Whittlesea Mere and the Great North Road

Until the 1850s Whittlesea Mere was one of the largest lakes in England. It had long been a rich source of fish and wildfowl – and by the 18th century it was also attracting visitors from near and far who enjoyed sailing and ice skating.

The now drained Mere was a couple of miles to the east of the Great North Road near Stilton. It was located on an old course of the River Nene, where it reached the boggy fenland and started to meander aimlessly towards the North Sea.

The Mere was both a destination accessed from the Great North Road and a notable landmark for those travelling its length. Famous travel writers who were struck by the lake included Celia Fiennes, the daughter of a colonel in Cromwell’s army, who rode side-saddle through every county in England. In 1697 she wrote in her diary:

Ffrom Huntington we came to Shilton 10 mile, and Came in Sight of a great water on the Right hand about a mile off wch Looked Like Some Sea it being so high and of great Length: this is in part of the ffenny Country and is Called Whitlsome Mer, is 3 mile broad and six long. In ye Midst is a little jsland where a great Store of Wildfowle breeds, there is no coming near it; in a Mile or two the ground is all wett and Marshy but there are severall little Channells runs into it wch by boats people go up to this place. When you enter the mouth of ye Mer it lookes fformidable and its often very dangerous by reason of sudden winds that will rise Like Hurricanes in the Mer, but at other tymes people boate it round the Mer with pleasure.

Facilitated by the latest pumping technology, the lake was removed in the 19th century in the name of progress (and higher land values).

Image at top of page: Whittlesea Mere with Yaxley church in the foreground depicted in the Illustrated London News in April 1851. This was alongside a story about the draining of the lake. The accompanying notes point out small details such as the steam train on the recently built London to Peterborough railway line.

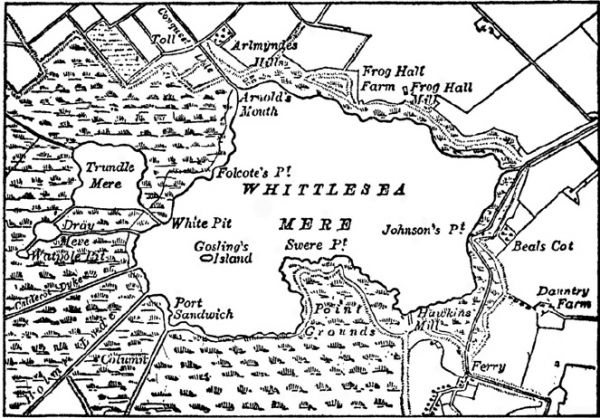

Extract from Bowen’s 1760 “Accurate Map of the County of Huntingdon”, showing Whittlesey Mere and “Watling Street being the Roman highway from Huntingdon”

Whittlesea Mere – Origins

The fenland basin stretching from Peterborough to the Wash is only marginally above current day sea level and has experienced regular flooding from both sea and rivers since the glaciers retreated 10,000 years ago. The deciduous forest of the Neolithic was lost as the increasingly sodden ground promoted steady growth of sphagnum moss, with progressively deepening layers of peat. In the late Neolithic the Fen edge was at about the 1m contour but by the late Medieval period it was as high as the 3.6m contour. Meres were created where the drainage of water was impeded. Dating of the marls deposited at the base of Whittlesey Mere point to its formation in the first century BC.

The first historical reference to Whittlesey Mere appears in the Anglo Saxon Chronicle when under the year 657 it is reported to have been granted by King Wulfhere to the newly established Abbey of Peterborough (then Medehampstede).

