Drovers and the Great North Road

The Great North Road has always been about conveying food as well as people, horses, trucks and freight. Until the mid-19th century much of that food would have been self-propelled; animals walking to market. The cattle, sheep, pigs, and poultry did not, of course, travel alone; there were many generations of drovers who guided, cajoled and cared for them as they made their final journeys.

They were often considered a nuisance by other road users, though they did not always travel exactly the same route. The drovers wanted to avoid any tolls and they wanted to maximise the opportunities to graze the “long acres” of verge. There are sections of the North Road where we can still follow drove roads running parallel to the primary route.

Hambleton Drove Road

Along the western edge of the North York Moors, the Hambleton Drove Road is now a 15-mile ribbon of white limestone track once used by the drovers on their way from Durham to York. Image Credit – Bruce Smith, www.localdroveroads.co.uk

Sewstern Lane

Close to the border of Lincolnshire and Rutland, Sewstern Lane runs from Long Bennington to Greetham. Image Credit – Bruce Smith

In “The Making of the English Landscape” W.G. Hoskins writes:

This road has a continuous history from the Bronze Age onwards. After it had been superseded in the seventeenth century by the Great North Road, which runs to the east of it through more inhabited country, Sewstern Lane became a recognised route by which cattle from Scotland and the North of England reached the Midland pastures and London: hence its later name of The Drift. Parts of it have been taken over for a secondary road, but much of it remains remote and quiet, rarely disturbed by a human voice.

Bullock Road

Bullock Road can be found between Wansford and Alconbury keeping to the higher ground to the west of Stilton and Sawtry. Image Credit – Rex Gibson

Some of the beasts were travelling quite short distances to markets in towns such as Stamford, York and St Ives. Others were trekking the length of the country from the northern hills to the greedy mouths of London. On reaching the capital, Smithfield market was a popular end point. It was conveniently located for the Great North Road, just outside the medieval city walls.

Many famous north road coaching inns feature on this website but there were also plenty of inns which focused on the droving trade. In 1830, the Red Lion near Royston (47th milestone on the old north road), advertised:

every accommodation may be had for drovers stopping on their way to town, any number of cattle can be taken in, during the whole of summer.

The practice of herding livestock long distances across the country has ancient origins. There is growing archaeological evidence for cattle being taken 4,000 years ago from as far away as Scotland to ceremonial feasting sites such as Woodhenge in Wiltshire.

About Drovers

Itinerant herdsmen living with their livestock were often seen to be amongst the lowest in society; filthy, rude, and often worse the wear for drink. There may be truth in this though it is clear that the occupation encompassed a wide range of roles and characters.

The more senior drovers (or topsmen) were in fact taking responsibility for valuable goods so the farmers and dealers involved in the trade needed to be able to trust them. They did not all sleep rough; there was a good network of inns attuned to the needs of the drovers and their animals.

One story is told of a farm auction where a shabby drover with ruddy face outbid all the local gentry, then proceeded to pay with money taken from his boots!

Historical images and accounts describe drovers of every age, temperament and capability.

one morning in July 1797 met on Chalk Hill (Northamptonshire) a boy, three feet high, fifteen years old. He had been to Smithfield with sheep. He went every week and had thirty miles to walk before nightfall. His frock (smock) was completely bound up and tied across his shoulders… turnpike tickets stuck in his hat band, noting the number of sheep paid for. The lash of his whip twisted round the handle which he converted into a walking stick.

Gentleman’s Magazine – Quoted in Bonser

He was a tall ungainly-looking man, in a Scotch cap, with the lower part of his face muffled up in plaid… A rudely-cast brass shamrock and thistle decorated the red and grey border of the woollen cap, in which was stuck a splendid eagle’s feather

Hillingdon Hall, Surtees, 1840s

They are required to know perfectly the drove-roads, which lie over the wildest tract of the country, and to avoid as much as possible the highways which distress the feet of the bullocks, and the turnpikes , which annoy the spirit of the drover. …. At night, the drovers usually sleep along with their cattle, let the weather be what it will; and many of these hardy men do not once rest under a roof during a journey from Lochaber to Lincolnshire.

