New Towns and the Great North Road

The first “Garden Cities” and “New Towns” were located along the Great North Road.

The accelerated population growth of these urban centres has increased the numbers who travel along and live close to the road. The evolution of the A1 through the Home Counties during the 20th century was indeed shaped by these emerging towns.

Travelling north from London we first come to Hampstead Garden Suburb. Through Hertfordshire there’s Hatfield, Welwyn, Stevenage and Letchworth. Peterborough was a late comer of the 1970s and 80s. Then in the Northeast there’s another cluster of new towns including Newton Aycliffe and Washington.

About New Towns

The Garden Cities and New Towns of the last 130 years have their roots in the 19th century when enlightened industrialists and campaigners sought new urban models which avoided the overcrowding and poor sanitation which came to characterise our fast-growing cities.

Model villages were created by company owners for their industrial workers. Robert Owen’s New Lanark on the River Clyde in Scotland was developed from 1800; Titus Salt’s village of Saltaire next to the River Aire was commissioned in the 1850s; George Cadbury set up Bournville near Birmingham in the 1890s; on Merseyside William Lever established Port Sunlight which included green spaces, parkland, and public buildings.

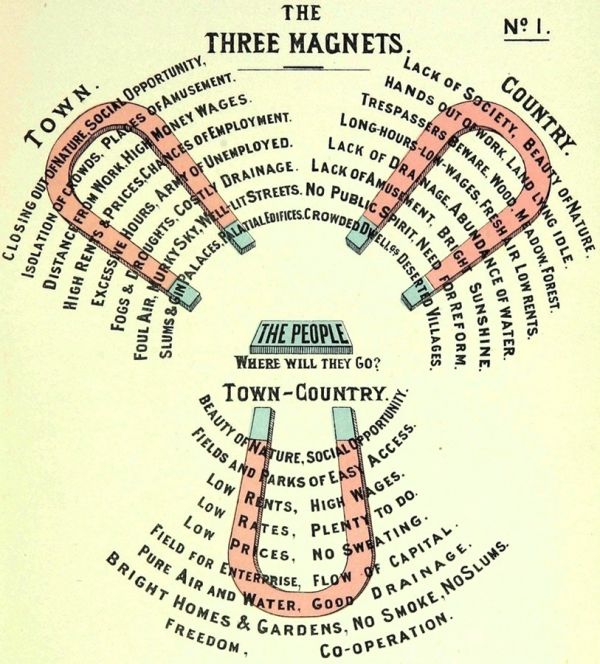

These planned townships were impressive but focused on individual factory sites and at most had populations of a few thousand. They did however help inspire social reformers such as William Morris and Ebeneezer Howard to propose the concept of planned communities which combined the best of both urban and country living.

The Three Magnets from Garden Cities of To-morrow, 1902, Ebenezer Howard

The early manifestations of this new approach were dependent upon private developers who saw that with improving rail and road infrastructure the concept of satellite communities outside the bigger cities would appeal to many.

After the second world war there was a stronger top-down push to rid the cities of slums and create modern, vibrant communities; to disperse people from bombed-out and overcrowded cities; to create a “New Jerusalem”!

John Reith was appointed chair of the New Towns Commission which recommended towns of up to 60,000 built on greenfield sites, featuring predominantly single-family low-density housing, community integration, neighbourhood infrastructure and parallel investment in jobs and industry.

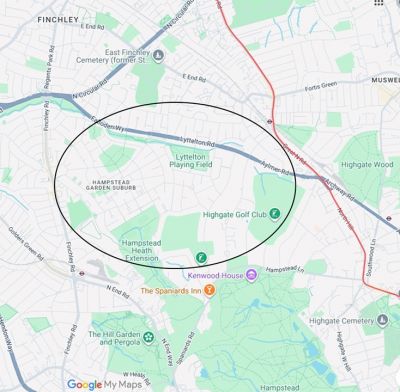

Hampstead Garden Suburb

Hampstead Garden Suburb was the brainchild of Dame Henrietta Barnett. It grew out of the same train of intellectual thought as the Garden Cities but was more akin to the middle-class residential suburbs which later proliferated as mass transit systems allowed people to distance their residence from their place of work.