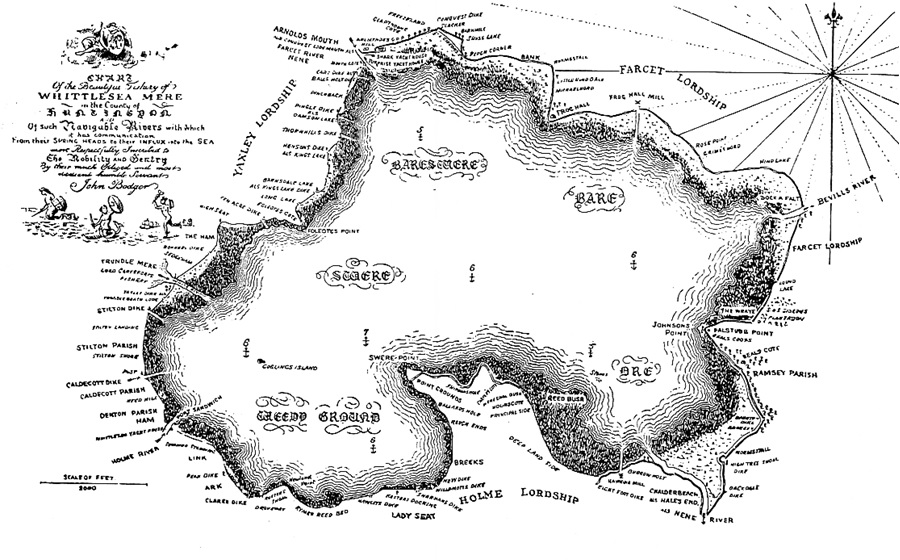

The size of the lake in historical times is uncertain. In the early 17th century William Camden described it as “six miles in length and three in breadth that cleer, deepe and fishfull Mere named Wittlesmere.” These popularly quoted dimension are extreme – and can only reflect times of inundation. The map drawn by Bodger in 1786 shows the Mere to be 2 miles by 1.5; this agrees well with the area of marly deposit seen in the local geology.

Whittlesea Mere – A Monastic Property

The Domesday Book records Whittlesey Mere as a settlement in the hundred of Normancross and the county of Huntingdonshire. With just 2 households (both fishermen) it was the property of the abbeys at Peterborough, Ramsey and Thorney. The fishing grounds of the lake were divided into ‘boatgates’ (one boat, three men and specific size of nets) each of which was licenced to generate income. From 1261, nearby Sawtry Abbey also held fishing rights and a channel was cut to facilitate access (Monks’ Lode).

The Mere was surrounded by extensive reed beds which were also regarded as a valuable resource. Reeds were sold for thatching and for plastering ceilings and floors. Sedge was used for thatching and for animal bedding. Woolly heads of bulrushes were stripped off to stuff bedding.

The monasteries remained in charge until their dissolution in the 1530s, when abbey lands were sold off. The Cromwell family (Richard Williams) bought both Ramsey and Sawtry Abbeys along with most of the fishing rights. Those held by Peterborough Abbey went to the Dean and Chapter of the cathedral.

Originally, the Mere formed part of the River Nene as it flowed from Peterborough to Ramsey and beyond. In the 15th century Bishop Mortion’s Leam created an alternative straight channel between Peterborough and Wisbech.

The clergy continued to enjoy the delights of Whittlesey Mere and perhaps helped its transition to recreational use. In a volume of Latin Poems James Duport, Dean of Peterborough, provides a humorous account of a water party in 1669 when William Pierrepont entertained the Bishop on the mere, near Frog Hall. The banquet began with melons and port wine; next a venison pasty; rounds of beef; and shoulders of mutton. Amongst references to Greek mythology – “Whittlesey Mere had become a second Bosphorous.” After these substantial viands came poultry, pullets with bacon, salted tongues and another wine. The last course consisted of roast apples, tarts, cakes, another wine and cider. After the banquet the host produced tobacco: Incipit innocui fumos haurire Tabaci.

Lord Orford’s Great Adventure

In 1774 the Rt Hon George Walpole, Third Earl of Orford, High Steward of Yarmouth and Kings Lynn, and Lord of the Bedchamber to George II and George III, embarked on an epic voyage up the Nene to Whittlesey Mere. Whilst other explorers, such as James Cook, were reaching the New World, “Admiral” Orford preferred more prosaic adventures but with plenty of opportunities for hunting, horse racing, drinking and visits to local dignitaries.