A Highland drover was victualled for his long and toilsome journey with a few handfuls of oatmeal and one or two onions, renewed from time to time, and a ram’s horn filled with whisky, which he used regularly, but sparingly, every night and morning. His dirk, or skene-dhu so worn as to be concealed beneath the arm, or by the folds of the plaid, was his only weapon, excepting the cudgel with which he directed the movements of the cattle.

The Two Drovers, Walter Scott

Apparently, drovers often knitted stockings as they walked behind their beasts, and it is said that the Scottish drovers in particular would bleed their animals to provide blood to mix with oatmeal and onions to make a form of black pudding.

The long-distance drovers made epic trips. A single journey could take several weeks and often included a spectacular number of animals. One can imagine the deafening noise of bleating sheep and mooing cattle as the drover’s dogs chased and barked. Each day they would aim to travel 10 to 12 miles whilst maintaining the health and weight of their animals.

It was predominantly a male profession (as dictated by the early licencing system) but there are records of female drovers. For instance, the 1851 census records Mary Ann Smith from St Ives as a jobbing drover; Mary was a 44-year-old widow and head of household at 33 Sheepmarket.

Central to the Rural Economy & Growing Cities

The movement and trading of livestock have been important to the agricultural economy which was dominant for much of the past 1000 years in England, Wales and Scotland. With urbanisation and population growth there was increasing dependency on food brought from further afield.

The dominance of London from the early medieval period onwards, if not before, led to distant areas concentrating on cattle production to supply the capital with meat, leather and other animal products. Wales, the West Country and the north of England, predominantly regions with a long-standing pastoral economy, produced animals which were then walked overland to markets in the south.

Interpreting the Landscape, Michael Aston

The earliest references to droving appear in the 14th century. The “Diary of a Drover’s Month” describes the progress of a mixed herd of cattle and sheep in 1323 from Long Sutton (Lincs) to Tadcaster.

A letter of safe conduct is granted in 1359 to Scottish drovers, Andrew Moray and Alan Erskyn; they were to travel through England for a year with horses, oxen, cows and other goods and merchandise.

Many markets developed during the Middle Ages and livestock featured heavily. As well as the sale of livestock for butchery, animals were traded as they were moved to replenish herds, for fattening and even for export.

The general drift was from the pastures of the north and west to the population centres of the south and east. Bonser identifies a complex network of drove roads south from the Scotland and east from Wales.

Drovers’ routes from the Scottish Border. Image Credit – HJ Bonser

Defoe was familiar with the fairs held at both Northallerton and St Ives:

Besides their breeding of horses, they are also good grasiers over this whole country, and have a large, noble breed of oxen, as may be seen at North Allerton fairs, where there are an incredible quantity of them bought eight times every year, and brought southward as far as the fens in Lincolnshire, and the Isle of Ely, where, being but, as it were, half fat before, they are fed up to the grossness of fat which we see in London markets. The market whither these north country cattle are generally brought is to St. Ives, a town between Huntingdon and Cambridge, upon the River Ouse, and where there is a very great number of fat cattle every Monday.

In the 18th century geese and ducks from the Midlands and East Anglia were walked to Peterborough or St Ives, then sent twice weekly to London. Four-storey carts were introduced which according to Webb:

Ploughed their way through the mud with the best speed that two powerful horses could impart on them, travelling as much as a hundred miles in twenty-four hours

The Michaelmas Goose Fair in Nottingham was originally licensed in 1284. It came to last 21 days and at its peak 20,000 birds were brought there, apparently travelling at a rate of a mile and a half a day.

Although droving was an ancient economic activity, its peak was between 1700 and 1850, from the time towns and cities began to grow much faster until the coming of the railways. By the beginning of the 19th century it is estimated that some two million animals were moved each year.

