Forster and the Great North Road

The area close to Forster’s childhood home, Rooks Nest, has become known as Forster Country by those seeking to deter the expansion of Stevenage across the only remaining farmland within the borough. The rolling farmland is punctuated by hedgerows and small woods. The chalk hills stretch north east towards Baldock and Royston, overlooking the route of the Great North Road.

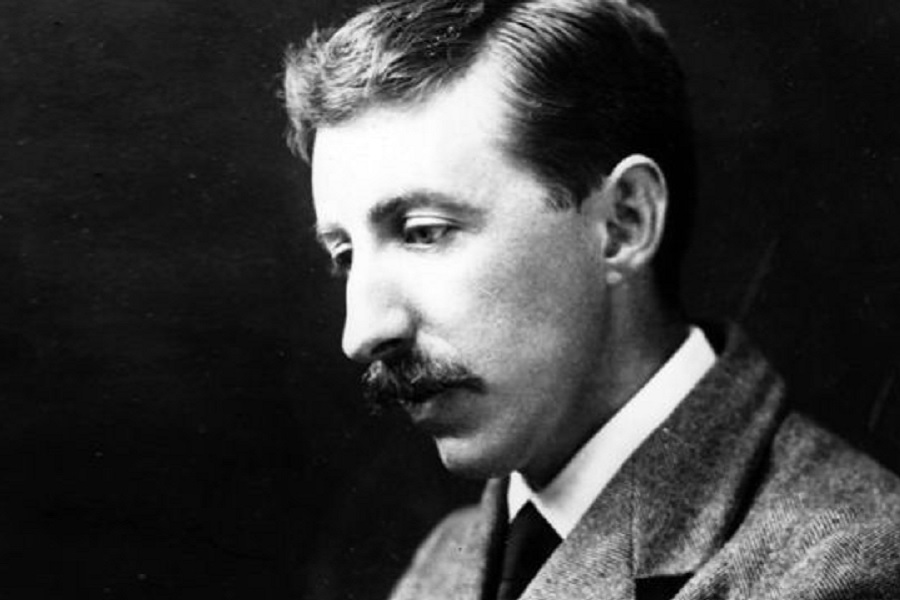

About Forster

The writer Edward Morgan Forster lived at Rooks Nest House near Stevenage between the ages of 4 and 14. His time there had a lasting impact on him. In later life he often returned to Rooks Nest as the guest of composer Elizabeth Poston.

Rooks Nest became “Howards End” in his most famous novel, reflecting on class differences, emotions, and communication in early 20th century England.

Edward Morgan Forster (always known as Morgan) was born in 1879 into a wealthy Victorian family. His father, an architect, died when he was a small infant and his mother Lily brought her son to live in the Hertfordshire country in 1883. Part sixteenth-century, Rooks Nest (then Rooksnest) is a small farmstead near to St Nicholas Church on the northern outskirts of Stevenage.

Howards End, was published in 1910 when the Forsters had moved to Weybridge. It was his fourth novel and brought Forster success and recognition as a writer. It was followed by Passage to India in 1924. His final novel, Maurice, a homosexual love story was published posthumously in 1971.

In “Notes on the English Character” in 1920, Forster reflects on the repressed emotions of the time:

‘The trouble is that the English nature is not at all easy to understand. It has a great air of simplicity, it advertises itself as simple, but the more we consider it, the greater the problems we shall encounter. People talk of the mysterious East, but the West also is mysterious. It has depths that do not reveal themselves at the first gaze. We know what the sea looks like from a distance: it is of one colour, and level, and obviously cannot contain such creatures as fish. But if we look into the sea over the edge of a boat, we see a dozen colours, and depth below depth, and fish swimming in the sea. That sea is the English character – apparently imperturbable and even. The depths and the colours are the English romanticism and the English sensitiveness. We do not expect to find such things, but they exist. And – to continue my metaphor – the fish are the English emotions, which are always trying to get up to the surface, but don’t quite know how. For the most part we see them moving far below, distorted and obscure. Now and then they succeed and we exclaim, “Why, the Englishman has emotions. He actually can feel!” And occasionally we see that beautiful creature the flying fish, which rises out of the water altogether into the air and the sunlight. English literature is a flying fish. It is a sample of the life that goes on day after day beneath the surface; it is a proof that beauty and emotion exist in the salt, inhospitable sea.’

When Stevenage New Town was first planned in the late 1940s, Forster campaigned to save the same countryside from development. In a 1946 radio broadcast he remarked:

‘I was brought up as a boy in a district which I still think the loveliest in England…hedges full of clematis, primroses, bluebells, dog roses and nuts.’

He was unhappy with the development of Stevenage new town, which he felt would ‘fall out of the blue sky like a meteorite upon the ancient and delicate scenery of Hertfordshire’.