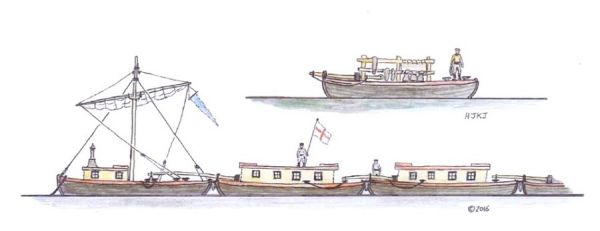

Image credit – HJK Jenkins – The Fenland Lighter Project

His flotilla of fen lighters included The Whale, The Alligator, The Shark, The Dolphin, The Fireaway Bumketch (a punt gun boat) and The Cocoa Nut Victualler (store barge). Amongst the party was a horse called “Hippopotamus”. Thomas Roberts, a volunteer aboard, reported:

9th Day. Sunday, 24th – The Ships kept their station in the Meer. A great number of boats, with the inhabitants of the Country, came to view us, and spent the afternoon in sailing about. Nothing particular happened in the course of the day, and at night all went to bed in the Fleet.

10th Day. Monday, 25th – Lord Sandwich, attended by Captains Hotham and Walsingham, Mr Bates and Mr King breakfasted with the Admiral on board the Shark, and invited him, Mrs Turk, etc to dinner board his Fleet. The dinner consisted of four dishes of boiled Pike and Perch, which had just before been caught in the Meer, and a great variety of cold meats, tongues, Chickens etc. Dinner ended, his Lordship, Mr Bates, and Mr King entertained the Company with a few Catches; and the rest of the day was spent in sailing on the Meer, and taking up the trimmers, by which means his Lordship had taken above twenty brace of very large Perch and Pike.

[Lord Sandwich was First Lord of the Admiralty at the time.]

Whittlesea Mere – Wildfowl and Fishing

Awareness of Whittlesea Mere was further enhanced a few years later when Stilton land surveyor John Bodger published his annotated “Chart of the Beautiful Fishery of Whittlesea Mere”. Curiously the map (and a later Ordnance Survey map) names the outlet of a small creek “Port Sandwich”.

Financed through subscriptions, Bodger’s map included detailed information to facilitate navigation and fishing, with river routes, distances and elevation changes from a variety of places. Beneath the map the description reads:

WHITTLESEA MERE , the most spacious fresh water Lake in the South ern part of Great Britain, on which have been exhibited several Regattas, and Ice Boat Sailing, is situated on the Northern side of the County of Huntingdon, about thirty-eight miles West of the German Ocean; six miles down the Nene from the City of Peterborough, and two miles and three-quarters East of Stilton. Its surface is 1,570 square acres, and in general the Depth varies considerably, and its circumference eight miles and three-quarters, abounding with a great variety of Water Fowl, and the following species of Fish, vizt: Pike, Perch, Carp, Tench, Eels, Bream, Chub, Roach, Dace, Gudgeons, Shallows, etc, and in the summer months is visited by many of the Nobility and Gentry from various parts, but at times is violently agitated without any visible cause, and is fed by the waters of a large tract of country, whose overplus makes its way down to the Sea.

The aptly named Gosling Island provided an ideal focus for itinerant wild fowl.

“Whittlesea mere was also a favourite resort of the wild-fowl hunter. For this purpose a sledge on bone-runners was required. In front of this sledge a fence of upright reeds was arranged which partially concealed the projecting muzzle of a long duck-gun carrying a heavy charge of shot. Kneeling in the hinder part of the sledge, and punting himself along with two iron-shod sticks, the sportsman was eanbled to approach to within a short distance of the islands of sedge, which were to be found near the shores of the Mere, and were frequented by flocks of duck, teal, widgeon and other wild fowl.”