Drovers and Crime

Like other travellers, drovers were vulnerable to crime. Responsible for large numbers of animals and sometimes carrying substantial sums of money they were an obvious target.

Whereas a drover of Kaber in Westmorland upon Tuesday, May 24th last, was robbed by two persons to him unknown, and had taken from him by them £144-7- at or near Ellerbecke in the hundred of Gilling West [the court recommends the inhabitants of the hundred] to repay the said sum without any further trouble.

Quarter Sessions at Northallerton

Conversely, farmers would be concerned that drovers might pocket the proceeds of their sales and find excuses as to why they returned empty handed. An Act of 1706 decreed that even if a drover was insolvent he was not allowed to be declared bankrupt.

Regulation of Drovers

Reflecting the growth of the droving trade, a system of licencing was introduced within the “Statutes at Large” enacted in the 16th century. A drover must be a married householder, at least 30 years old. The licence lasted for one year and contravention would incur a fine of five pounds.

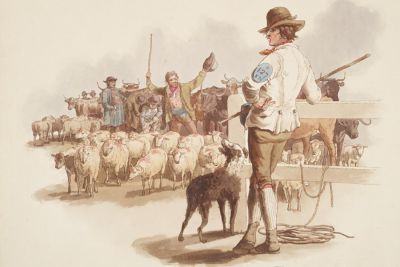

In the 1770s a London scheme gave rights and responsibilities to licenced drovers who were to have a uniform coat and numbered badge with the name of their principal (see image below).

The Smithfield Drover. Image Credit – Pyne’s Costumes of Great Britain, 1805

Drovers’ Dogs

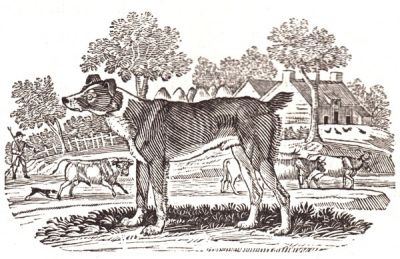

Admired for their intelligence and endurance the drovers’ dogs controlled large herds with minimal guidance. Breeds used included the cur, Smithfield collie (or coally), and corgis. Wolfhounds were sometimes used as guard dogs.

There are tales of dogs making their own way home, their masters having decided to extend their trips having completed the delivery of their livestock. A Welsh drover’s dog, Carlo, apparently returned alone from Kent to Wales, obtaining rest and refreshment at each of the inns previously visited.

The Cur or Drover’s Dog of Northumberland. Image Credit – Thomas Bewick’s General History of Quadrupeds, 1824

Shoes and Shoeing

Depending on the animal and the hardness of the surface it was not unusual to provide shoes for oxen and cattle. For instance there was a thriving shoeing industry at Wetherby through which 28,551 head of cattle passed in the year to August 1778.

Johnny Precious and other blacksmiths used to prepare for months in advance for these cattle. He also made shoes for pedigree cattle and when some were sent to America he supplied shoes for fixing before hey left the boat on their long walk to the ranch.

Whetherby, its People & Customs, Wardman

To protect the feet of geese they were driven through a compound of tar, sawdust and sand to form a protective pad.

Money and banks

The long-distance livestock trade presented financial challenges and risks which called for innovative solutions. Drovers might sometimes purchase cattle for cash but more often it was a question of trust.

In his “Rural economy of Norfolk” William Marshall paints an interesting picture:

This afternoon went to see the Smithfield drover pay off his “masters” at his chamber, at the angel, at Walsham. The room was full of “graziers” who had sent up bullocks last week and were come, today, to receive their accounts and money. What a trust! A man, perhaps, not worth a hundred pounds, brings down twelve or fifteen hundred, or perhaps two thousand pounds, to be distributed among twenty or thirty persons, who have no other security than his honesty for their money…but so it has been for a century past, and I do not learn that one breach has been committed. The business was conducted with great ease, regularity and dispatch. He had each man’s account, and a pair of saddle bags with the money and the bills, lying on the table…Having examined the salesman’s account the farmers received their money, drank a glass or two of liquor, and thrown down sixpence towards the reckoning, they severally returned into the market.