Henrietta Barnett. Image Credit: National Portrait Gallery

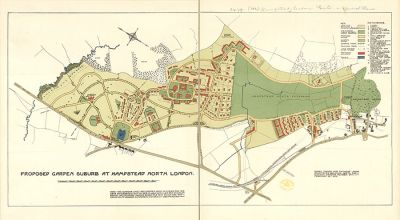

Henrietta was wife of the vicar of St Jude’s, Whitechapel, and became an advocate for better housing for the poor. The couple had a house overlooking Hampstead Heath at Spaniards End and to the north of this lay acres of heath and farmland which she persuaded Eton College to sell. She set up the Hampstead Garden Suburb Trust as a development vehicle and employed Raymond Unwin to draw up a master plan for a fee of £100. Unwin had worked with the Rowntrees on New Earswick and was also involved at Letchworth (he went on to become President of the Royal Institute of British Architects in the 1930s).

Construction began in 1907 and the suburb ultimately grew to over 800 acres. Edwin Lutyens was a consulting architect and he designed many of the principal buildings.

The aim was for different social classes to share the same community, for the houses to be non-uniform and to be built at a low density to ensure the area was not overcrowded. There were to be green spaces which retained the existing woodland, hedges, and trees. Allotment gardens would allow residents to grow their own fruit and vegetables.

1905 Plan for Hampstead Garden Suburb. Image Credit: Barry Parker and Raymond Unwin.

Location of Hampstead Garden Suburb relative to the route of the Great North Road (shown in red)

Image Credit: Google

Hatfield

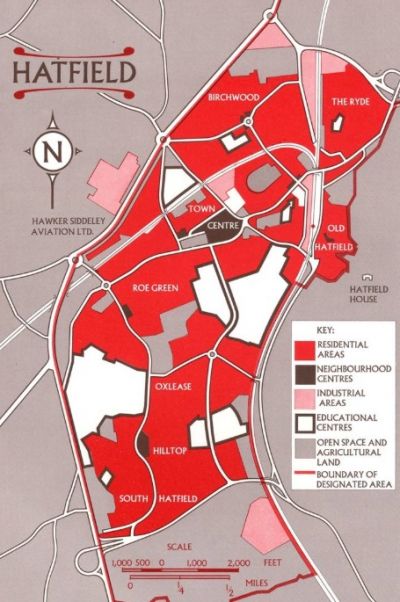

Hatfield was designated as a new town in 1948, alongside the existing Welwyn Garden City. The intent was to grow population from 8,500 to 25,000 supporting the rapidly expanding workforce of the De Havilland Aircraft Company.

The town was separated from Welwyn by a thin strip of Green Belt. The twin towns shared “Development Corporation” personnel until the organisation was wound up in 1966.

Hatfield Master Plan. The Great North Road (A1) runs north-south forming its western boundary

Welwyn Garden City

In 1918 Ebeneezer Howard spotted a site at the village of Welwyn and he raised the cash to buy the 2,400-acre shooting estate from its debt laden owner. Backers included Harmsworth’s Daily Mail which had been sponsoring the Ideal Home exhibition since 1908. It built some of the first houses free of charge – there was even a Dailymail Village.

The Welwyn Garden City Company was established to own and operate the town as had been done in Letchworth. Welwyn went on to be designated as one of the post war new towns with a Development Corporation taking over from the original developer. The intention now was to triple the population to 25,000. The original Garden City masterplan drawn up by Louis de Soissons followed Garden City design principles, with tree-lined boulevards and a neo-Georgian town centre.

Louis de Soissons’ Welwyn Garden City masterplan, June 1920. Image Credit: Louis de Soissons Limited CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

As illustrated by this 1939 film, bypasses were built to take the A1’s through traffic away from the new town centres.

Stevenage

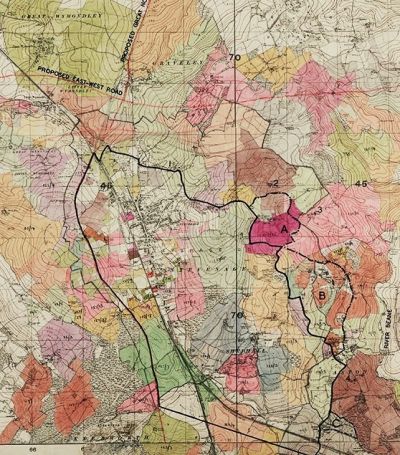

Stevenage was the first New Town to be designated under the New Towns Act 1946. The intention was to increase population tenfold from under 7,000.

