The Gough Map and the Great North Road

Early maps of the Great North Road are scarce. Historians such as Margary have pieced together a fairly reliable network of Roman Roads which includes what we know as Ermine Street and Dere Street. In 1675 Ogilby launched the modern generations of road maps with his Britannia. The so-called Gough map of the late 14th (or early 15th) century is a unique step in between.

Unfortunately there is much about the Gough map which is ambiguous. While it features many towns and cities across England it is less than certain that it aimed to document routes between them. There are a series of red lines between some of the towns including distances in roman numerals – but they are somewhat inconsistent and their significance less than clear.

The route north from London as defined by these red lines passes through Hertford, Royston, Huntingdon, Stamford, Newark, and Doncaster. [A more easterly route via Stony Stratford, Northampton and Leicester to Grantham is also shown.] Further north the route highlighted is Tadcaster, Leeming, Bowes, Brough and Penrith to Carlisle. Hadrian’s Wall is represented pictorially and whilst Scottish towns are shown there are no Scottish “red lines”.

Image at top of page: Gough Map annotated with modern place names. Credit – The Gough Map Website – Linda Godden

About the Gough Map

What is the Gough Map?

It is the earliest surviving map to show settlements, rivers and routes across Britain and to depict a recognisable coastline.

The map is oriented towards the east. Over 600 towns and cities are represented by vignettes – a building, church, castle or small group of buildings with red roofs. It is drawn on two pieces of sheepskin parchment and measures approximately 550mm by 1200mm.

Rivers and their watersheds feature strongly: roads rather less so, though thin red lines between some of the towns appear to represent major routes.

Why is it called the Gough Map?

The map is named after the antiquary Richard Gough who bought it for half-a-crown in 1774 at the sale of the collection of Thomas Martin of Palgrave (it was described as “a curious and most ancient map of Great Britain”).

Gough bequeathed the map to the Bodleian Library, Oxford, in 1809.

Richard Gough, Director of the Society of Antiquaries 1771-1791. Image Credit – John Downman [Verification of these details would be appreciated]

How old is the Gough Map

The precise date of the Gough Map is not known.

The map depicts a city wall around Coventry which was not built until 1355 so it was definitely drawn later than that. Many estimates steer towards the last 25 years of the 14th century though others suggest it was subject to updating and refinement into the early 15th century.

Equally unclear is just who was responsible for the map. Given the breadth of knowledge condensed into the map, and the investment required to produce it, the likelihood is that it was commissioned by central government.

How accurate is the Gough Map?

The easy answer is that the Gough Map is far more accurate than any previous maps.

The more nuanced answer is that it depends where you look. The broad outline of the country is recognisable though not to consistent scale with, for instance, Scotland narrowed down and islands such as Anglesey and Orkney magnified. The width of rivers is exaggerated (perhaps reflecting their importance to Medieval travellers). The density of towns and the accuracy of their positioning is greater in certain locations (such as the East Midlands and South East) prompting some to speculate that was where the main contributors lived.

What are the red lines?

The thin, straight red lines drawn between many of the towns appear to suggest longer routes or roads. Nearly all are accompanied by a number in Roman numerals representing distance measured in leuga (about 10 furlongs).

