deserves mention. The George Inn became a sizeable establishment in the 18th century and was made famous by Walter Scott. Remnants of the building still survive.

The George was located just outside the Greyfriars or Bristo Port gateway of the 1515 Flodden Wall. The buildings have been recorded since the 17th century and were being used as an inn by the early 18th century. The Caledonian Mercury of 2nd March l736 describes George Robertson as a “Stabler at Bristow port” with an inn often used by the Newcastle carriers: he was fleeing justice – and his character was later adopted by Scott in his 1818 novel, “Heart of Midlothian”.

The stables were re-built in the 1750s and by the 1770s the inn was being operated by John Cockburn who appears to have tapped into the fast-developing coaching business. In August 1775 the four-day Flying Diligence service to London by way of Carlisle was announced to depart the George Inn thrice weekly. Prior to another change of ownership in 1779 the George was described:

It consisted of eighteen rooms, besides garrets, servants accommodation, and cellarage. There was also stabling for fifty horses, with shades for seven carriages, one of which could be used as a stable if necessary. The George could be made the most commodious and complete Inn about Edinburgh at a small expense.

William Wallace, the new owner, announced:

“that he had taken and fitted up in the neatest and most elegant manner, the large and commodious Inn, the George, at Bristo Port…. well known to be among the first in Scotland… he has laid in a complete assortment of the best liquors of every kind and the utmost attention will be bestowed on such horses and carriages as are entrusted to his care.”

Additional coaching services from the George included the Edinburgh and Ayr Diligence, and the Dumfries Diligence.

In the early 19th century coach passengers tended to drift to the larger and more modern hotels of the New Town but the George lived on, serving the needs of the carriers and the humbler travellers come to do business in Edinburgh’s many markets. The George finally went out of business with the advent of the railways: ironically, in 1845 the site is recorded in the name of Howie and Co who were warehousing goods for the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway.

The site was redeveloped in the 19thcentury but the inn’s basements are thought to underlie the current properties known as 3 Bristo Port and 8-10 Bristo Place. This image taken in 2006 resides in the Canmore collection of Historic Environment Scotland.

More Information about Edinburgh Coaching Inns

Some Inns of the 18th Century, James Jamieson (see page 121)

Canongate Tollbooth