Plan of “proposed satellite” at Stevenage, 1946. The realignment of the A1 is anticipated. There is also a putative East-West trunk road which was never built. Image Credit: Hertfordshire Archives and Local Studies

By 1955 the master plan identified 6 discrete new neighbourhood communities, a pedestrianised town centre and a separate industrial area. These all emerged at pace during the next 20 years, connected by new roads and a separate network of paths and cycle tracks.

The A1 was diverted from its historic route along the High Street of the Old Town in 1962. There had been plenty of scepticism in the 1950s that the infrastructure needed for the new town would never be provided, as illustrated by this parliamentary question of 1956:

I should like to draw the attention of the Minister to Stevenage. Here a new town has been built on one side of the Great North Road and an industrial estate on the other. As was to be expected, conditions on Al at that point have become dangerous and difficult. Indeed, the local authorities were obliged to put a Bailey bridge over the Great North Road for the benefit of the workpeople going between the new town and the factories…… Such is the tale of muddle, indecision and procrastination over the re-building of the Great North Road

Mr. Barnett Janner

Roundabout at junction of St George’s Way, Six Hills Way and Monkswood Way – taken from roof of Southgate House. Image Credit: Stevenage Museum

The vast English Electric guided weapons factory under construction in 1955. The A1(M) now runs alongside. Image Credit: Historypin

Letchworth

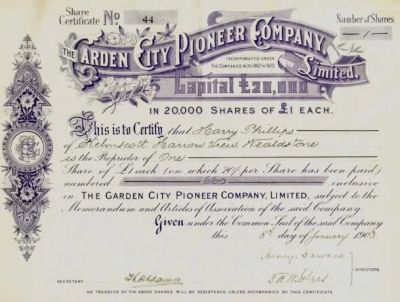

The Garden City Pioneer Company was formed in 1902 (directors included George Cadbury and the subscribers included Lever). They targeted potential sites around London but homed in on Letchworth Hall Estate.

Share certificate, signed by Ebenezer Howard, for the Garden City Pioneer Company Limited. Image Credit: The Garden City Collection, Letchworth Garden City.

First Garden City Ltd was formed in 1903 to own and operate the town according to Howard’s principles just 5 years after he had published his vision for Garden Cities. A master plan was drawn up in 1904 then competitions held for house designs, attracting 60,000 to two exhibitions. The rules stipulated that the properties were to cost no more than £150 to construct and to contain a living room, scullery and 3 bedrooms. There was no requirement for a bathroom but most contained a WC.

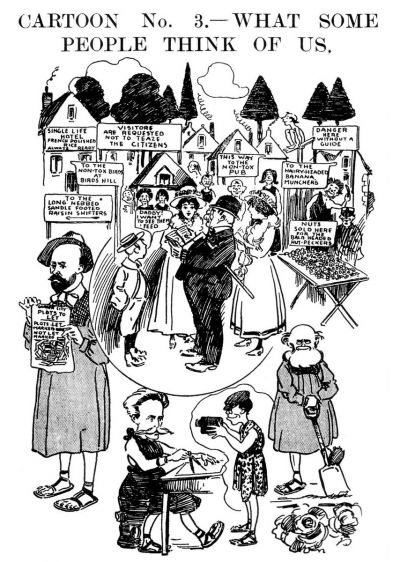

The idealism of the Garden City experiment attracted many who others saw as cranks. In his Letchworth Diary, Charles Lee jokes that a typical Garden citizen was:

clad in knickerbockers and, of course, sandals, a vegetarian and a member of the Theosophical Society, who kept two tortoises which he polishes periodically with the best Lucca oil. Over his mantlepiece was a large photo of Madame Blavatsky and on his library shelves were Isis Unveiled and the works of William Morris, HG Wells and Tolstoy.

The “non-tox pub” in the cartoon below refers to the alcohol-free Skittles Inn.