Some of the early regional banks had their origins in providing finance for the trade and in removing the need for drovers to carry large sums of cash. In 1799 a Welsh drover named David Jones established the Black Ox Bank at the King’s Head in Llandovery. It’s promissory notes (carrying the image of a black ox) could be exchanged at agents in London and elsewhere. The bank was eventually acquired by Lloyds Bank.

By the end of the 18th century the scale of the industry was impressive. About 100,000 cattle were driven from Scotland to England alone. The price per head varied greatly but was in the order of £5 to £6 and reached as much as £20 during the Napoleonic Wars. The cost of droving the length of the country (people, accommodation, tolls etc) could be in the order of a £1 per head.

As drovers sought to minimise their costs, they were at odds with the turnpikes of the 18th century; macadamised roads were bad for the animals’ hooves and the tolls were an extra burden – on top of the many existing charges for crossing rivers, entering towns and the like. By 1816 the toll on the Glasgow to Carlisle road was 1s 8d for every score of oxen or cattle.

Drovers and Smithfield Market

Great North Road drovers would have been heading to and from many different markets but Smithfield in London came to surpass all others.

Bird’s Eye View of Smithfield Market, Pugin and Rowlandson, 1811

Origins & Location

Smeeth Feld described the flat open area east of the River Fleet just before the roads from the north reached the city walls of London. In medieval times there was a concentration of nearby religious institutions including St Bartholomew’s Priory (founded 1123), and the St Mary’s Clerkenwell nunnery ( c1144).

Map of London c1520 Image Credit – www.layersoflondon.org

A horse and livestock market was being held there by the 12th century.

There is also, without one of the city gates, and even in the very suburbs, a certain plain field, such both in reality and name. Here, every Friday, unless it should happen to be one of the more solemn festivals, there is a celebrated rendezvous of fine horses brought thither to be sold. Thither come, either to look or to buy, a great number of persons resident in the city, Earls, Barons, Knights, and a swarm of citizens.

… in another quarter, and apart from the rest, are placed goods of the peasant, implements of husbandry in all kinds, swine with their deep flanks, and cows with their distended udders. Oxen of bulk immense; the woolly tribe.

Descriptio Nobilissimi Civitatis Londoniae , William Fitz-Stephen, 1174

The area became well known as the site of gallows, and the annual Bart’s Fair.

From Smithfield the animals destined for slaughter were taken a short distance within the city walls to the Newgate Shambles, or to Eastcheap, a market in the east of the city.

Butchery not confined to animals

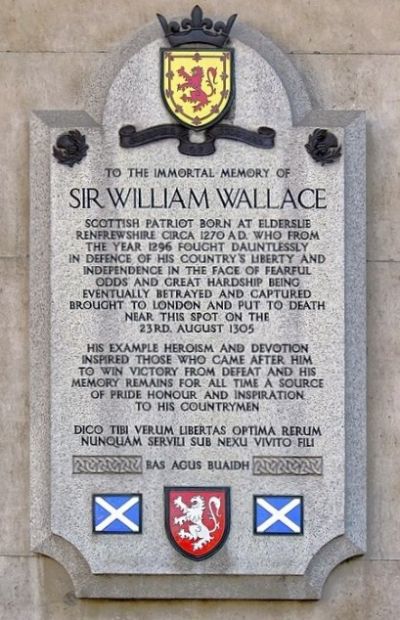

Amongst the high-profile heretics and traitors whose days ended at Smithfield was William Wallace. Having inflicted humiliating defeats on the English as Edward I sought to seize control of Scotland, Wallace was eventually betrayed. He was rushed down the Great North Road in 1305. After his trial at Westminster he was hanged at Smithfield then “emasculated” and eviscerated whilst still alive: his limbs were despatched back to Scotland as a reminder to other rebels; his head was tarred and displayed on a spike on London Bridge. His execution coincided with the summer fair adding heightened excitement and entertainment for the revellers.