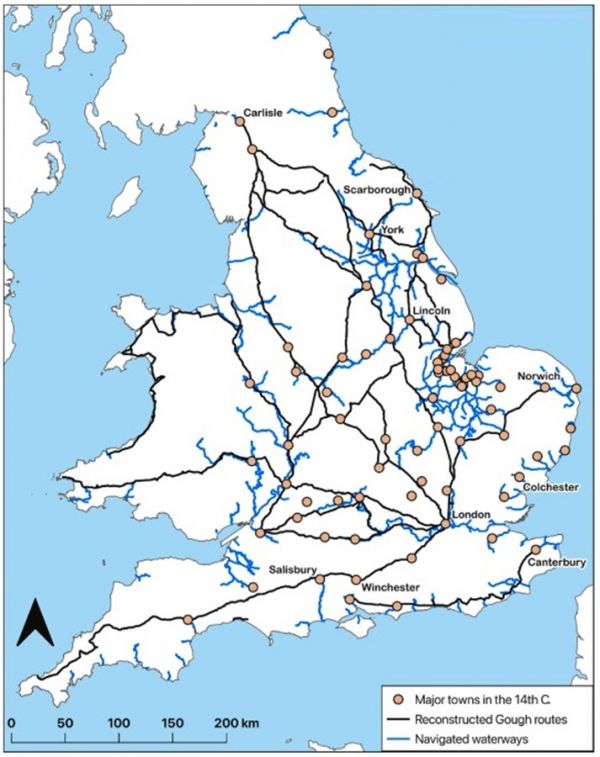

They are not defined as longer distance roads though they can (in part) be characterised as 5 routes radiating from London, and another that connects important towns along the south coast from Canterbury to Southampton. There are some notable omissions which are hard to fathom; for instance, there is no line shown between London and Dover, and none between York and Durham. There are some areas where significant towns are not accessed by red line; for instance Kings Lynn and other Fenland towns, perhaps because at that time it was the river network which provided the more significant connections.

A reconstruction of the roads of the Gough Map combined with known navigated inland waterways and large urban/commercial centres in the 14th century. Image Credit – Oksanen and Brookes

Conservation & Research

The Gough Map has attracted academic analysis and interpretation for many centuries. Notable projects during the 21st century include a major conservation project by the Bodleian Library which both restored the integrity of the map and provided insights into its production. Other work has focused on digitising the map to enable far more effective comparison with other historic and archaeological information using GIS (Geographic Information System) technologies.

Medieval Roads – 400 to 1400

A thousand years of the evolution of England’s roads is largely unrecorded. We know that many Roman routes were followed over the subsequent centuries but some were not; and changes in regional power structures and economies caused some routes to fade and others to strengthen.

The GIS research project by Oksanen and Brookes on “The afterlife of Roman roads in England” compares the “roads” implied by the Gough Map with the Roman network inferred by Margary and others. The correspondence of primary routes is obvious and even when using highly objective criteria the researchers can attribute at least 35% of the Gough roads to the Roman period (or earlier).

the survival of Roman roads depended greatly on the afterlives of specific places. For example, near medieval towns such as London, Leicester and Winchester, which occupied the same locations as their Roman predecessors, there is good correspondence between the routes depicted on the Gough Map and earlier Roman roads. By contrast, routes near former Roman towns such as Sorviodunum, beside Old Sarum in Wiltshire and Venta Icenorum, Caistor St Edmund in Norfolk, that were replaced by new towns at Salisbury and Norwich respectively, survive only partially in the modern landscape and do not feature in the Gough Map. For all stretches of Roman roads, survival depended on an interplay between broader macro-processes and particular local situations that were unique to each.

The Roman Roads of Britain – itiner-e interactive map

A New Road Map of England & Wales c 1450 to 1500

David Harrison has taken the Gough Map and combined it with other data to draw a compositee Medieval map of the primary roads of England and Wales. Harrison has previously demonstrated the major investment in the roads and bridges of Britain from as early as the 10th century. He is firmly of the view that the red lines of the Gough map are consistent with references to “highways” and “king’s ways” in other sources. Highways became metalled with gravel, sand and stone, and raised above the surrounding land where necessary.

Another indication of the significance of long-distance highways comes from the 15th century Wars of the Roses. Edward IV’s army defeated the south bound Lancastrians in a bloody battle at Ferrybridge, while the contest at Losecoat Field was also close to the Great North Road (near Stamford). The Battles of Barnet and St Albans took place close to the Chester Road.

The Medieval Roads & Bridges of England. Image Credit – Giles Drake / David Harrison

More Information about the Gough Map

The Gough Map Website – Linda Godden

The afterlife of Roman roads in England, Oksanen & Brookes

Medieval Travel – Essays from the 2021 Harlaxton Symposium:

The Roads of Medieval England, David Harrison

Historic Ways – Road Map of England & Wales in the Late Middle Ages