Caricature of Letchworth residents, c1909. Image Credit: Louis Weirter

Letchworth was conceived before car ownership and road transport took off so, compared to the subsequent New Towns, road infrastructure was quite limited.

The Spirella wire spring corset factory in 1935. Image Credit: Hertfordshire Archives and Local Studies

Peterborough

Along with Milton Keynes and Northampton, Peterborough was in the late-1960s “third wave” of New Towns when the aspiration for population expansion was much higher – growth of 100,000 in the case of Peterborough.

Much was learnt from the earlier experiments, not least when it came to road infrastructure and shopping centres, where Wyndham Thomas and the Development Corporation team drew heavily on their visits to the US. A full ring of Parkways defined the new town, integrated with the existing A1, A47 and A15 through routes.

The 1985 Parkway bridge over the Nene to the east of the city. Image Credit: Rex Gibson

Whilst the Development Corporation was wound up in 1988 Peterborough has continued to grow, not least because of its strategic position on the UK road network. Warehousing and distribution have taken over from manufacturing with major operators including Amazon, IKEA and Tesco and Lidl.

Low-rise housing, abundant green space and roads masked by trees feature in this view looking west across Nene Park. Image Credit: Rex Gibson

Cambourne

This is an outlier in time and location. It was started in the 1990s as a satellite of Cambridge. Its growth and direction have relied heavily on the major house building companies involved in the project. At times the new residents would have welcomed a development corporation to help ensure infrastructure and shared facilities kept pace with the growing population.

Cambourne is 9 miles west of Cambridge with the A1198, Ermine Street (the Old North Road), running along its western boundary. Its population had reached over 12,000 by 2021.

Image credit: Cambourne Town Council

Newton Aycliffe

Royal Ordnance Factory Aycliffe was established in 1941 as a vital but secretive part of the UK war effort. Employing up to 17,000 workers (many of them women) the factory operated for 4 years producing 700 million bullets and countless other munitions. It was located 15 miles west of the steel and chemical works of Teesside, close to railway lines – and of course the Great North Road.

The Royal Ordnance Factory, 1945. Image Credit – Google Earth

After the war it was decided to turn the factory into an industrial estate and establish a New Town for its workers. Lord Beveridge adopted the Newton Aycliffe as a flagship for his new welfare state, envisaging a “classless” town where manager and mechanic would live next door to each other in council houses.

Newton Aycliffe was to be “a paradise for housewives” with houses grouped around greens so children could play safely away from the roads. Beveridge opened the first house in November 1948 and the 1,000th in June 1953 (houses were painted pink and yellow to prevent the “new town blues”). A development corporation operated until 1988, in later years merged with that for nearby Peterlee.

The A1 continued to run along the eastern edge of the town until 1969 when the road was upgraded to motorway and re-routed a little further east.

The town has grown substantially and its economic fortunes have ebbed and flowed. Over the years Newton Aycliffe has (like other New Towns) come in for periodic taunts and ridicule. In 1957, The Daily Express writer Merrick Winn wrote about “The Town That Has No Heart”:

perfect planning and perfect monotony … nothing to do and nowhere to go…. twelve small shops, a few more half-built, and a keen, cold wind

Washington

Washington New Town came with a mixed inheritance. An ancient manor acquired in 1180 by a distant ancestor of the first president of the United States. And a legacy of centuries of coal mining which had created a unique culture and landscape.

Washington ‘F’ Pit Heaps, late 1950s. Image Credit: raggyspelk.co.uk

In the early 1960s, facing decline of the coal-mining and ship building industries, Durham County Council proposed a designation order under the 1946 New Towns Act to develop Washington as the region’s third New Town. The plan was for a town of 80,000 lying between Newcastle, Sunderland and Durham comprising 18 villages – some existing and some newly created.

The A1(M) forms the town’s western boundary. Its centre is 3 miles southeast of the Angel of the North. The A19 marks the eastern edge of Washington’s best-known industrial concern – the Nissan car manufacturing plant.

Durham House, Galleries Shopping Centre and Washington Highway, 1973. Image Credit: Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums

More Information about New Towns

Heritage English Garden Cities, English Heritage

The Town & Country Planning Association (TCPA)

Charlie in New Town – 1948 Government Information Film

Top of page image:

Charley in New Town – see video link above