William Wallace Memorial, Smithfield, London. Image Credit – Acabashi, CC-BY-SA 4.0

Less than a century later it was, peasant agitator, Wat Tyler’s turn to be taught a lesson at Smithfield. Ensuring that the 14-year-old King Richard II would not be persuaded to concede to the populace, Tyler was struck by the London Mayor, William Walworth. The injured man was later beheaded.

The tradition continued. During reign of Queen Mary I in the 16th century, protestant men and women were burnt to death at Smithfield as punishment for their religious beliefs.

Death of Wat Tyler. Image Credit Jean Froissart, Chroniques, British Library

The Bartholomew Fair

The fair started in 1133 as a market for buyers and sellers of cloth. Over the next 700 years the food, drink and entertainments became the main attraction. By 1600 it was a two-week festival with puppet shows, wrestlers, a big-wheel, dancing bears and contortionists.

Urban expansion, redevelopment and the demise of the cattle market meant it came to an end in 1855.

Livestock on a vast scale

By the mid-18th century Smithfield was processing 75,000 cattle and 500,000 sheep each year and their number would treble during the next hundred years. Whilst serving an important function this activity was not appropriate for what had become an inner-city area by the 19th century. Dickens describes Smithfield in his novel Oliver Twist, published 1837–1839:

The ground was covered, nearly ankle-deep, with filth and mire; a thick steam, perpetually rising from the reeking bodies of the cattle, and mingling with the fog, which seemed to rest upon the chimney-tops, hung heavily above.

Countrymen, butchers, drovers, hawkers, boys, thieves, idlers, and vagabonds of every low grade, were mingled together in a mass; the whistling of drovers, the barking of dogs, the bellowing and plunging of oxen, the bleating of sheep, the grunting and squeaking of pigs, the cries of hawkers, the shouts, oaths, and quarrelling on all sides; the ringing of bells and roar of voices, that issued from every public-house; the crowding, pushing, driving, beating, whooping, and yelling; the hideous and discordant din that resounded from every corner of the market; and the unwashed, unshaven, squalid, and dirty figures constantly running to and fro, and bursting in and out of the throng; rendered it a stunning and bewildering scene, which quite confounded the senses.

The arrival of the railways also had a dramatic impact on the need to bring live animals to the capital for slaughter. In 1855 a new livestock market and slaughterhouses were opened in Islington, replacing Smithfield and the Newgate Shambles.

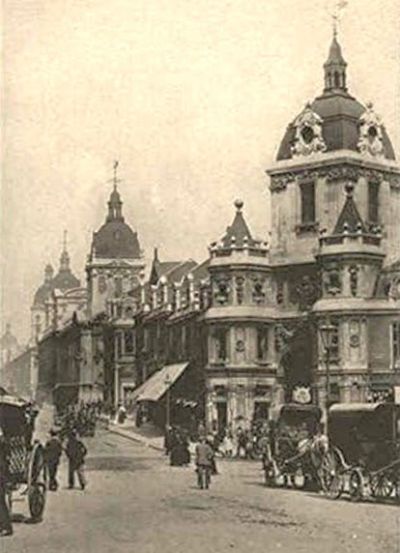

The fine Victorian building at Farringdon which we know as Smithfield was the work of Sir Horace Jones. It was constructed over a period of 25 years and eventually housed the city’s main fish and vegetable markets as well as that for meat. This in turn is now being displaced and the building will instead become home to the London Museum.

Smithfield Meat Market, Postcard c1900

More Information about Drovers

The Drovers, K J Bonner, 1972

Local Drove Road Website – Bruce Smith

A Social History of St Ives & its People

Image at top of page: Returning from Market, Image Credit – John MacPherson