Heathcote and Tebbutt, 1892

Boating and Ice Skating

By the 19th century it was not unknown for the lake to all but dry up in summer so its value as a fishery would have been declining. However, for recreational boating and for winter sports when frozen it was a big draw.

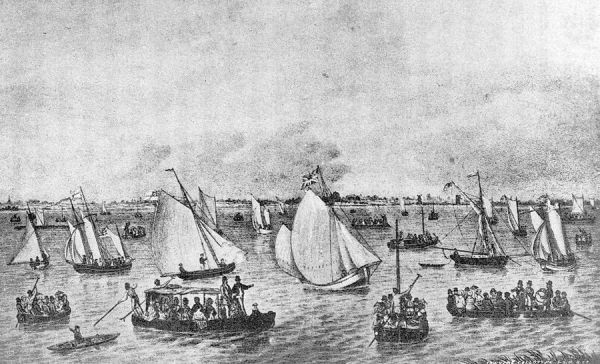

Whittlesea Mere was famous for its yachting and boat races. The June regatta featured picnics, brass bands and dancing at Swere Point and Black Ham as dozens of boats competed for a variety of prizes.

Whittlesea Mere Regatta, June 1841

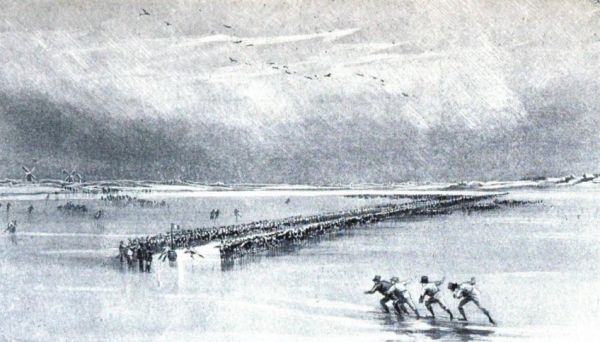

During harsh winters, local people had long been drawn to the Mere to go skating. Using bone or metal skates, by the 1700s there were keenly fought races for prizes of goods or money. During the winter of 1822-3 an ice fairs was held where “stalls and booths were erected, chestnuts roasted and bands of music played”. In 1840 a thousand acres of water was frozen over and 6,000 people gathered at the Mere to skate and watch races run over a two-mile course.

A Race on Whittlesea Mere in 1835 (from a sketch by J M Heathcote)

The Draining of Whittlesey Mere

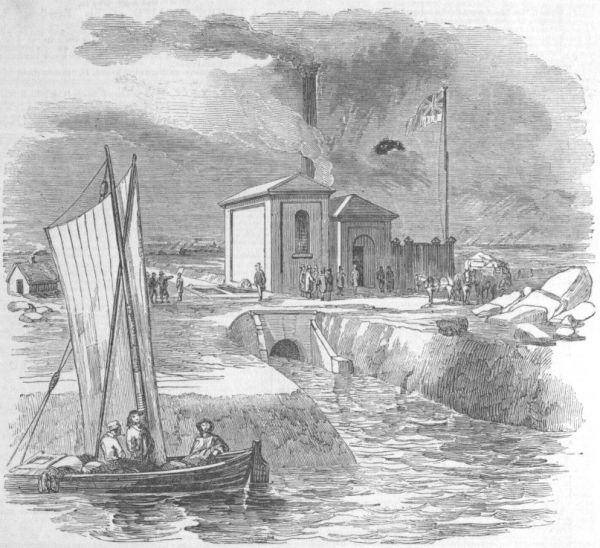

Bevill’s Leam of the 1630s, and other gravity dependent drainage systems, had been drying out neighbouring fenland for centuries. Water levels in Whittlesea Mere fell but it remained an area of wetland. A concerted drainage project, funded by local landowners and given parliamentary powers in the 1840s, opened the way to tackle what by then was often cited as “a nuisance”. It also required the latest steam technology – notably a version of Easton & Amos’ Appold pump exhibited at the Great Exhibition of 1851. With a 25hp engine the pump could discharge 16,000 gallons per minute with a 6-foot lift.

The Illustrated London News sums up the positive mood associated with the initiative:

“After having been accustomed for so many years to see Whittlesey Mere as nothing but a flat scene – fenny, watery, swampy, and unproductive – it will be almost startling to see, at the touch of the genius of improvement, the water flow into canals, the swamps become green pasture grounds, the fens flooded over with a golden sea of ripened corn, and farms and homesteads gathering round them the treasures of the soil.”

Whittlesea Mere prior to its drainage (Miller and Skertchly, 1878, after 1824 Ordnance Survey map)

Drainage of Whittlesea Mere, Appold’s Pump. Illustrated London News, 22 November 1851

Tons of pike, perch and eels were lifted from the receding waters and then the newly revealed bed of the lake gave up secrets of its past.

A boat cut in one piece from the trunk of an oak, “black from age”, 27 feet long and 4.5 feet wide. This is like the multiple Bronze Age boats recovered from nearby Must Farm, and other ancient fenland waterways. A metre long, double edged medieval sword and an ancient spear were also recovered.

Four massive stone blocks (with mason’s marks) from the quarries at Barnack, near Stamford. These are likely to have been lost whilst being transported by barge for the construction of the great monasteries at Ely or Ramsey.

A silver censer and incense boat were found a little west of the eastern boundary dyke. A rams head decoration suggests their intended destination was Ramsey Abbey. The items found their way to Elton Hall and now reside in the V&A museum.

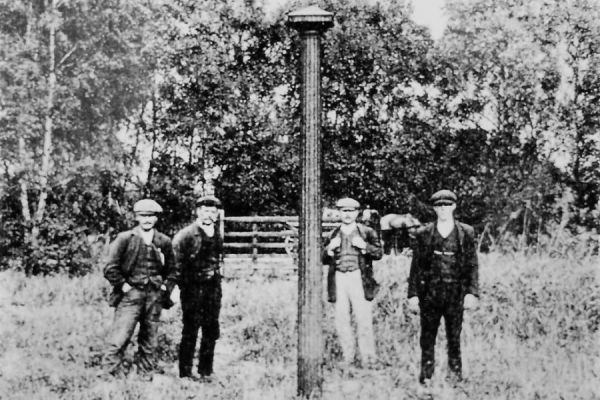

William Wells, Lord of the Manor at Glatton, erected an iron post from Crystal Palace to record the shrinkage of the peat (this succeeded three earlier wooden posts). The surface level in 1848 was recorded as 5 feet 7 inches. The present land surface is more than 13 feet lower.

A Partial Restoration

The draining of Whittlesey Mere created productive agricultural land but at the expense of unique habitats and associated flora and fauna.

Local poet, John Clare, wrote:

“a dwarf willow grows there about a foot high which it never exceeds. It is also a place very common for the cranberry that trails by the brink of the mere. There are several water weeds too with very beautiful or peculiar flowers that have not yet been honoured with christenings from modern botany.”

Collectors of moths and butterflies came from as far as London. Reed cutters guided the tourists and sold the larvae of the Reed Tussock (Whittlesea Satin Moth) for a shilling per dozen. Swallow Tail Butterflies were abundant. The most prized was the Large Copper Butterfly – now extinct in Britain.

The Great Fen Project is currently reclaiming land from intensive farming with a view to, at least partially, restoring the rich wetland fen.

More Information about Whittlesea Mere

England’s Lost Lake, Paul Middleton, FastPrint Publishing, 2018

Lord Orford’s Voyage Round The Fens – 1774

The Fenland, Past and Present, Sydney and Skertchly, 1878